“I’m a lazy motherfucker. In fact, I’m looking for a place to lay down right now. I’m the type of motherfucker who’ll go to your house, smoke your pot, eat your chicken, borrow twenty dollars from ya—I do that shit a lot of the time on purpose just to get all the wide-eyed awe out of the way.” Thus declared P-Funk maestro and 1997 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductee George Clinton in “The Goduncle,” an essay I put together decades ago along with new pieces about the equally titanic Al Green and Neil Young to close out my 1998 Harvard anthology Grown Up All Wrong, which I reprint in full below as this month’s Big Lookback. I’ve never forgotten that quote (from a Steven Blush interview in a long-gone magazine called Seconds), because in my view, Clinton was and remains a great artist—so prolific and so original that more than even Green or Young he comes trailing a flock of heirs if not disciples whose debt to him is candid and unmistakable even if they hate his guts, as some may have reason to.

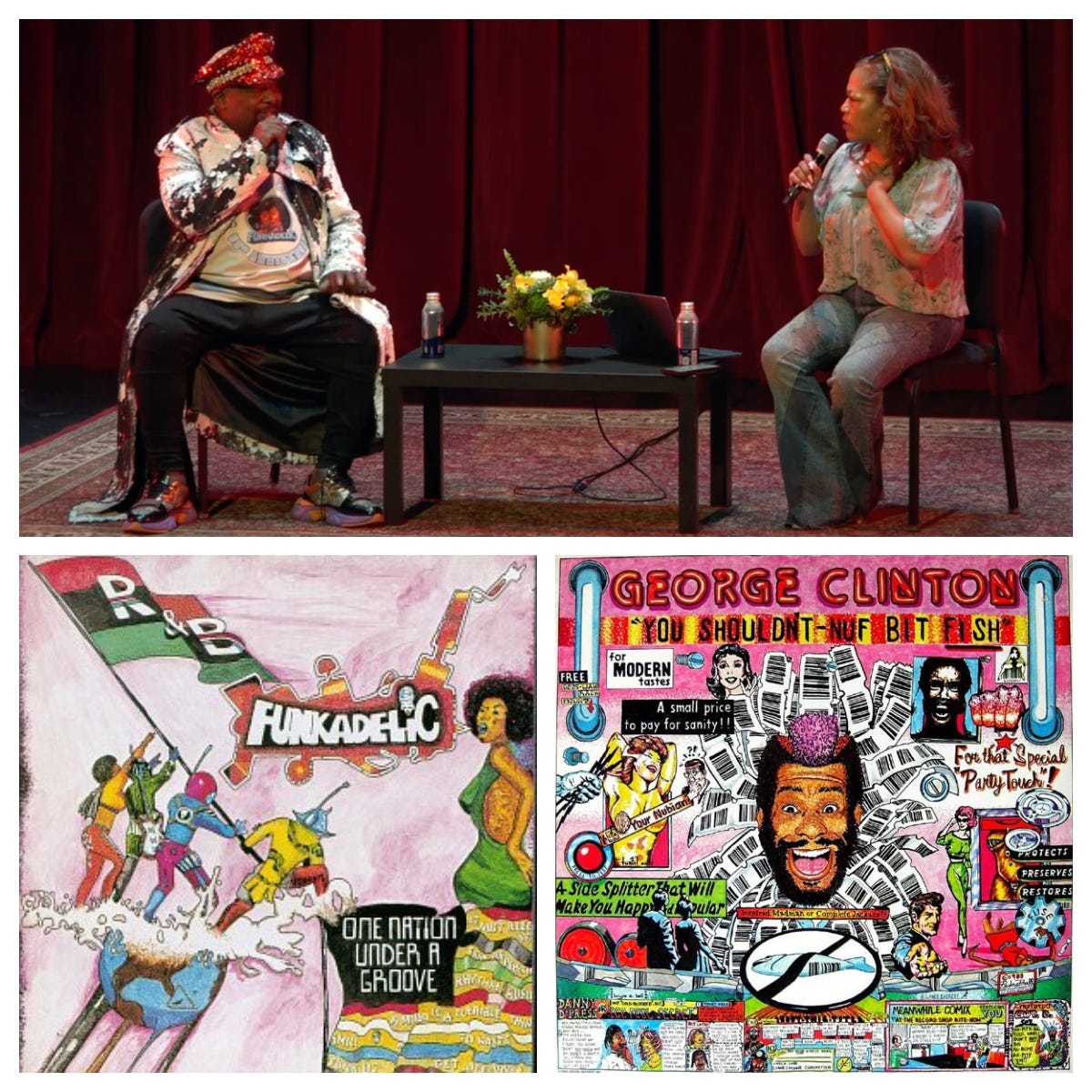

I bring this up because for me one of the most memorable moments of Legacy! Music Collections and Archives, the March USC PopCon that spurred me to finally confront the messy question of what will become of the countless sound recordings (and books, damn it, books) I’ve accumulated since I became a rock critic in 1967, was a one-on-one between longtime music journo Danyel Smith and Clinton, whose career flowered roughly between 1975 and 1995 and ain’t necessarily over yet. Clinton’s 23-track 2018 album Medicated Fraud Dogg, credited to Parliament, as one branch of his P-Funk conglomerate started billing itself on 1970’s Osmium, begins with a grim ditty about sleeping in the hallway called “Medicated Creep” and ends with a happier one about “living with the right to be wrong” called “Type Two.” Neither pick hit nor must to avoid, it’s solid work for an 82-year-old, to which I’d add “like me” if I had much else in common with George Clinton beyond admiring if not adoring his music—and also, I suppose, if he hadn’t been a mere 76 when he put it together, apparently some time after he ended a 40-year addiction to crack.

Insofar as these things can be pinned down, the addiction is pretty much a matter of record, although if Smith even hinted at it I missed the reference. It’s also pretty well established that during P-Funk’s long if incoherent heyday Clinton not only plied his ever-shifting band cf sidemen with illegal substances but took the retail value of those substances out of their paychecks. Genius, absolutely; saint, far from it. Yet one of the most striking aspects of this conversation was how warmly and indeed unstintingly Clinton praised an ever-shifting band that included such well-remembered titans as Bootsy Collins and Bernie Worrell. Often, he acknowledged, sidemen came and went; in one tale, some white kid crashed the studio, played great for 15 minutes, and disappeared without leaving his contact info or even his name. He told us that P-Funk was inspired by Pink Floyd, Sun Ra, and especially—once they’d emigrated from Plainfield, New Jersey, to Detroit, Michigan—Motown. He told us that Eddie Hazel’s legendary guitar solo on “Maggot Brain” (which I suggest you seek out posthaste) followed Clinton’s instruction to pretend his mother had died. He told us he spends time on TikTok, which he unequivocally favors, with grandkids who tell him he’s a “cool old dude,” but that if the “sample-dis-and-sample-dat” laptop approach is “workin’ then there’s somethin’ I’m missin’.” Instead, he told us, he “advocates for music in the schools.” He told us that he thanks modern medicine that he’s no longer on crack. He didn’t tell us that in June he’ll turn 83. Never seemed to occur to him.

It’s a tribute to George Clinton’s genius that it took him forty years in the music business—the Parliaments got together in 1955, when Clinton was fifteen, twelve years before “I Wanna Testify” became the first of his four-count-’em-four top-forty hits—to get into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. To be honest, I’m still a little surprised he made it at all. He can’t sing, he can’t play, and he’s not truly a songwriter, because his songs (not to mention his “songs”) rarely make sense out of context, although as hip hop testifies, his jams sure do. Equally discomfiting for would-be canonizers, he’s more than a nonrelic. Nonrelics you can deal with, and there are loads of them; Uncle Mick’s 1993 Wandering Spirit is arguably a better record than Uncle Jam’s 1993 Hey Man . . . Smell My Finger, not to mention his 1996 T.A.P.A.F.A.O.M., credited in the wake of Parliament-Funkadelic’s belated canonization to not just George Clinton but George Clinton and the P-Funk Allstars.

The difference is that Clinton never matured. Evolved, yes; became an elder, definitely; matured, no. Although it’s odd to picture in the author of “No Head No Backstage Pass,” and silly to make too much of, he seems to have remained with the same woman throughout the P-Funk period, and several of the kids he fathered by his first (and different) wife eventually helped him take it to the stage. But that cuts both ways—a fat lot of stability his domesticity signified back when he was gobbling LSD and dedicating his art to the Process Church of the Final Judgment. He remains a loose cannon—an outrageous, eccentric, visionary crank. Check the interview in Seconds where he forswore hip hop solidarity by dissing the world’s most famous rapist—“Tyson had that Bronx ‘Yo, bitch’ mentality”—and then went on (for quite a while) about Charlie Manson being down with the Mafia. At the end, he summed up his own contribution to humanity: “I’m a lazy motherfucker. In fact, I’m looking for a place to lay down right now. You know, I know how to get away with shit. I’m the type of motherfucker who’ll go to your house, smoke your pot, eat your chicken, borrow twenty dollars from ya—I do that shit a lot of the time on purpose just to get all that wide-eyed awe out of the way.”

In other words, canonizers have Clinton’s go-ahead to dismiss him as a con man—a self-promoting svengali with a good band under his thumb. He himself told Seconds that the reason P-Funk albums wear so well is that they have Eddie Hazel and Bernie Worrell and the rest soloing all over them. But that’s just George, greasing the wheels as usual. Spinoffs from Hazel’s Games, Dames and Guitar Thangs to Worrell’s Blacktronic Science go to show that Dr. Funkenstein—with essential conceptual help only from Bootsy Collins—is the artist, the others his material. Wheeler-dealing entrepreneur, harmonizer turned ace producer-arranger, r&b interlocutor as first rapper in the known universe—if any entertainer ever crossed the American huckster with the African trickster, it’s George Clinton.

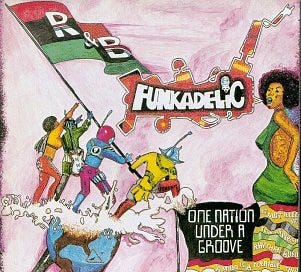

As this job description suggests, Clinton hasn’t devoted much energy to smoothing out his resume. In 1979-1980, for instance, a band that might as well have been called P-Funk released seven albums on Warner Bros., Casablanca, and Atlantic under the names Parliament, Funkadelic, Bootsy’s Rubber Band, Bootsy, Parlet, and the Brides of Funkenstein. Beset by fatigue, jealousy, and fiscal discontent, the Mothership was going the way of all communes by then, and while Clinton had produced definitive music in disco’s teeth—Mothership Connection (1976), Hardcore Jollies (1976), Funkentelechy Vs. the Placebo Syndrome (1977), One Nation Under a Groove (1978), and Motor-Booty Affair (1978), to stick to the prime stuff—he was having trouble positioning himself commercially, so most of these records are far from great. But as with Westbound-era Funkadelic, which takes some six albums to get its shit together, all of them are vehicles for memorable music, just like every other record he’s ever put in gear.

It’s another mark of his genius that his output doesn’t compile comfortably past its own inconsistencies. PolyGram, always the most effective of his labels in the basic matter of keeping his oeuvre out there, naturally chose to make a two-CD set called Tear the Roof Off 1974-1980 the flagship of its Funk Essentials series in 1993, and I played it with pleasure that entire summer. Because it isn’t confined to radio edits and lasts two-and-a-half hours, it’s less hyper than 1984’s superb but disorienting serial orgasm, Parliament’s Greatest Hits, which hit me when it appeared as a serial orgasm. And since Parliament was conceived as the pop band, two CDs worth of catchy riffs and chants are there for the sequencing. But when I go back to the originals, I find myself loving the playlets, the slow stuff, the jive—like Funkentelechy’s “Sir Nose D’Voidoffunk” and “Wizard of Finance,” or “Rumpofsteelskin,” which fills out the endlessly entertaining first side of Motor-Booty Affair. It’s the same with Go fer Your Funk and “P” Is the Funk, the two often ear-opening, always ex post facto outtakes collections Clinton put out himself on AEM from P-F HQ in Eastpointe, MI. And it applies as well to Music for Your Mother, two CDs of completist triumph comprising the A and B sides of every Westbound forty-five Funkadelic ever released. The fifteen nonalbum tracks, including even the filler instrumentals, are far from d’void. But the albums are full of funk, full of meaning, full of shit.

Just because Funkadelic and Parliament were the same doesn’t mean they weren’t different. The standard analysis distinguishes Funkadelic’s heavy rock from Parliament’s light funk, but from here it sounds to me like Funkadelic was the ghetto band. Forget “Papa Was a Rolling Stone” and Isaac Hayes and the rest of that velour. No music better evokes the bombed-out hopes of the black-power young in the early seventies—the druggy utopian fantasies that fuel the despair of Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song and John Edgar Wideman’s Homewood novels—than the Westbound albums. The most consistent are Standing on the Verge of Getting It On and Let’s Take It to the Stage, but listening now, it’s not hard to hear why Free Your Mind and Your Ass Will Follow—the first time Clinton was given the run of a studio, twenty-four acid-demented hours as thirty acid-demented minutes—is a cult fave in slackerland. Not only is the shit weird, the weirdness signifies. From the educational “Jimmy’s Got a Little Bit of Bitch in Him” to the devotional “Cosmic Slop,” Music for Your Mother is merely the cream.

Whether the secret is musical development, changing patterns of substance absorption, or enough money to go around, the Warners Funkadelic albums are sunnier, more rousing and communal—especially if you choose to view “The Doo Doo Chasers” as a jolly Jim Jones parody and the manically depressive Electric Spanking of War Babies as some combination of label kissoff and There’s a Riot Goin’ On (with Sly pitching in). And immediately following that came Computer Games, his first “solo” album for Capitol and without question the most spiritually complete record he’s ever made. It’s got jams—“Get Dressed” vies with the now obviously definitive “Atomic Dog” itself. It’s got intimations of romantic responsibility from an old dog unlikely to be remembered for his love advice. But what’s most noticeable in retrospect is how easily Clinton relates to the twin teen cultures of the time, rap and videogames. He’s not just indulgent, he makes them his own, in an avuncular but far from uncritical way. No other nonrelic can make such a claim.

All that said, it must be added that in the years since Computer Games—which followed the first Funkadelic albums by only twelve years, after all—Clinton has slowed down. The first half (formerly side) of the Computer Games follow-up You Shouldn’t-Nuf Bit Fish is so much fun it could change your philosophy, and don’t think for a minute that 1989’s Cinderella Theory or 1993’s Hey Man . . . are more mortal than such B jams from the seventies as Trombipulation and Uncle Jam Wants You. But note that the man who was once an ever-flowing fountain of funk has released only four new albums since 1986. In later years his major source of currency both historical and monetary has been sampling, which he was Dutch uncle enough to find cool long before it was worth two cents a record and fifty per cent of the publishing. As of 1993, which due to his popularity with the West Coast gin-and-juice set was a kind of heyday for him, he’d already cut some three hundred such deals, more than JB himself. Moreover, he was unlike JB in one crucial respect: hip hoppers always respected his moral vision as well as his beats. And in typical get-away-with-shit fashion, Clinton happily exploited this well-earned honor for meaning and profit.

Behind JB in the godfather sweepstakes when he cut The Cinderella Theory in 1989, he extracted cameos from Flav and Chuck while adjusting his Paisley Park debut to the electro style of his label head, one of the few pretenders he never accused of faking the funk—where race men unsure of their manhood assumed the supposed worst about the flamboyant little Twin Cities mulatto, the benevolent Uncle Jam didn’t care how much bitch Prince had in him as long as his beats warped and woofed. On Hey Man . . . Smell My Finger, horn charts and nonsense syllables were primed for rental while guest shots from Chuck, Flav, Ice Cube, Dr. Dre, Humpty Hump, Yo Yo, Kam, and MC Breed evoked straight-up hip hop. And speaking of moral vision, the youngbloods’ gratuitously tough talk and wishfully literal protests pointed up whose mind was free and whose wasn’t—even if Clinton couldn’t resist the self-praise that was funny when Trick James posed a threat but seemed like rap cliches after hip hop had proved him as large as he thought he was. Then, changing labels yet again just as black music was rediscovering the comforts of r&b proper, he declared it exactly the moment to construct his most luxurious groove album ever. So on T.A.P.A.F.A.O.M., smooth high-register choruses male and female body-surfed along on buoyant booty-bump bass lines as Clinton and associates rapped and/or sang about the beach and the Cherokee trunk without disrespecting the mirrored boudoir or the overstuffed layaway couch.

None of the late records certifies his nonrelic status or fully reinforces our longing for Clinton’s impact to remain cultural as well as musical. Only a hit could do that, preferably a monster untainted by novelty, which seems a cruel demand to place on the man who lit up the phones with “Flashlight” and made a star of Mr. Wiggles the Worm. No “My Ding-a-Ling” for this name brand—he needs his own “Rockin’ in the Free World,” which I hereby nominate as P-Funk’s first cover version ever (b/w Sun Ra’s “Rocket #9”). Nevertheless, the evolution of these barely diminished albums bespeaks not commercial expediency but a responsiveness that can only make one wonder what George Clinton thinks of Tricky and the Chemical Brothers. And if one wonders hard enough, one may conclude that one has a couple of clues.

One Nation Under a Groove’s scandalously scatalogical “Promentalshitbackwashpsychosis Enema Squad (The Doo Doo Chasers)” isn't actually a Jim Jones parody, I don’t think, although it was sure timed right and does ape true believers in the throes of the call-and-response so oft extolled in utopian accounts of the African-American tradition Jones perverted. “The world is a toll-free toilet,” Clinton intones, and the band comes right back at him with a ragtag “The world is a toll-free toilet.” “Our mouths neurological assholes,” Clinton continues, and once again the congregation recites. And so it goes, through Tidy Bowls and music to get your shit together and meburgers and lunch meat and holy shit, half shock comedy and half postcountercultural ridicule of the ego and the intellect and the decay of the word. The humor lends a depth thus far unknown to Tricky’s morbid maunderings, and the message conveys its own wildly burlesqued hope of redemption, but the darkness of the historical analysis is ahead of its time, and so, significantly, is the murkiness of the textures, in which falsetto doowop harmonizers obscure phrases like “in a state of constipated notion” and Peter Lorre can be overheard asking, “Which one is George Clinton?” That’s easy—he’s the one with the stinky diaper. And if anybody ever hires him for a trip hop record, “The Doo Doo Chasers” is ripe for remix—as squishy as old Limburger.

As for chemical brotherhood, refer to Capitol’s Greatest Funkin’ Hits, a 1996 remix album that avoids the promotional overkill and commercial double jeopardy of its half-assed demigenre. The live track, the previously unreleased, the woofing bookends, the recycled P-Funk show-stoppers, the remakes from George C.’s unnoteworthy 1986 R&B Skeletons in the Closet and Jimmy G.’s unnoticed 1985 Federation of Tackheads (featuring, one is told, Clinton’s wayward kid brother)—all are conceived as atomically mongrel antidotes to what the funkateering annotator-illustrator Pedro Bell labels “the flunkmare of wooferless pop musik.” Commercially it’s a slightly dated hip hop exploitation, with new interpolations from Coolio, Ice Cube, and Humpty Hump, and musically it’s sex-various but also heartbeat-deep, which Clinton has always told us is the way any good sex must be. In short, it’s not uncorny. The oldest mix on the record, however, is the previously uncollected twelve-inch of “Atomic Dog,” which I hadn’t heard as such since the middle eighties. And in the sonics of its hyped-up synth-bass I could easily discern arena-techno’s block-rockin’ beats. One can only look forward to Clinton’s excursions into drum ‘n’ bass, conning who knows what skinny London boy with digital smarts.

The best of all possible worlds, at least in this dystopian century, will have the heart to give it up to the Goduncle for as long as he shall slam. Maybe we don’t need him, but for sure we can use him. Fried ice cream remains a reality, and somebody has to stand up and shout about it.