I Have to Deal With It, It Is the Legacy

A paper from the recent PopCon at the USC Thornton School of Music in Los Angeles

I warned last week that even in the wake of the 2012 giglog trifecta I posted in lieu of the Consumer Guide while I attended this year’s PopCon in L.A., said CG might be further delayed, and so indeed it has proven to be. The culprit is the worst cold I’ve had in years—stuffed nose, slight fever, Covid test clean (so far??), flying home an exhausting chore. So instead I thought I’d publish the PopCon lecture I delivered this past Saturday, in which I exploited the conference’s announced theme of “archives” to finally get my teeth into a project I’ve been putting off for years: figuring out what’s to become of my stuff after I die. Assuming I’m not fatally ill at the moment, all my findings are preliminary but also as head‑clearing as I can expect given the current state of my head.

CG sometime next week, I very much expect and hope even more.

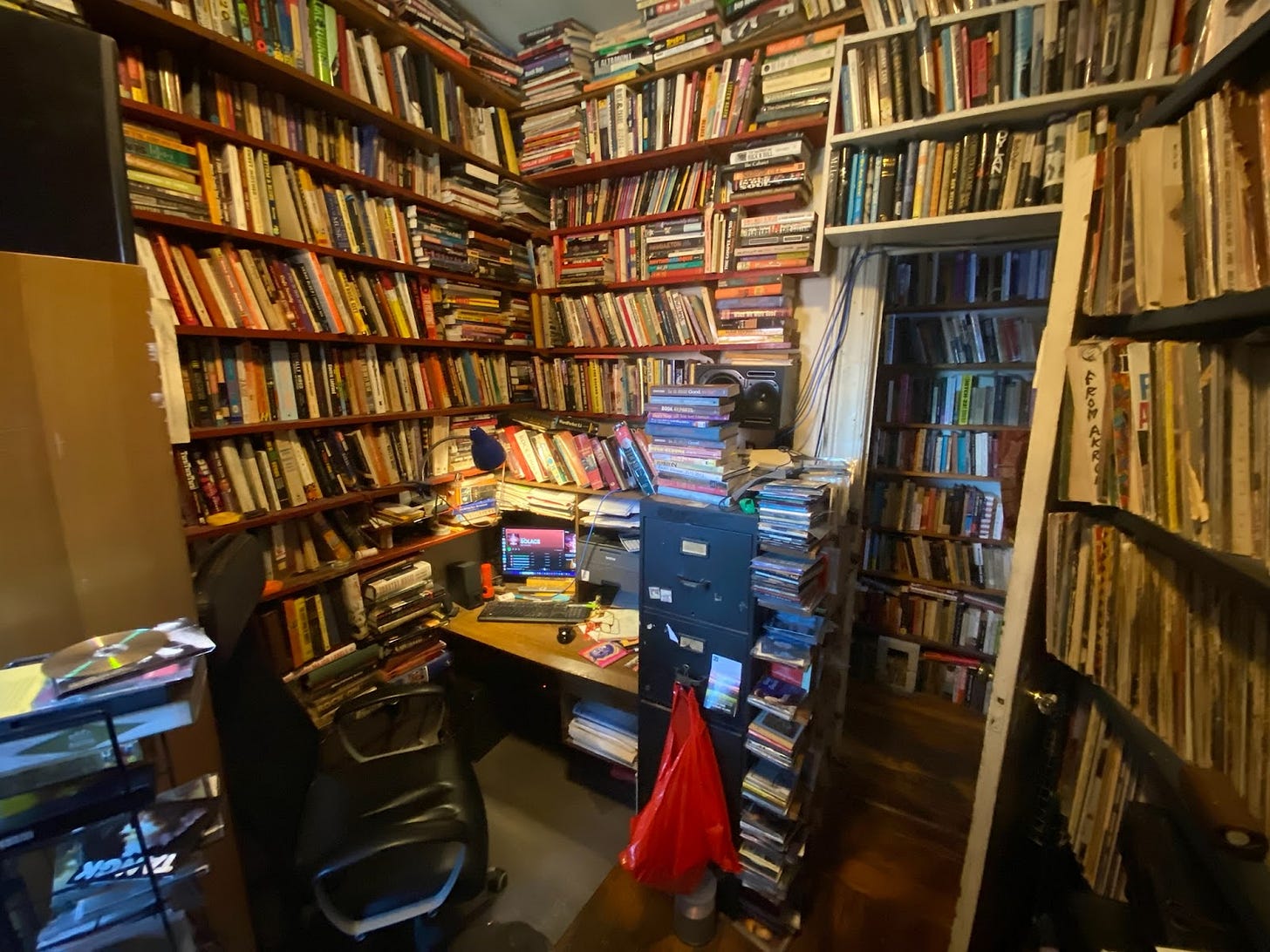

I lived just east of Avenue B in Manhattan from age 23 in 1965, where my $45 walkup comprised three rooms plus a tiny toilet with a bathtub in the kitchen, till age 33 in 1975, by which time I’d taken over a $77 four‑room with a separate bathroom and a modest office where I wrote most of my Newsday columns and then a bunch of Village Voice rockcrit too. Gradually, of course, the thrill of getting LPs free dimmed as more arrived in the mail every day. And pretty soon we’d moved to a seven‑room Second Avenue apartment my wife Carola had found. By then I’d screwed together some industrial shelves—eventually six six‑shelf steel 12‑by‑36 jobs that hold some 240 vinyl LPs per shelf, 1440 per unit, and later there were more. Which means, although some now admittedly hold hi‑fi equipment and others have been retrofitted for compact discs, that most of what industrial shelves etc. remain otherwise unoccupied now accommodate some 36,000 vinyl LPs in our apartment alone—assuming I didn’t mess up the math.

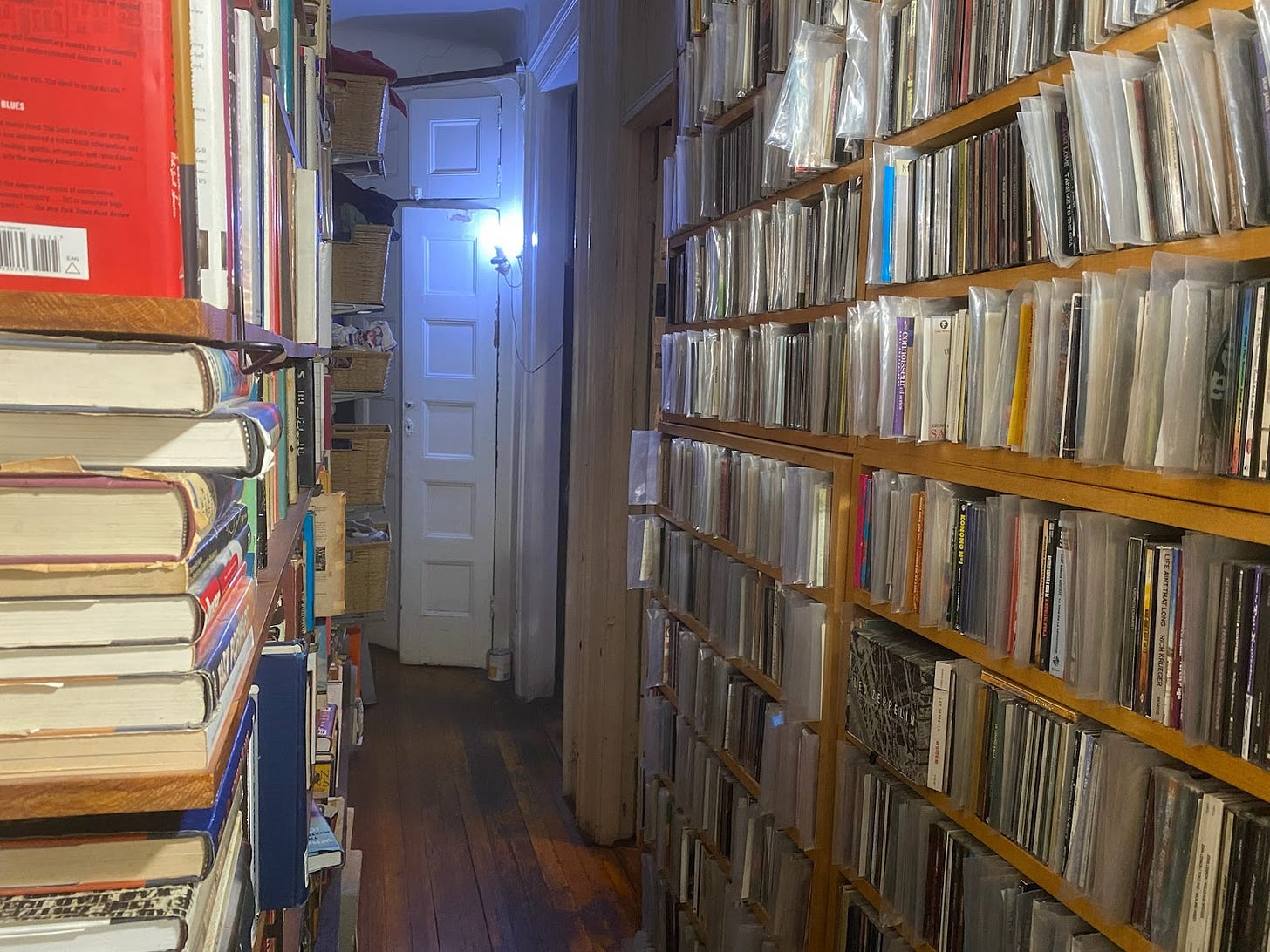

None of the seven rooms in the domicile we’ve occupied for half a century is anything like huge, but wrapped around most of them is a long hallway that takes a right at the bathroom and leads all the way from the front door to the corner living‑room‑plus‑alcove where Carola works. The hallway is functionally an adjunct of a record library that includes not only a big chunk of my accumulated sound recordings but an additional 65 feet of CDs. So I feel kind of proud that—except for a special‑ordered one‑of‑a‑kind seven‑by‑three‑and‑a‑half feat of carpentry, which supports 13 40‑inch CD shelves that in turn accommodate all my A‑list CDs alphabetized from Abba down to, well, Del‑Lords—the hallway also accommodates, you know, books. Plus, well, having converted to CD circa 1991, I now also oversee 65 CD‑ready shelves from 17 to 40 inches long tucked here, there, and everywhere. All are crammed with mostly jewelboxed compact discs that to save a little space I transfer into skinny flexible polyvinyl sleeves if they’ve proven marginal. And since Carola and I are writers who read a lot, there are also all the aforementioned, you know, books, which stretch through every room in the house for a total of something like 400 linear feet. And last as I calculate use value come a mere three file cabinets, 13 drawers spread over three units full of what I’ll just call memorabilia—typescripts, drafts, bios, and press releases, some of them regarding artists lost to history, though as the archivally inclined tend to see it that only increases their historical import. And finally I’m obliged to leave my apartment behind as I unlock the five‑by‑10‑by‑10 storage unit over near Avenue D for which I’ve shelled out ever‑increasing monthly rents for 30‑40 years now. It’s overrun with more vinyl LPs plus old reader mail and old press releases and old love letters and, absolutely, more books.

Does all this add up to an archive? An archive of sorts is the best way to hedge that bet. So to compare and contrast a little I thought it was time to check out the crammed Manhattan living quarters of a few of my aging contemporaries in music journalism and its ancillary career opportunities. In this, what some may consider a grandiose or even dated stanza of my favorite Yeats poem, “Vacillation,” has been pulling the lapel of my T‑shirt for 65 years: “No longer in Lethean foliage caught/Begin the preparation for your death/And from the fortieth winter by that thought/Test every work of intellect or faith/And everything that your own hands have wrought/And call those works extravagance of breath/That are not suited for such men as come/Proud, open‑eyed and laughing to the tomb.” Dismiss this as one more long‑winded metaphor if you like. But be aware that such metaphors do resonate more loudly as you pass not just 40 but 70 and then 80, especially as your health becomes more complex, call it, such as when you’re 73 and your lifemate is diagnosed with cancer, as mine was. So a week later, when we’d accumulated enough moxie to share our thoughts, we learned that in the wake of this revelation each of us had come to hope that he or she would predecease her or him. Each of us was secretly thinking, “I wanna go first.”

So if I do, what then? Well, one thing I know is this: a shitload of work for not just the literary executors named in my fast‑aging last will and testament, two highly intelligent, efficient, and music‑savvy “young” friends who by now are around 60, but also my wife of 50 years come December 21, perhaps with our only child, who is now pushing 40 somehow, ensnared as well. What the hell are they going to do with all this stuff? Will anybody even want it? Because as I assume many of you are still too young to fret about, the answer could well be nope, which as someone whose webmaster calculates that he’s reviewed some 17,000 albums, most of them still situated somewhere in my home or that storage unit, I find dismaying. Admittedly, the onslaught of streaming, in my case mostly via the awkward Spotify, complicates these issues further. Due to what I’ve taken to calling externality because that’s the only decent word I’ve come up with, I find that music on compact disc and less conveniently the resurgent vinyl LP packs a physical authority, or maybe I mean a metaphysical illusion of physical authority, that doesn’t make itself felt so readily when I stream. Although I could be kidding myself, to me it seems as if what I call physicals help me access a frame of mind that informs and to some small but significant extent intensifies my aesthetic acuity and critical commitment, and especially given the old record‑changer trick, where one flat, round, audible object is automatically followed by another that unexpectedly impacts more vividly than its predecessor, usually because I’d forgotten it was up next and found its lead track arresting or the contrast illuminating.

Not that these aural nitpicks have much to say about archives per se, so let me honor distinctions that have been rising regularly from the shadows here: collection vs. library vs. archive. What I’ve been describing—except maybe for the contents of those file cabinets—boils down to the family library. Lest there be any confusion, I mean especially our library of, you remember, books, which—in addition to nine long shelves of nonfiction in the hall and 10 somewhat shorter shelves of fiction in the alcove, a rough count suggests 1000‑plus music bios, histories, and studies in my office per se. But then let’s also specify that the sound recordings (which include many cassettes under the coats out in the hall that for simplicity’s sake I won’t mention again) also constitute a kind of library, a record library for those who don’t necessarily even read music but believe it should be heard first and described afterward. Most of the CDs are by individual artists and groups, but some thousand of them, all catalogued alphabetically in my computer and some 400 shelved alphabetically by title near my office window, are what I designate cdcomps—multi‑artist compilations on compilations from Adventures in Afropea 3 to ZZK Sound Vol. 3.

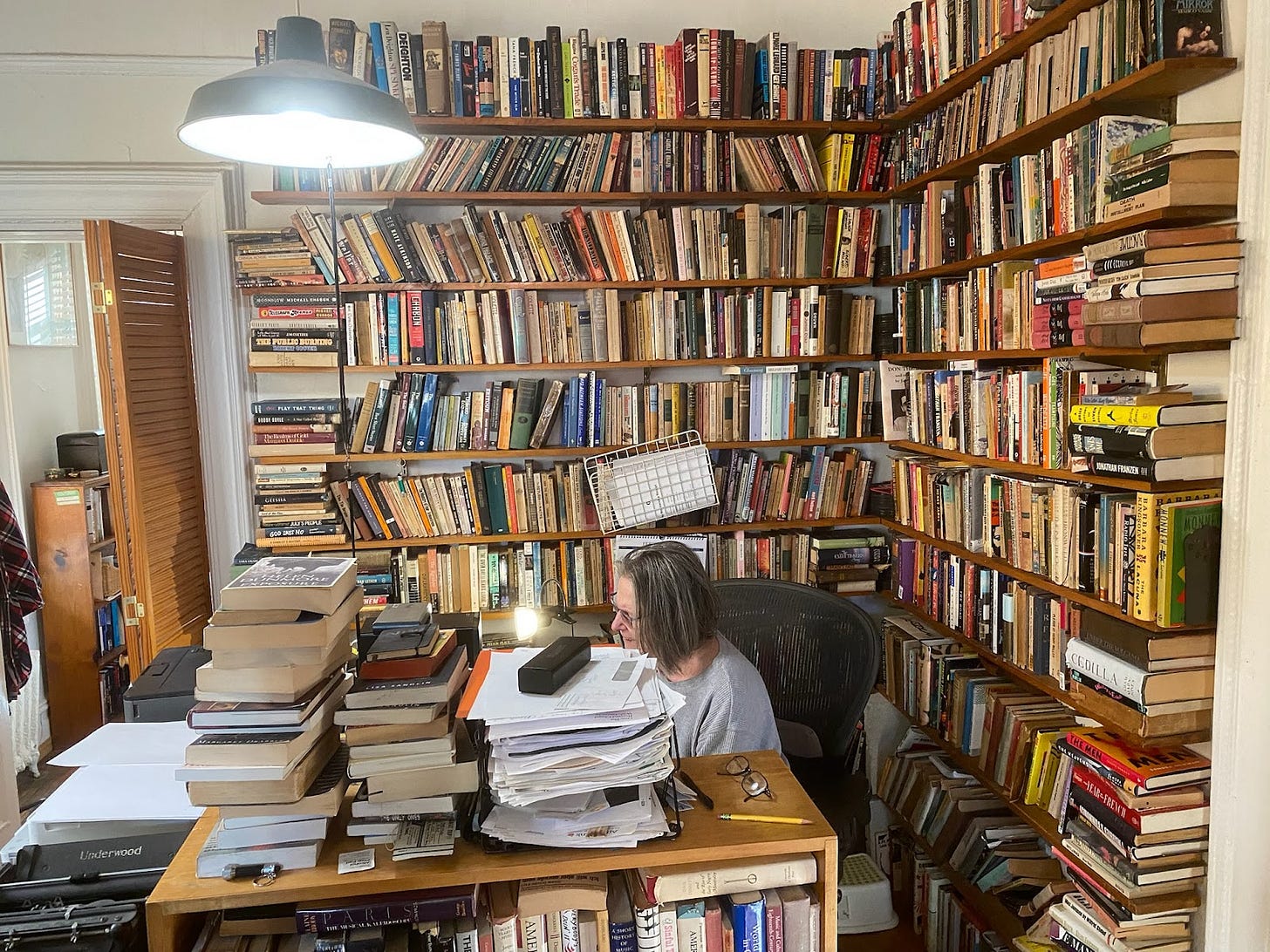

So to return to the concept at hand, you tell me even if you have to guess: does my 12‑by‑six‑and‑a‑half‑foot office house a library, a collection, or mayhap an archive, like for instance of those multi‑artist CDs, most of which have a geographical or stylistic hook. For all I know, I may have accidentally amassed one of the largest stores of such items on earth even though many more almost certainly never reached my mailbox. So for comparison’s sake, at the very least I thought I could do some friendly poking around among not rock critics per se but four somewhat less obsessive old friends and contemporaries, none of them quite as encyclopedic as moi: Robert Christgau, the guy who has no idea where exactly he wants those albums to end up.

Oddly—and I truly don’t know what if anything this “means”—all four of my chosen interviewees are white gay men: Warhol factory hand, Elektra publicist, Ramones manager, and unflappable hustler Danny Fields, gay liberation pioneer plus Hurrah and then Danceteria overseer Jim Fouratt, inventor of rock criticism Richard Goldstein, and my old friend and neighbor Vince Aletti, who reviewed the Jackson 5 at Madison Square Garden to lead the very first week of Village Voice Riffs I edited in 1974. Vince has lived three floors upstairs from me for almost 50 years and thus was available to lend me the 20‑plus ‘70s albums that made my complete James Brown rundown in the first Consumer Guide book possible. But I wasn’t prepared for what I found two weeks ago when I went upstairs to talk legacies with him. Better known now as a Voice and then New Yorker photography critic than as the pioneering r&b and then disco advocate who wrote for Creem and Rolling Stone as well as the Voice, Vince was the Voice’s art editor from 1994 to 2005. So those James Brown LPs I mentioned? He's sold most of his vinyl now, retaining just a few hundred favorite titles. But to my surprise his apartment was jammed with other media, chock full of and dominated by old magazines that are bundled and stacked in waist‑ or chest‑ or shoulder‑high piles over much of his apartment. He plans to sell some of them because at 79, with his writing income diminished, he could use the money.

Attended by three noticeably knowledgeable young men, including a onetime archivist at NYU’s Bobst Library who's now pursuing an art history Ph.D at Stanford, Danny Fields had given such matters more thought. Not unexpectedly because he’s always been a smart guy who gets around, Danny takes a hard line on archives in general. Be it impecunious New York poets transmogrifying Fire Island, which Wikipedia reports had an official permanent population of 292 in 2010, into a gay beach getaway, or Yale offering substantial sums for some of Danny’s correspondence and memorabilia even if the cash has been slow in reaching its appointed destination, he didn’t shilly‑shally about the basic goal, which is to delve into the correspondence and private papers of poets, artists, and other public figures to find out more about them. And to top off my visit I was led to a narrow room where all of us could listen to some music—not the Ramones, whom Fields praised fondly with special affection for Johnny, but also, da‑dum, the Grateful Dead. As the rare Ramones fan who’s always liked the Dead, in some respects the anti‑CBGB band who as Fields quickly noted could play their instruments like few of their rock contemporaries and quickly establish how deft they are technically, sonically, and let’s just call it aesthetically, I was tickled—and also struck by Danny’s choice of artist.

My other two visits proved so enjoyable socially that I had to circle back to fill in the details archive‑wise and learned plenty. I’ve known Richard Goldstein since 1966, when his Pop Eye column brought a strain of rock criticism that proved prophetic to The Village Voice, where he put in decades as both writer and editor until the Hounds of Phoenix bought the Voice and then offed him in 2005, with yours truly soon to follow. I’d chatted with him at several book readings without ever visiting his Christopher Street apartment or meeting his teacher husband Tony. When the talk turned to archives, I photographed their 500‑capacity standing CD shelf and was reminded that they have a country place near Bennington where a smattering of their old books can take their rest. But Richard’s divestiture has been far more thorough than that—32 cartons of papers including most of his Voice bylines and book manuscripts, which latter, with all that prose long since digitized, seem to have little documentary or monetary value. “What they’re looking for,” said Goldstein of the academics who make it their business to round up other people’s papers, “is process,” meaning evidence of dynamic change likely to inflect or possibly even transform how their published works are understood. Nobody seems much interested in typescripts of anybody else’s collected works.

Onward to the great Jim Fouratt, the unflinchingly left‑identified gay activist and music pro whose skills, contacts, charm, and hustle quickly elevated him from Clive Davis’s young special assistant to the kingpin of two game‑changing rock clubs, Hurrah up on West 62nd Street and Danceteria, which moved around south of midtown. Onstage both featured altish rock bands almost exclusively, but in what by then was pretty clearly the decline of disco both also featured danceable ‘tween‑set music, often disco‑adjacent with postpunk or new wave connections—Depeche Mode, Pylon, Medium Medium, the B‑52’s, or as things loosened up maybe even Taana Gardner’s “Heartbeat” or the Funky Four Plus One’s “That’s the Joint.” Neither Goldstein nor I come from much money—his father worked for the post office, mine for the fire department and then the Board of Ed. But Fouratt, who now lives on his social security, was flat‑out poor—a Rhode Islander who got into Harvard but couldn’t afford the tuition. He too has sold some of his papers, mostly for inclusion in Yale’s LGBT collection, and from his club years he’s also amassed some 700 demo tapes by bands hoping to land a gig—quintessential archive stuff guaranteed to be long on process.

Before I’d even begun the research I’ve been condensing here, various advisors had convinced me to face the music and dig into that storage unit, which over the past decade I’d glimpsed seldom and rummaged through barely at all. And once inside I encountered many surprises worth pondering, including a sealed La Monte Young set said to be worth nearly two grand and several batches of the aforementioned love letters. Most of the more recent records I no longer recalled by name, including a substantial smattering of the DIY 12‑inches that started showing up in the mail circa 1990. These I held onto not because they rang my chimes but because it would have been venal to just discard the kind of one‑offs in‑it‑for‑love fans’ hearts tell them to put their own measly bucks into. I wouldn’t be altogether surprised if a few of these turned put to be legendary rarities worth holding onto or putting up for sale. But I also think that at this point it would be silly to spend valuable time trying to find out.

After all, whether as a convention more honored in the breach or an ironclad rule of thumb, the Fire Island correspondence Danny Fields passed to Yale is so archival it’s archetypal; the papers he’s curated, let’s call it, illuminate that un‑weatherproofed strip of sand as both real estate and mother earth, exemplifying the kind of process Goldstein believes archivists crave. But at the same time it made me wonder—to what extent do such scholar‑archivists enrich their and our understanding of the New York poets who were helping transform Fire Island into real estate. Which made me wonder about the extent to which such archives as my heirs might have at their disposal will be taken up by scholars unknown to me in the belief that they suggest truths and tendencies not acknowledged much less confronted in the millions of my words now preserved on my website and in my eight published books. Long ago in this process the great jazz critic Gary Giddins hooked me up with a New York Public Library archivist who’d overseen a Giddins collection. I have so much love for the NYPL, without which I might never have become a writer, I’ve made it my number‑one charity ever since I started itemizing my taxes in my twenties. But when the archivist told me he didn’t need my books because he did, after all, work for this sizable library, I was sad. It’s my published writing, not my correspondence or for that matter my college papers, that I hope a few readers remember and even enjoy after I’m gone.

Considering all this, I found myself struck by one of the images this particular PopCon has chosen to make its own: the one where a young man is sitting in front of a big thick wall of LPs—as opposed to, note, CDs on the one hand or master tapes on the other—and I assume pondering which album to play. This tickled me, and just a day or two after encountering it I found myself visiting my old colleagues Nick Sansano and Dan Charnas at the new Brooklyn offices of NYU’s Clive Davis Institute of Recorded Music. I stopped teaching at Clive after a decade or so in 2017—I was working too hard, and my annual physical proved it. So I’d given little thought to what I’d find in Brooklyn, which as it turned out was a palace: 12 full floors equipped with numerous high‑end recording facilities including a replica of the Beastie Boys’ Oscilloscope Studio, thus accommodating a much larger student body compared to the pioneers who learned their craft mostly at the Institute’s old 194 Mercer Street digs, where the classrooms were sparse enough that I usually taught elsewhere on campus.

So after taking the tour I sat down with Nick Sansano and revealed to him my fantasy of my LP collection with CDs too for sure being put to use in an actual room with chairs in it where bare‑eared or perhaps headphone‑equipped young music nuts like the expanding student body at Clive. And to my considerable surprise Nick loved the idea. So is something like that gonna be what becomes of at least part of my own archive? As the Orioles put it in 1948 even if you’ve never heard of them, which chances are you haven’t, it’s too soon to know.