Guest Post: Tim Quirk

Some thoughts on writing about music from someone who has both made art and written criticism of other people’s art.

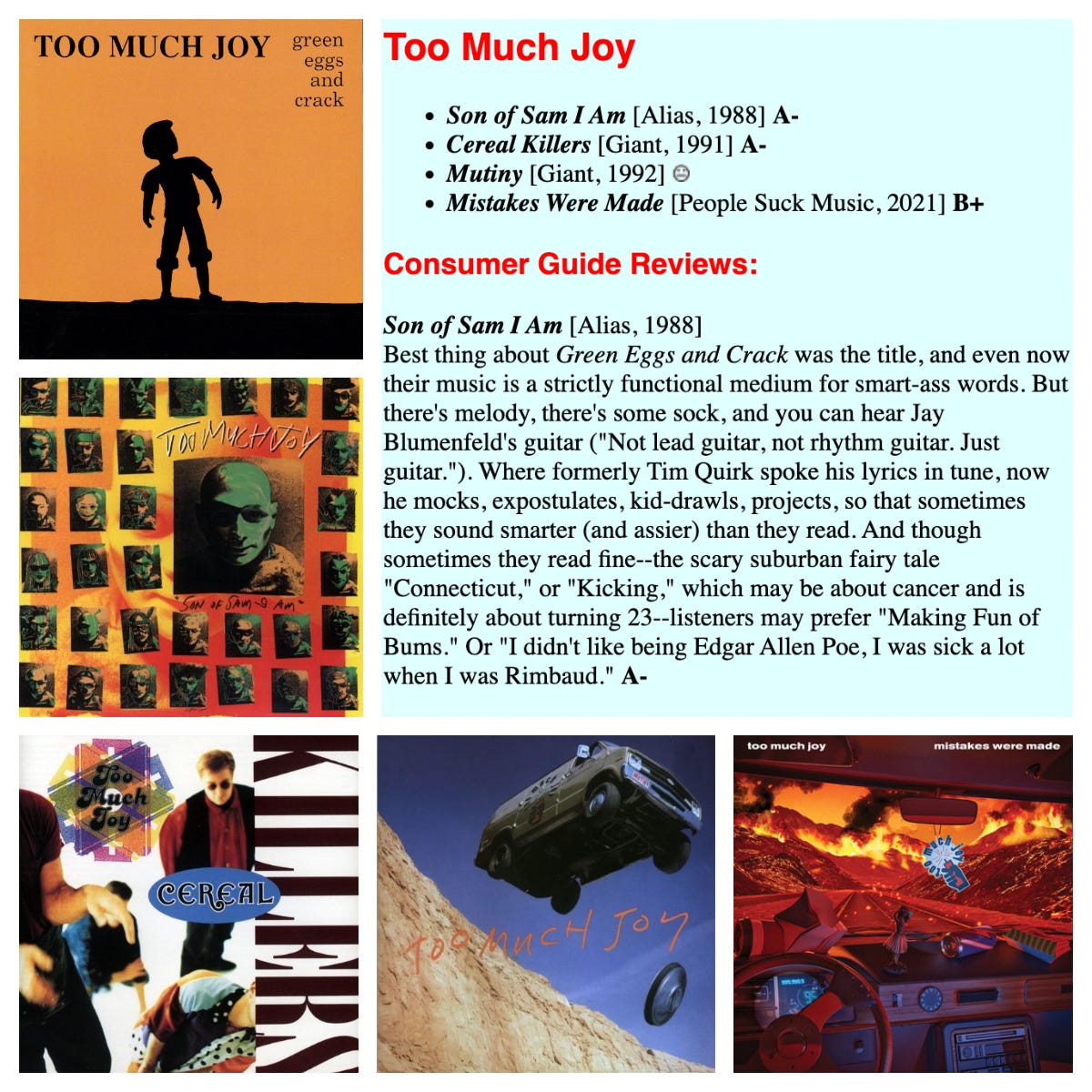

In April Robert Christgau celebrates his 80th birthday, and so guest posts on And It Don’t Stop will mark the occasion and give him some time off. (Not too much time off: there’s still a Consumer Guide next week.) The first is from Tim Quirk of Too Much Joy.

When a picture of Charli XCX in a t-shirt reading, “They don’t build statues of critics” briefly took over my Twitter feed last month, I flashed back to multiple awkward encounters I’ve had with artists when working as a music writer: a Butthole Surfer suggesting he’d eventually be wiping his ass with Raygun magazine, the publication that had sent me to Texas to talk to his band; or Tre from Green Day accusing me of getting “paid money to pick the punk rock scene apart,” then asking, “Why are you writing in the first place?”

I gave Tre the same answer I’ve given every musician who’s ever suggested to me that music writing is a suspect endeavor: “That’s like me saying why are you singing.” I asked him what he and his bandmates talked about all day, and he admitted, “We talk about music.”

“Right,'“ I said. “So, people writing articles about music are just having that same conversation with people they haven’t met.”

At a fundamental level, all culture is in conversation with itself. As someone who has made art and written criticism of other people’s art, I’m convinced that both exercises are mostly just attempts at A) trying to be understood and B) hoping to connect with other human beings who see things the same way.

So why should purveyors of one form of attempted human connection expend so much energy hating on purveyors of a different form of the same thing?

Well, duh, I’ve answered my own question already: because B is often in conflict with A. If you’ve spent months or years crafting a work of art that reveals your true self in a way no other form of expression can, you’re going to get righteously indignant if somebody suggests that self is lacking, or ugly.

But here’s a thing I learned reading criticism of my own work: reviews, whether positive or negative, are meaningless when you disagree with them. They only hurt if the critic has actually accomplished goal A, and understood who you are and what you’re trying to do. If that happens, but B doesn’t (ie, they understand you, but they disagree that your latest work of art is awesome), then it stings.

Sure, it’s mildly annoying if you’ve worked hard to create the perfect chocolate ice cream cone, and some reviewer writes the equivalent of, “Chocolate is awful. Strawberry is the best.” But it’s nothing you really need to think about ever again. What hurts, and sticks with you, is when you’ve labored long and hard trying to craft the perfect chocolate ice cream cone, and some frighteningly perceptive critic says, “This looks like chocolate but it tastes like strawberry.”

There’s a reason I’m writing all this on Robert Christgau’s Substack1. He knows his chocolate from his strawberry. More importantly, he knows MY chocolate from MY strawberry. Back in high school, Christgau was one of maybe three critics whose positive review could get me to plunk down money on records I hadn’t yet heard. I had two friends at the time who liked the same music I did, and we’d spend lunch hours in the library, flipping through copies of The Village Voice, nodding enthusiastically as Bob dissected what made our favorite bands so great, or dismissed the ones we considered pretenders, in 200 words or less.

It wasn’t just that he seemed to share my tastes; his reviews regularly told me more about myself than whatever record he was analyzing. He had a novelist’s ability to articulate thoughts I hadn’t realized I had, whether he was raising concerns about the best song on Boys Don’t Cry (“The last thing we need is collegiate existentialism nostalgia”); helping me understand why I was unmoved by Oingo Boingo (“these guys combine the worst of Sparks with the worst of the Circle Jerks”), or getting downright prescient about U2’s future sins when reviewing Boy (“their echoey vocals already teeter on the edge (in-joke) of grandiosity, so how are they going to sound by the time they reach the Garden?”). He also explained why I liked records I wasn’t sure I should—calling X’s debut LP “a smart argument for a desperately stupid scene,” for example, or noting that my two favorite Bow Wow Wow songs, “Sexy Eiffel Towers” and “Louis Quatorze,” “almost justify Malcolm McLaren’s dubious project of inventing a sex life for his fourteen-year-old Galatea.”

Once you feel so aligned with a given critic, reading their reviews of your own work can be a fraught experience, because you can’t dismiss anything negative they might say as a mere matter of differing tastes. But as an adult who formed a band with those same high school friends, I’ve found I’m still nodding when he reviews our records (though maybe a bit less vigorously when he’s bemoaning mistakes I secretly know we’ve made). I’ve never felt as though he’s judging our work—it’s more like he simply perceives it.

And those perceptions have unit-shifting power! We were on tour the month he reviewed Too Much Joy’s sophomore album, Son of Sam I Am. I’ll never forget the promoter in Ames, Iowa informing us at soundcheck that the show had sold out. We tried not to act like that was a surprising thing that had never happened, but we were quite surprised, because it had never happened, and Ames, Iowa was a very weird place for it to finally occur. Then the promoter showed us the A- Christgau had given us in that week’s Voice. Back before the Internet, reviews like that could fill a club.

The grade made me vaguely proud, but I was more taken by the way his blurb made me feel seen, even when he was being less than complimentary. “Best thing about Green Eggs and Crack was the title,” he wrote of our debut2—a sentiment I should note was even then shared by every single member of the band.

My favorite part of that blurb was neither a compliment nor a criticism, just his simple observation that a song called “Kicking,” “may be about cancer and is definitely about turning 23.” That line seemed particularly smart because a writer for the San Francisco Chronicle had recently called me up to ask me if I was OK after hearing the tune, leading to an awkward conversation in which I had to explain that, though the narrator of the song claims to have cancer, it was just like, you know, a metaphor.

Four decades later, I’m still nodding at Bob’s reviews (just recently I marveled at the way he distilled my reasons for merely respecting rather than actually loving Radiohead into five simple words: “such a wan emotional palette”). And he still moves units: last year, his blurb for TMJ’s first record in 25 years came out a month or more after release date, by which point daily sales had settled to a pretty steady little line on our Bandcamp graph. So I’m confident the healthy spike we saw the day he gave that album a positive grade was solely due to the fact that he liked the record, and told his readers why.

If I didn’t really need him to tell me in that same review that my heroes Randy Newman and the Clash are geniuses, whereas my bandmates and I are merely smart, I also can’t really argue with the sentiment, especially if I still want to believe something he wrote back in 1991, in what I consider the highest praise my band’s ever received, when he approvingly cited two cheap laughs from our third album before noting that they were, “longer on self-knowledge than most dumb people I meet.”

I consider self-awareness one of the highest virtues. I listen to music and make my own and read criticism and write my own because all of those activities are different ways of trying to achieve some.

But it’s comforting when the picture you have of yourself is shared by others, whether or not they think that picture’s pretty. If I haven’t made it clear already, I want to be understood much more than I want to be praised. Both are great, when you can manage it. But if I can only have one, I’ll always choose understanding.

And Bob understands.

Several reasons, actually. The first is that he turning 80 this month, and some of his pals are giving him the month off as a present. The second is that Joe Levy, who edits this Substack, asked me if I’d participate, and suggested maybe I could write about what it’s like to be reviewed by Bob. So if you think writing a piece about that is even more egotistical than releasing or reviewing music in the first place, please take it up with Joe.

Given how hard that record was to find (we’d self-released the thing, and most of the 1000 copies we’d pressed had been mailed to college radio stations), I was as impressed by his ability to get his hands on a copy as I was by his patience in sitting through even one listen. Few critics would have bothered to attempt either.