Graffiti Artist

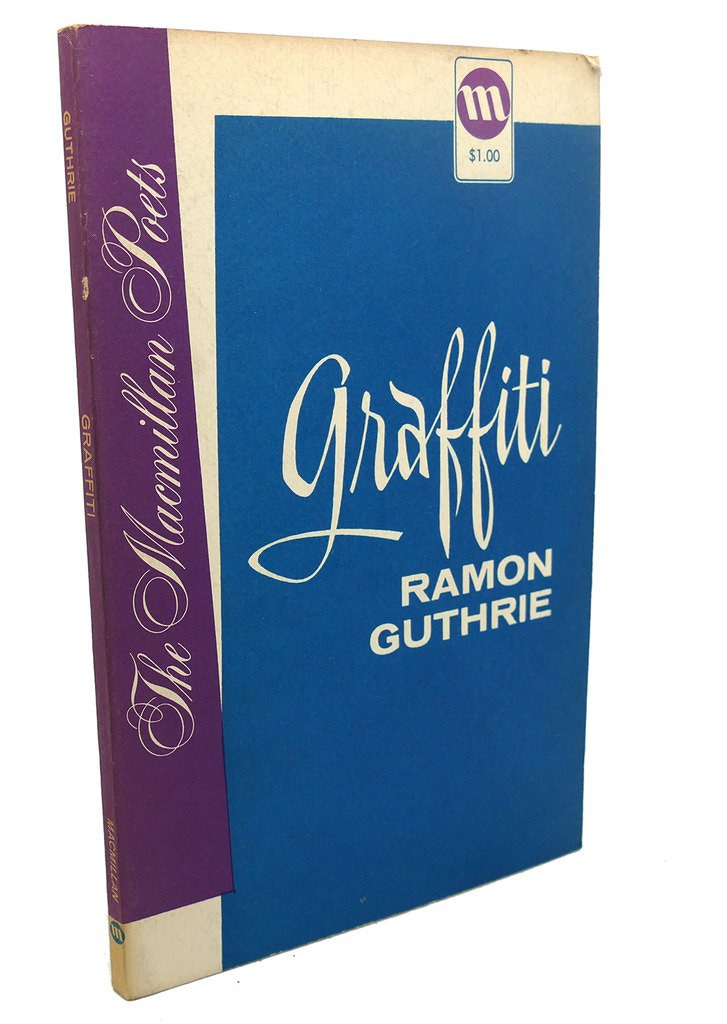

Ramon Guthrie, "Graffiti" (1959, 72 pages)

A month or so ago, answering an Xgau Sez question regarding my few thoughts on what is called classical music, I was reminded of the one such work except perhaps Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring and maybe a Beethoven symphony (Fifth? Third? Seventh?) that I’ve listened to front to back: what in 1959 I was taught to call Beethoven’s C Sharp Minor Quartet though its official cognomen is String Quartet No. 14. The teacher who preferred the more descriptive usage was in the French department: the then 62-year-old Ramon Guthrie, who in the age of Wikipedia I can sum up as an NYC-born poet, novelist, and professor who was raised by his single mother in and around New Haven, enlisted to fight in World War I, remained in Europe when the war was over, and by the time I met him had become a fixture at Dartmouth College who among other things taught a seminar devoted entirely to Marcel Proust’s million-and-a-half-word A la recherche du temps perdu if you were a French major or Remembrance of Things Past if you were a book-mad 17-year-old set on getting this monster under his belt. The main thing Guthrie demanded of his class was to prove they’d done the reading by answering a simple, factual 10-question quiz based on that week’s assignment and then absorbing and discussing his commentary. When I taught at NYU decades later, I adopted this just-make-sure-they’ve-read-it approach myself.

The only “quality” school to accept me into its class of ‘62 (where, as in high school, I was the youngest student due to my late-April birthdate) Dartmouth was a fratboy citadel that helped inspire Animal House, a less intellectually stimulating place than I’d dreamed. But there were plenty of exceptions, and—like my advisor John Hurd, who at a crucial juncture told my parents that he too had tried his hand at journalism before making his decision for academia—Ramon Guthrie was one of them: a congenial and kindly old guy who once spearheaded a move in the department to raise every grade handed out by the captious snob who taught French drama, netting my laborious late-existentialist disquisition on Samuel Beckett’s Endgame the full A it deserved instead of the B the creep tried to stick it with. Made me feel better about myself, that A. The details of Guthrie’s colorful biography was unknown to any undergraduate in my smallish circle. But somewhere in there I laid down a buck on his 72-page poetry collection Graffiti, which if I pique your interest is available for 16 dollars at Amazon and 18 at Thriftbooks.

Although I loved Allen Ginsberg’s Howl, was bowled over by E.E. Cummings at 17, and hitchhiked America with my complete Yeats in my backpack, I’ve never had much time for poetry beyond my belatedly discovered William Carlos Williams since I followed in John Hurd’s footsteps only I stuck with journalism. But whenever Ramon Guthrie crossed my mind I found myself recalling a single line of his poetry: “You an’ me, bister, been giraffes.” Reading Graffiti in its entirety, which is not a big job, I found that line, which after a brief Baudelaire intro begins the 20-line “To and on Other Intellectual Poets on Reading That the U.S.A.F. Had Sent a Team of Scientists to Africa to Learn Why Giraffes Do Not Black Out”—by my lights an admirably eccentric little poem, although never it never quite lives up to the word “bister,” which Guthrie may have made up, although Merriam-Webster reports that it can mean “a yellowish-brown to dark brown pigment used in art.”

Reading Graffiti front to back, often murmuring lines aloud as I lay in bed, was an easy-peasy pleasure—marking it up in pencil as I’m prone to do, I declined to touch only eight of its 33 selections, nine of which detail the exploits of a disruptive figure called “The Clown.” That Guthrie had his own notion of the intellectual landscape he dared trespass is summed up nicely, not to say brazenly, in the first three lines of one called “Postscript in Another Hand,” which admittedly won’t seem so venturesome a century after the fact: “Could it be both were wrong,/Old Ez post-temporarily folding his blankets,/Mr. Eliot posteriorly acquiring pew-sheen?” Clearly he had his own disrespectful view of what was still the poetic pecking order back then, and as a Cummings-to-Yeats fan myself I say no wonder I liked this guy—no Pound or Eliot for him.

I can’t speak to Graffiti’s library availability except to report that his work seems to be down to one title at the New York Public Library, my top donation destination not counting ActBlue, which I hope you reach out to, as they say, while you can. So having lured you this far, I’ll take the liberty of quoting my favorite Graffiti poem in full. Its title is “Gemini.”

Twins in French are jumeaux

Jument put into English is mare

To drink is boire

but they are not the same:

that is as close as they can ever get:

always one is cooler, sharper,

grosser, downier, more immediate

or less substantial than the other.

There is woman and there is femme

And they are not the same

even when you apply

both words to the same person—

though, all in all, un homme

is not too unlike a man (functionally, at least)

And there is amour and love

What either of them is I cannot say

except that they are not

identical

One of them is much more

something or other than the other.

They are as different as

to die and mourir

Though how to define

their differences either only

Dieu knows or God sait.

So, read that one? Pretty good, right? Only it turns out there’s more, to be precise a 1971 New York Times review of a second Guthrie collection called Maximum Security Ward by one Julian Moynihan, whose name I maybe should recognize but come on—this was 54 years ago. Instead I will simply quote two lengthy sentences. Ahem.

“Why is it that during the last 25 years we have heard so much of say, Robert Lowell and, latterly, of Allen Ginsberg and nothing at all of Guthrie, who is slightly better than both at their best?”

And then: “Halfway through Guthrie’s Maximum Security Prison I repaired to my local university library and found Guthrie’s Graffiti (1959), a volume of verse as interesting as Yeats’s Responsibilities.”

Turns out there was a Maximum Security Prison at Thriftbooks. I just bought it.

I no longer remember what prompted me years ago to go to Bookfinder.com for Ramon Guthrie’s books—maybe something in one of Carey Nelson’s books— but I found several at reasonable prices. Including a copy of Asbestos Furnace that turned out to be signed. Been a while since I read them but I remember liking them I’ll get them off the shelves again

Essential.