A Lifelong Southern Rock Opera

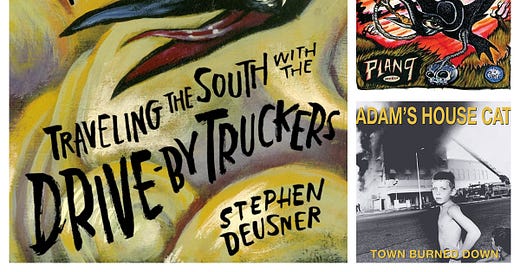

Stephen Deusner, "Where the Devil Don't Stay: Traveling the South with the Drive-By Truckers" (2021, 320 pp.)

The Drive-By Truckers are a great band that kind of got lost in the shuffle. Spawned circa 1996 by son of Muscle Shoals Patterson Hood and his college roommate Mike Cooley, with a young version of the unstoppable Jason Isbell beefing them up for a spell early on, they’ve since generated 14 regular-release studio albums plus enough all-the-way-lives, best-ofs, and one-offs to bring them well over 20, and just about all of the core 14 are chocked with songs that set sharp, ambitious, down-to-earth lyrics to tunes that stay with you whether they’re literally catchy or not. Neither partner Hood nor Cooley is a spellbinder on his custom-made guitar or gifted with the kind of voice that captivates you on timbre and technique alone. Though they admire Southern bands from alt-pop R.E.M. to stars-and-bars Lynyrd Skynyrd, neither approach is for them. Nor in the end is it all about the songwriting at which they excel. It’s bigger than that. In Where the Devil Don’t Stay: Traveling the South With the Drive-By Truckers, Stephen Deusner makes it his business to give them the credit they deserve.

There are many first-rate biographies of individual rock and roll heroes: Rick Bragg adding muscle and detail to Nick Tosches’s kick-ass Jerry Lee masterstroke, RJ Smith earning his claim to the scandalously underdeveloped Chuck Berry franchise, Howard Sounes’s probing Dylan bio, Nelson George and Alan Leeds’s keen selection of James Brown essays, David Ritz topping his fleet of solid as-told-tos with Etta James’s superb Rage to Survive, and there are more. Group bios, however, are harder to come by—I’d limit the major highlights I’ve encountered to Hunter Davies and later Philip Norman on the Beatles, Jon Savage on the Sex Pistols, Robert Greenfield’s rich account of the making of Exile on Main Street, Carrie Brownstein explaining Sleater-Kinney as she escapes her birth family.

All such highlights granted, however, Deusner’s book is different and deeper. Not only is his research phenomenally thorough—he interviews almost every major player at length and taps many less crucial figures—but he makes himself part of the master theme that renders this rock bio so sociological. That’s because, like most of the principals in the band or out, he is a liberal white Southerner who’s come to terms with the many contradictions that arise from that life choice. His father a lawyer in a western Tennessee town ruled by Sheriff Buford Pusser of Walking Tall renown, he spent summers at his maternal grandmother’s place 200 miles south in Birmingham, then and now overseen by a 56-foot statue of the Roman god of fire Vulcan and situated a few hours east of Muscle Shoals, a crucial soul hub back when Patterson Hood’s father David Hood manned the bass in the legendary Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section. Patterson started an alt-rock band called Adam’s House Cat with Cooley in 1985. Soon the pair were frequenting and then settling in the most bohemian burg south of the Mason-Dixon Line, the college town of Athens, Georgia. And there mid-decade the Drive-By Truckers congealed, releasing their debut Gangstabilly in 1996 and follow-up Pizza Deliverance in 1999, with drummer Brad Morgan a permanent fixture by the turn of the century and the more restless Jason Isbell on guitar, soon joined by his bassist wife Shonna Tucker. The crucial turning point was really more a process, in which Hood decided that the big project they’d dubbed Southern Rock Opera needed, well, a George Wallace song, and to be clear not a positive one.

This is the point in Where the Devil Don’t Stay that Deusner’s history as the son of a liberal lawyer meshes with Hood’s as the son of a white soul musician. And it’s also the point when Deusner starts to ruminate on what it’s like to grow up white in a South where all those boyhood Buford Pusser games seem in retrospect as limited as they are prototypical. The book has been detailed and compelling long before it reaches this juncture and for sure Athens is a fine little haven of a municipality whose history and sociology are worth encountering in this kind of detail. But note that in the end Hood emigrated with his family to Portland, Oregon, and that that wasn’t all. The strained marital commitments of every touring musician in the world are here. So are the myriad complications of Lynyrd Skynyrd, who both Deusner and Hood recognize as a band that thrived artistically under Ronnie Van Zant’s complex, contradictory leadership and then perished spiritually when Van Zant was killed in a plane crash that’s as rich a symbol of the perils of the road as any touring musician could want or fear. It’s the story of a proudly Southern band that would not permit the Confederate flag to fly at its concerts no matter how loudly displaced Skynyrd fans felt otherwise. One of its strongest moments, should you care to keep an eye out for it, comes close to the end: one of the bitterest tear-downs of the supposed nobility of slavemaster Robert E. Lee I’ve ever encountered.

Everything Deusner has to tell us about the evolution of this remarkable band is of interest. They’ve led a long, complex, and idiosyncratic artistic life that’s far from over. And their personal lives posit a gratifying alternative to a South still all too beholden to the rhetorical distractions of preachers who bemoan the “Lost Cause” and whose own rhetorical path is to “extol the love of God and then leave the pulpit to do unspeakable things.”