Roll Over Joseph Pulitzer

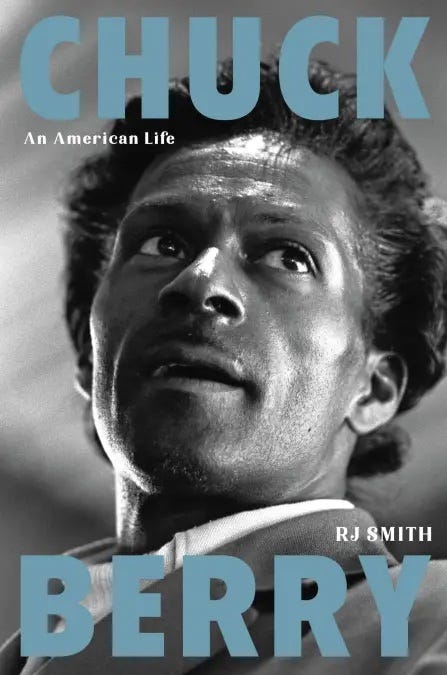

RJ Smith, "Chuck Berry: An American Life" (2022, 415 pp.)

Counting Chuck Berry: The Autobiography, begun during a brief 1979 prison term and finished in the mid ‘80s, RJ Smith’s Chuck Berry: An American Life is the fifth biography I’ve read of the man who invented rock and roll, and so much the best that the sparseness of its reviews makes me mad. “Wish I believed it’ll win the Pulitzer it deserves,” I emailed RJ after downing its 385 pages. But I did believe this thoroughly researched account of a bona fide American genius who died at 90 in 2017 would get the full-bore coverage due not just people’s prodigy Berry but established pro Smith, whose credentials for this topic are triangulated nicely by his biographies of original funkmaster James Brown and Americans photographer-auteur Robert Frank plus The Great Black Way: L.A. in the 1940s and the Lost African-American Renaissance.

I assume that among other things this negligence reflects Berry’s well-documented moral turpitude. No one blames him anymore for the penny-ante JD spree that cost him three years in stir up to the day he turned 21 in 1947, and most regard the low-level tax evasion he did four months for in 1979 as nugatory. The sex stuff, however, is different. First there was the 20 months he served in 1962 and 1963 for violating the Mann Act, a/k/a the White Slave Traffic Act, with a 14-year-old off-and-on prostitute he claimed with some justification he thought was older. And because the evidence was obtained illegally in what Smith establishes was a racist vendetta by white bigwigs from in and around Wentzville, Missouri, 40 miles west of Berry’s native St. Louis and his home town for half a century, he did no time for the sex tapes his enemies there unearthed. Many of these starred himself and numerous women, some of whose feces he ate; many others were videos shot clandestinely in the ladies toilets of a restaurant he owned until their existence was revealed, a few of which featured subteen girls.

Although he died survived by his wife Themetta, who he married in 1948 and in crucial respects seems to have loved all his life, Berry was apparently one of those male celebrities who—like Georges Simenon and Wilt Chamberlain, although less inclined than those obsessives to the once-and-out wham-bam—numbered his female sexual partners in the thousands. Most of those partners were white, as was Francine Gillium, hired as his secretary when she was a 20-year-old college student in Pittsburgh and still in his employ when he died six decades later. Berry’s autobiography begins with the tale of how his great-great-grandmother, the widowed inheritor of a Kentucky plantation remembered solely as Mistress Wolfolk, almost certainly conceived Chuck’s light-skinned great-grandmother Cellie with a Black house servant rather than purchasing and adopting her as an infant in New Orleans as she claimed. To me it seems more than possible that Mistress Wolfolk haunted him all his life—and that her revenant helped compel him to achieve the cross-racial miracles and anomalies so central to his genius, including the musical ones. But compulsive sex makes for a hectic lifestyle, and for sure some of Berry’s bedmates feel he did them dirt, although not any more than, say, Bob Dylan’s somewhat less numerous and more glamorous ones. But there seems little doubt that these relationships were fundamentally consensual, while the bathroom tapes he never went to trial for are of a different order—they definitely weren’t consensual, and in some cases involved minors. So of course Berry’s funeral attracted, as Smith reports, protesters carrying signs like “Your idol is someone else’s abuser.” That is likely one reason Chuck Berry: An American Life isn’t getting the literary attention it deserves.

Then there’s another factor, which RJ’s and my old Village Voice colleague Nelson George has laid out in an admiring Substack review subtitled “Thoughts on a new biography of the rock & roll pioneer.” “Chuck Berry, who did as much to revolutionize music globally as any of black music’s many other giants, usually doesn't get listed alongside the acknowledged African-American greats,” George observes, and declines to attribute this solely to Berry’s many shortcomings as a human being. Instead: “When black folks talk about the most important black musicians of all-time, they tend to elevate jazz artists (Duke Ellington, Miles Davis, John Coltrane) or R&B icons (Aretha Franklin, Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye) to their personal Mount Rushmore. . . . For many generations of black folks rock & roll has been seen as ‘white music’ that isn’t relevant to our contemporary existence.”

I don’t know why George omits a third black music stream at least as vital and contemporary: James Brown’s funk and the hip-hop it engendered. But point taken. With African-Americans finally recognized by white people as the secret of American pop’s worldwide renown, “rock and roll” as a genre comes to seem more and more marginal, especially in its guitar-driven form. Both of the two hottest draws in today’s pop-rock, Taylor Swift and Harry Styles, have migrated decisively from guitar-based to keyboard-based over time, and there wasn't much Chuck in their music to begin with. But insofar as all white rock bands trace back to the Beatles and the Stones and let’s throw in the Beach Boys too, they owe the man. “If you’re going to give rock and roll another name you might as well call it Chuck Berry,” John Lennon famously said, while Keith Richards was the driving force behind the Taylor Hackford documentary Hail! Hail! Rock ‘n’ Roll, which Berry did his perverse best to undermine although he turned out to be just too talented to ruin it altogether. And while it’s true that today’s alt-rock guitar toters, a vanishing breed in any case, seldom mimic his licks, they owe him sonically anyway.

But that’s the least of it, and no other Berry biographer has understood how much more there is. The guitar licks everyone knows about even if the most literal versions of those licks have faded some from the collective soundscape. But early on, when the surprise 1955 chart success of “Maybellene” suddenly rendered the high-and-clear-voiced 28-year-old a successful touring musician, a big step forward for a St. Louis club pro scraping by, Smith homes in on the details like no one before him: how Berry learned to acquire nourishing food in locales where most restaurants wouldn’t sell to him out back much less let him in the door, how he figured out and put to musical use the way his guitar sound shifted both texturally and decibel-wise as he roamed the stage, how his bands created lyrics interactively from the ground up with Chuck providing most of the verbal facility to arrive at an amalgam of words and music which for sheer human reach and impact merits comparison with Mark Twain and if you want to get huffy about it Philip Roth too. And later on Smith not only enlists Black rock guitarist Vernon Reid to expatiate on Berry’s seismic cultural impact, he enlists jazz pianist Vijay Iyer to take that impact to the next theoretical level. “What is the sound of someone asserting their personhood in the context of their personhood being legally denied or revoked?” Iyer asks, then goes on to adduce “an insurgent quality and a resistance—it becomes more than just ‘bodies are present and I hear them moving’: these are defiant human beings.”

This is a rich book, full of tales and details and contradictions and ramifications I’ve barely hinted at. And I admit that it feels a little strange to attach so much Black consciousness to an African-American artist who for reasons both valiant and self-serving created music he designed to appeal to white people. But in the end the very best thing about it is that Smith insists on racializing his narrative. I’ve barely suggested all the twists he folds in, and you have every right to find some of those I’ve isolated alarming. But now that Chuck Berry truly does have no particular place to go, I prefer to believe that RJ Smith has made of his life story a strange thing Berry would have been happy about to whatever extent happiness was within his emotional compass: to stick that story not only in our ear but into the uneasiest byways of our aesthetic values and political subconscious.