Xgau Sez: September, 2020

Several 30 seconds of greatness, formalists formally considered, Ray Davies informally considered, list-making explained, hip-hop unexplained, and the "The Harry Smith B-Sides" expurgated

Hi Bob, thank you for your years of attentive pleasure. I’m closer to my own delight thanks to how you’ve taught me to listen. Curious: what comes to mind when you think of your favorite 30 seconds of music? (A friend I asked this offered Herbie Hancock’s intro to Wayne Shorter’s “Infant Eyes” and Doug Martsch’s bonkers guitar solo in Built to Spill’s “Girl.” I’d choose, I guess, the horns-answered-by-piano-rumble ending the first chorus of Lee Dorsey’s “Get Out of My Life Woman” or the heavenly feather-light guitar that enters at 9:26 in Franco’s “Tailleur.”) Does your enjoyment attach to moments (a brief solo, a crescendo, a vocal flight or cry, a musical phrase of paralyzing beauty) as much as to whole songs or albums? Grateful as always. — Jay B. Thompson, Seattle

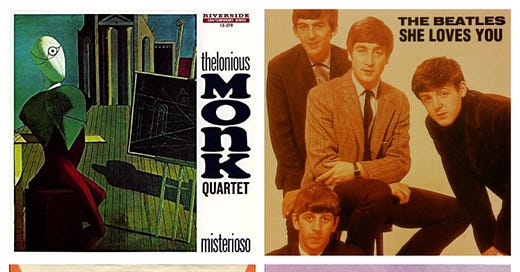

My first response to this impossible question (because there are so many and they’re so fleeting) was that I treasure moments much longer than that, especially whole songs and beyond that whole albums. Only then I immediately began thinking of possibilities and checking them out. So having determined that Johnny Griffin’s solo on Monk’s “In Walked Bud” was far too long I’ll leave my answer at first-response impulses unless Carola has the perfect answer when we discuss this, as we will. So the two artists who first occurred to me were Wussy, where the “Teenage Wasteland” lead proved a nonstarter before the “Airborne” verse with the “yours pile”-“floor tile” rhyme held up to 30-second parsing, and then—how could I forget??—the Beatles, whose first “Yeah yeah yeah”s-plus-verse on “She Loves You” and “Please Mr. Postman” outro are both a touch short but what the hell. Only then I thought of Franco & Rochereau’s Omona Wapi, where 0:19-0:52 of the lead “Lisanga Ya Ba Nganga” is mostly Rochereau and his men, first chorale and then a solo turn, and irresistibly beautiful in my opinion. As is the whole track, come to that. The winner so far.

Do you consult with any other critics when compiling your year and decade-end lists? Carola included. — AJ, London.

Of course I do. Why not, it’s something to talk about as the year ends, and when I was at the Voice I did it all the time. These days, however, I converse regularly with very few critics, Joe Levy mostly. I also check out unfamiliar titles on lists published in December. But I always have an excellent preliminary database because I’ve not only reviewed and rated most of the likely candidates but put them in rough Dean’s List order. So over the years most of my calculations have involved relistening and finalizing that order, which does move around quite a bit in December and January. And always there’s input from Carola, who doesn’t consider herself a critic but whose comments on what’s playing in the dining room color my writing every month of the year.

I’ve been beguiled by your use of the term “formalism” in reference to bands and artists. In a general sense I can grok what you are saying but am wondering does the use of the descriptor formalist connote a sense of stylistic predictability or derivativeness? Is there an antonym in your critical arsenal for music that is the antithesis of formalistic? Below are a couple of abridged examples. It appears so often, and isn’t necessarily correlated with whether you find something pedestrian or worthwhile. — Martin Cassidy, Nashville

Van Halen: Van Halen II [Warner Bros, 1979] So how come formalists don’t love the shit out of these guys? Not because they’re into dominating women, I’m sure. C+

R.E.M.: Fables of the Reconstruction [I.R.S., 1985] But as formalists they valorize the past by definition, and if their latest title means anything it's that they're slipping inexorably into the vague comforts of regret, mythos, and nostalgia. B+

Let me note to begin that the “they” in the Van Halen needs a clearer referent, a fuckup on my part—no telling whether it indicates the band or the formalists. I meant the band, thus suggesting that formalists may be clever, aesthetically sophisticated fellows, but they’re probably just as sexist as the metal clods they disdain. And that’s a start: formalists are aesthetes who may well be jerks in other respects and often lack the idiosyncrasy that makes pop music feel special. What do Van Halen and R.E.M. share? Both are technically brilliant bands that delight in recapitulating the musical essentials of their chosen genres, metal and folk-rock/indie-rock. That much only a bigger clod would deny. In Van Halen both Eddie Van Halen and David Lee Roth take their respective roles to new levels, just like R.E.M.’s guitar polymath Peter Buck and charismatically elusive Michael Stipe, whose early refusal to pronounce the band’s lyrics said so much it didn’t actually come out and say—that their collegiate following didn’t actually care what the songs were “about” because the songs’ sound was all that mattered to them. Preferring R.E.M.’s materials to Van Halen’s and noting both that I warmed briefly to Van Halen when 1984 led with the great single “Jump” and that Stipe soon abandoned his mush-mouthed shtick, which in retrospect was what it was. But this isn’t to say formalists can’t be fun. My favorite example is Zion, Illinois’s Shoes, who I don’t recall even touring (though they did release a live EP). Basically, they just made records. And you could make a case that the Ramones were the greatest formalists in rock history. But after venturing that in relatively modern pop music it’s a special province of power pop I’ll say sayonara to a question best answered by a book no sufficiently smart person is likely to write.

Re: Ray Davies. Have not seen much, if any, reference or opinion on him in your review or other writings. Would really appreciate your thought on his writing with the Kinks and solo.

Thank you.—Frederick Bulman, Athol, Massachusetts

P.S. Your comments regarding Chicago and World Party made me wince.

This question addresses another great ‘60s bands that did its best work before the Consumer Guide got started. (Personal to Creedence questioner: so to an extent does yours.) I did actually publish a Kinks piece when I was just getting started at the Voice in early 1969, and it’s OK for something I wrote overnight, as I did at the beginning there because post-Esquire I resented my $40 fee. And I paid a lot of attention to them when they moved from Reprise to RCA and commenced a theatrical phase that I never thought jelled, though at times I admired it. (Dave Hickey did a great review of one of their shows for me.) So let me say first of all that I love the Kink Kronikles comp and then add that Ray Davies wrote two of the greatest songs in rock history: “Waterloo Sunset,” a clear candidate for number one, and “Lola.” But I’ve never been sold on the RCA stuff and stand by the reviews I published except to say that some of the B plusses may well just have been B’s. Basically, I think Davies has the terrible politics/worldview of a professional nostalgiac even though only such a nostalgiac could have written “Waterloo Sunset,” which bottles up and decants the respect and affection due a past that deserves plenty of both. He regards himself as some kind of satirist or public observer but too often he’s soft in the head. I’ve listened to some of his better-received recent stuff and didn’t think it was terrible. But though I did try, I didn’t think it was compelling either.

P.S. My Chicago and World Party reviews were supposed to make their fans wince. Glad the trick worked.

Bob: Could you tell us a little bit more about your relationship with hip-hop at the moment? I’m interested in how you decide what to write about these days, given the vast and ever-expanding universe of new music in the genre. Are there writers or publications you read regularly who keep you clued in? Do you struggle to keep your ears fresh, a problem that seems to affect a lot of longtime hip-hop followers given the radical changes (geographical, cultural, technological) the music has gone through over the last few decades? Are there subsets that interest you or speak to you more than others? Trends or sub-styles you find yourself gravitating toward or being put off by? I think you’ve written so well about so much hip-hop, and I would never want you to trade your idiosyncrasies for a more programmatic approach. But sometimes I wonder how, for example, Serengeti gets so much ink, and Drake so little? — Richard, Atlanta

Except for Pitchfork a little and to an even lesser extent Rolling Stone, I don’t look anywhere for hip-hop advice. That includes the New York Times, where I’ve found Jon Caramanica’s numerous discoveries of so little personal use that even when I do check one out the intent is basically informational—two plays max, usually one. I’ve written here before about my informed skepticism in re Soundcloud rap and how much I’ve come to hate the word “bitch.” I do check out most high-charting hip-hop albums but seldom get to play three. Moreover, hip-hop is a singles music more than ever and I review albums; hip-hop is video-oriented and I haven’t paid attention to music videos in well nigh thirty years. Even so I write about a lot of hip-hop for a 78-year-old white guy, just not at the same clip as when I was a 48-year-old white guy. I seem now to be one of the few critics to pay much mind to alt-rap, which has obviously lost what veneer of hip it ever had. So if it’s somebody like Serengeti, who puts out a shitload of music much of which is to my ears at least engaging or interesting, I make my report, while though people have been telling me Drake is a pop god for years—my NYU students loved him—I’ve decided again and again that he’s a pop bore. As in most music these days, I pay more mind to female artists than male, not because it’s politically correct but because—statistically, far as I’m concerned—women are more excited about making music in almost every genre than men are, and have fresher perspectives to bring as well. That said, I find Buffalo’s Westside Gunn crew of interest and just wrote about two terrific EP-length Black Thought “mixtapes” that got extraordinarily little attention. At 48, he has an official solo debut album coming out on a major this week. About time. I’ll be on it.

The #1 reissue of 2020 will probably be The Harry Smith B-Sides due October 16, a four-CD box with the flip side of every 78 Smith included on his Anthology of American Folk Music. The box was years in the making but since the events of this summer, the producers chose to omit three tracks due to racist language—Bill and Belle Reed’s “You Shall Be Free,” the Bentley Boys’ “Henhouse Blues,” Uncle Dave Macon’s “I’m the Child to Fight” (all on YouTube). All three songs feature the N-word in the lyrics. Do you agree with the producers’ decision and how does omitting those songs which feature the same language you’d hear on many rap albums differ from the decision made by Clear Channel radio during that debacle years ago, or the controversy regarding the music of Kate Smith or Michael Jackson or R. Kelly? I think the decision is the PC thing to do and I’m OK with it, but wonder what the Dean thinks. — LM, New York

In general I’m opposed to censoring history, and having checked out all three of these, only the Macon via YouTube, I think omitting them is a big mistake. These are very interesting songs. Uncle Dave Macon, who in my fuzzily unresearched recollection was less than any kind of racial progressive (as very few white Southerners were back then and all too few are now, which is not to make special claims for white Northerners), sending black people also ID’d as “farmers” south is singled out as proof of high cruelty, as slaves sent further south in the 19th century had always said. In “Henhouse Blues,” the C-word-that-rhymes-with-“moon”-not-N-word dreams of political success as a Black man only to further dream that—uh-oh, horror of horrors, maybe we should leave this politics thing alone—there’s a woman president. And the “You Shall Be Free” saga is amazing, more than I can detail. To sum up what I think I’ve found out, the melody was lifted from a Black spiritual. The Reeds’ version proved so fetching that unabashed tune thief Woody Guthrie recorded a rewrite called “We Shall Be Free,” which was then lifted by Bob Dylan in an “I Shall Be Free” that began its life on 1962’s Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan as mostly womanizing and often arrantly sexist but also, in a few of its many verses, quite progressively race-conscious; in later iterations it attacked or at least mocked Barry Goldwater. The Reeds’ version includes a stanza that goes: “Some people say a N-word won’t steal/I caught three in my cornfield/One had a bushel, one had a peck” . . . and then, I think (but can this be?), “One had a rope around his neck.” So what can that mean? Is the thief packaged ready for lynching, or has he recently escaped a lynching? Assuming that word is “rope,” one or the other is what makes the most sense, but only if you assume making sense is the intention; after all, in the Guthrie version I’ve been playing “N-word” becomes “preacher,” a great idea by me, and what I hear as the rope line turns into, Genius avers, “Other one had a roastin’ ear down his neck,” a much less great idea if it’s even accurate. Should we really be discouraged from pondering these imponderables by omitting the Reeds’ recording from this crucial archival reissue? Or is it just that mere record buyers may take the complications the wrong way? Sorry—I’m absolutely opposed whether my own account is useful or totally misses the boat, because either is possible and further investigation is called for. And as a PS I’ll add that when Black rappers use the N-word, they’re exercising legitimate claims on it that no white person shares. So that’s a bullshit point.