Xgau Sez: November, 2020

Some thoughts on family, work, dancing, and the permanent-collection CDs that come out at mealtime. Also: country songs about systematic oppression & screwing with the hegemony of classical aesthetics

Hi Bob. My name is Alfonso. I’m a 20-year-old student from Honduras. This is not a question but it seems to be the only way I can reach out you. I just wanna start by saying that I’m obsessed with rock and roll. Being obsessed with rock and roll, I stumbled upon you eventually because, well, you’re the most famous rock critic of all time. I was just reaching out to you hoping you see this and to tell you that I love your work. You and your writing mean the world to me. In a perfect world, I would be chatting with you about rock and roll. — Alfonso Godoy Baide, Tegucigalpa, Honduras

Well, this is cool. I don’t know if you’re aware that in 1985 I spent two months in Honduras with my wife adopting our daughter Nina, who we met when she was precisely two weeks old. Mostly we were in San Pedro Sula, and every afternoon after the rain stopped I’d walk around with her in my arms while my wife napped. I also walked further into the city by myself, and we left Nina with a sitter to take day trips up to Copan and over to the Miskito Coast. Our hostess was a Palestinian immigrant who owned a small clothing factory, and I understood that despite the cocks crowing and the iguanas darting about this was a genteel and protected neighborhood. But I never felt unsafe anywhere in the city. The last four days we spent speeding around Tegucigalpa with our lawyer to finalize the adoption. That was different. As you know, Teguce is the capital and also where the US anti-Sandinista operation was run from. It was cooler due to its elevation and where we were staying most houses were gated behind walls and armed guards were not uncommon. As you also know, I assume, sleepy San Pedro Sula turned into a cocaine hub, which was only one reason it also turned into a city controlled block by block by individual gangs, a city that by some metrics was the murder capital of the world. That’s why so many of the migrants Donald Trump and his racist henchman Stephen Miller stopped at the Mexican border came from Honduras and San Pedro Sula specifically. God knows what Biden will be able to do about it given the other devastations Trump left on his plate, but undoing the work of Stephen Miller will be a fine start.

Agree 100% on your assessment of Elizabeth Cook’s “Thick Georgia Woman” as a “classic in waiting.” So I am wondering if you have any additional comments about the phrase “dream genocide” found later in the song? Specifically, if the dream in question refers to MLK Jr’s famous quote, doesn’t it summarize the staggering cultural and personal consequences of 21st century racial bias in two deft and damning words? — Greg Morton, Blue Guy in a Red State, Idaho

I love Elizabeth Cook, adore that song, and wish I could agree with you. But the couplet in question, which goes “A feather down place to hide/For your dream genocide,” seems all too opaque to me, and when it comes to addressing racism—if that’s the intention, which I doubt—opacity is a sin. Fuck subtlety—the more explicit the better. Yet though I must be forgetting something—is there nothing of use in the vast catalogues of the manifestly good-hearted Willie Nelson and Dolly Parton?—I can think of only one explicitly anti-racist song in all of mainstream country music: Brad Paisley’s much-mocked “Accidental Racist,” where “caught between Southern pride and Southern blame” and especially “They called it Reconstruction, fixed the buildings, dried some tears/We’re still sifting through the rubble after 150 years” seem like the right direction to me even though the LL Cool J cameo remains an embarrassment. No longer mainstream is Jason Isbell, whose concise, powerful 2017 “White Man’s World” addresses many varieties of systematic oppression with a clarity that near as I can tell shut him out of Music Row, perhaps permanently. Kudos too to Mickey Guyton’s “Black Like Me,” which is a lot more explicit than any of the other exceedingly scarce Black country artists—Charley Pride, Kane Brown, anybody remember Stoney Edwards?—have dared. I hope the reason is fear of the base rather than fear of Black Lives Matter, though both are distressing. But I wouldn’t bet on it.

Your Dean’s List for the 2010s included two deluxe editions—M.I.A.’s Maya and Rihanna’s Anti. Are there any other deluxe or super-deluxe or “complete sessions” that you think improve on the original album release? For example, The White Album, or Nevermind, or Jack Johnson? Any thoughts on these big boxes in general? Thank you. — Rob Gallagher, New York City

There’s a difference between deluxe editions and the boxes you name. I often didn’t bother to check out boxes even when I got them in the mail, although I still wonder about that Grateful Dead one. But though I’m told I should check out the Jack Johnson and may some day, these expanded editions don’t really interest me. I’d much rather go dig out a Kirby Heard or Martin Creed album few know exists, or pay close attention to a Malian artist’s first U.S. release, than differentiate marginally between/among already established classics and register the existence of previously unreleased alternates and arcana. True deluxe editions, on the other hand, are worth a listen-hear. Since I buy most of my reviewables after streaming them on Spotify, it saves me bucks to check those out the bonus cuts, which are seldom worth the time or money but in the two cases you cite transform good albums into great ones. Often, however—a relatively recent example I examined carefully is Madonna’s Madame X—they have a diluting effect.

Hello Mr. Christgau. Your writings always read like you’re a person much more inclined to be looking towards the future than romanticizing the past and forgive me if you’ve answered this before: Off the top of your head, what is the oldest piece of recorded music you’re still getting a kick out of right now? — Julian Hartmann, Bonen, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany

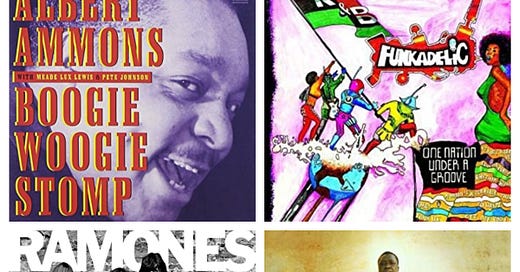

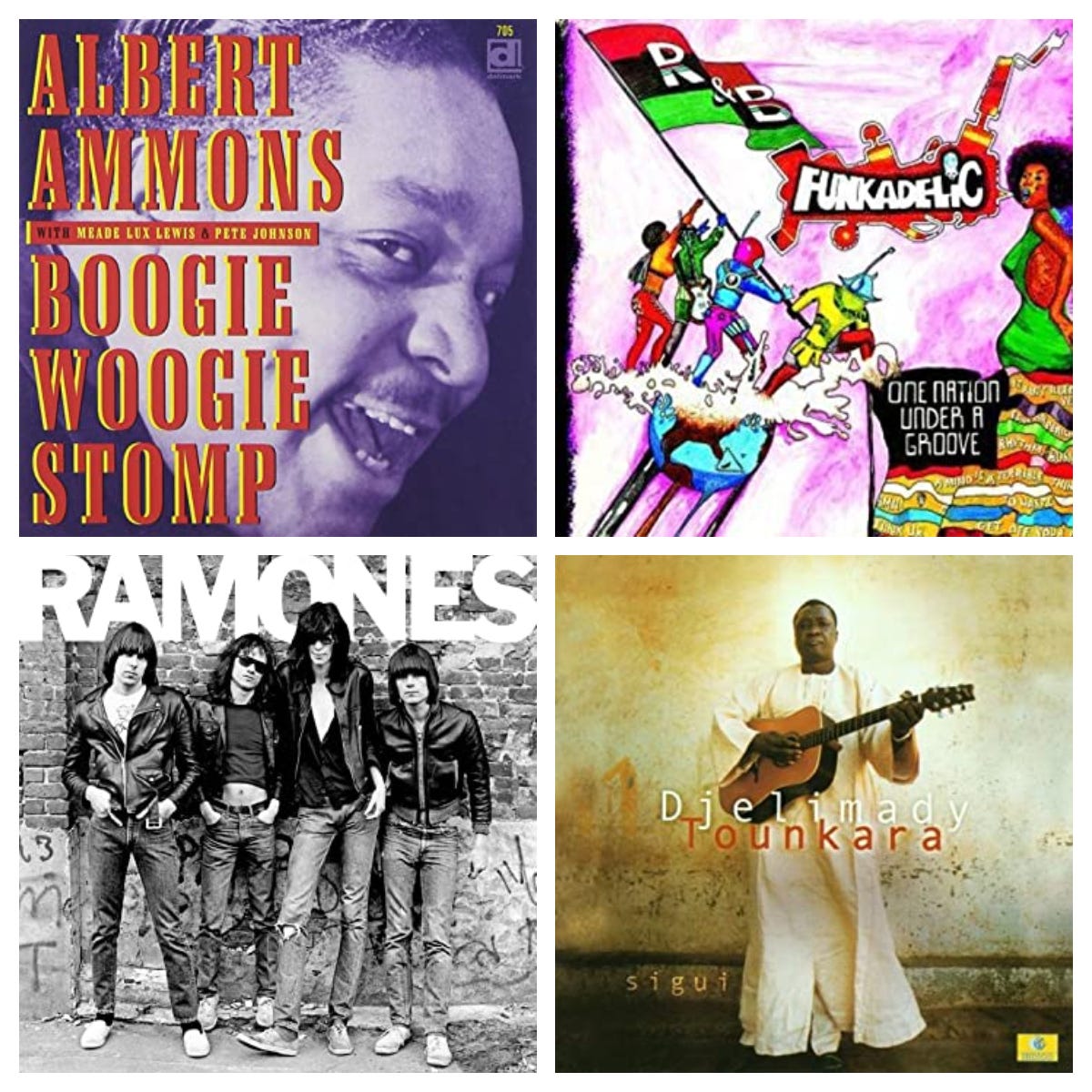

When I’m working, which is most of the time, I am indeed working, sifting through new stuff. But I play a lot of older music at mealtimes when Carola and sometimes Nina will be hearing it too. Looking over the permanent-collection CDs I need to reshelve at the moment, I see Albert Ammons, the Asylum Street Spankers, One Nation Under a Groove, Astor Piazzolla, the Ramones’ debut, Pretzel Logic, Billy Swan, Djelimady Tounkara, and Howlin’ Wolf. But that’s all post-World War II. From the ‘20s and ‘30s these days it’s less likely to be early Armstrong or Ellington, which I played a lot pre-2000, or Billie Holiday, an inexhaustible perennial, than country blues, particularly Skip James, who Carola’s really gotten into, the eternal Mississippi John Hurt (sometimes ‘60s stuff with him), or the superbly conceived and sequenced compilation Bernard MacMahon assembled for his American Epic project.

One of my teachers once said to me something along these lines: “Every other field has moved on, but aesthetics is exactly where it was 2500 years ago.” He was being provocative, but I can see where he was coming from. Do you see your criticism as aesthetics? Something else? Clearly we’re not just talking about beauty. There’s a Monk tune called “Ugly Beauty,” but is that just an evasion? Sincere thanks for this wonderfully generous online resource. — Tim Buckley, Melbourne, Australia

I certainly don’t see myself as an aesthetician. That’s a branch of philosophy, and while I took a few relevant philosophy courses in college and have dabbled around in aesthetics a little as any serious critic should, I’d rather immerse in art than in theory about it. But I have dabbled enough to know that in one respect your prof was setting you up for a fall. The key is that 2500-year crack. That puts us back with the Greeks, right? The Greeks had their Dionysian fling, as I discuss in the now finally unembargoed Dionysus essay that began its life with my long-ago Guggenheim world-history-of-pop project and took form as an EMP lecture prominently displayed up front in Is It Still Good to Ya?—but not as far up front as another repurposed essay from that collection, another EMP presentation that serves as a prologue: “Good to Ya, Not for Ya: Rock Criticism vs. the Guilty Pleasure.” Without going into any detail and thus steamrollering many relevant cavils and objections, just say this: the rise of Romanticism really put a crimp in the hegemony of classical aesthetics. One way of describing that crimp is to say that ultimately it valorized as beautiful various usages most classicists would believe were, like Monk says, ugly, thus reminding us that most of the Greeks who invented democracy were in fact snobs who denied citizenship to the lower orders. Without identifying with Romanticism except in the most general way, just say I’ve devoted my career and indeed my life to fucking that shit up. “Exactly where it was 2500 years ago”? Bushwa. (Most recent relevant book read is a tough one: Johann Gottfried Herder’s Song Loves the Masses. See also the Terry Eagleton and Marshall Berman essays that close Book Reports. The Raymond Williams too, why not? Go crazy. You asked for it.)

Did you know Slim Gaillard played an important role as musician and rapper in the fantastic 1941 dance sequence for Hellzapoppin featuring Frankie Manning and Whitey’s Lindy Hoppers? Did you know I met Slim Gaillard in London in 1988? I did not know he was half-Jewish—he didn’t look it. — Judy Pritchett, Montclair, New Jersey

I did not know any of these things, although as we are aware and my readers aren’t, I have known you yourself, the former Judy Rosenberg, since 1962. I’m also well aware that you became an expert on swing-era dancing in your forties and from the late ‘80s until his death a month short of his 95th birthday in 2009 were the companion and manager of the great lindy hopper Frankie Manning, who with your help I taught at NYU a few years back after deciding that my music history course was shortchanging the swing era (stuck the Boswell Sisters in there too). Here’s the Gaillard-Manning sequence you cite:

And here’s some more subdued Manning-Pritchett stepping in 1992, when Manning was 78: