Xgau Sez: June, 2022

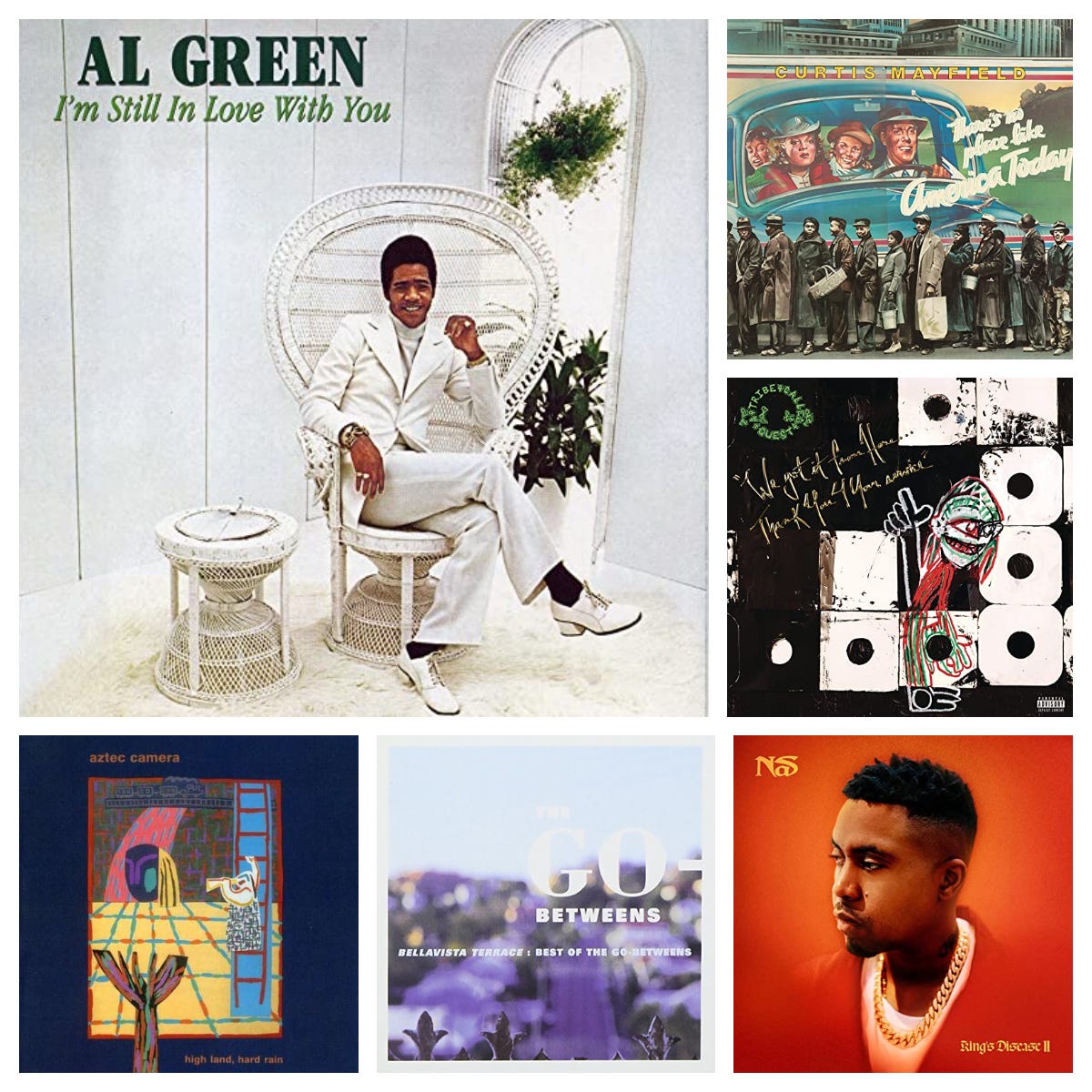

Standing by some old judgments; grade-grubbing Nas, Al Green, and A Tribe Called Quest; appreciating Billy Joel's attention to prose; and an encomium to the estimable C.D.

I ask this with respect for your intellectual and emotional engagement with records and artists of all stripes across many decades (including my beloved Wussy), and as a muso who excitedly read and re-read your Pazz & Jop essays and your Rock & Roll & columns in the Voice: Do your casual judgments of ‘70s Soul artists like Curtis Mayfield, Donny Hathaway, and Roberta Flack ever bother you in retrospect? Not so much the assessment of the music as the way you frame it—like Betty Davis as “the most overstated cartoon sex since Angelfood McSpade”? (Yes, I’m very familiar with the RL Crumb comics.) Particularly in light of the way Black American history has played out across the past several decades, isn’t there something a little “crime,” as my kids would say, about the white male Dean sitting in such casual, sometimes cruel, judgment of Black artists? — Pete Cenedella, South Orange, New Jersey

I’m certainly aware of this issue. But that doesn’t mean I feel any shame or guilt about what I wrote. My attitude in the ‘70s and ‘80s, after which I stopped writing as many pans as I had though the Turkey Shoots could be pretty insulting, was that it was my job to review all of popular music, including much more black music (which I’d now call Black because I recognize and affirm that that usage has changed) than any other generalist except Dave Marsh, because as I’ve written many times, almost all American pop music, especially post-1900, is part-African. But since I was often pointed and jocular about white rock, I saw no reason why I should treat Black music any differently—these too were commercially ambitious artists trying to sell their music to anyone with the shekels, and to protect them from barbs, to pretend that they were incapable of the same kind of failures of concept and execution that white musicians were, or that they didn’t sometimes grind out ordinary or weak product in hopes of selling it anyway, would be more condescending than disrespectful. As I keep saying, we like what we like, period. These days, when the Consumer Guide no longer makes any pretense to completism, I’m free to ignore both self-importance (no point getting in trouble by naming any offender here) and offensive content (the sexism and brutality that continue to be currencies in some of the hip-hop I don’t go for) of a lot of music I long ago might have felt obliged to pan. But I still think that Curtis Mayfield stretched himself way too thin and that Betty Davis was and remains overrated. I’m still bored by Hathaway and Flack. Nor are any of those judgments “casual”—they’re examined and ear-tested and and thought through. And by the way, I make it a principle not to censor myself—or simply avoid criticism—by removing anything I’ve published from my site even if I have regrets about it in retrospect.

Hi again, Bob. Hope you’re well. I ran across an article from January in the Atlantic, which was embedded in an article about the somewhat marginal Jack White and wondered if you’d read it, and if you had thoughts. The premise, statistically supported right or wrong, is that nobody listens to new stuff anymore; that the marketplace is deliberately stagnated by corporate types; that we should want to break out of that and maybe we will. It posits some theories about why everyone is just content to listen to Police songs and have zero interest in further expansion. You’re the guy who never stops searching—so, thoughts? Is it that there’s just too much stuff?? Thanks. — David Poindexter, Illinois

I value the Atlantic because it does some of the best political reporting and analysis in America, not because I pay much mind to its music coverage. Ted Gioia, who wrote the article you refer to, is a music historian of impressive breadth and appetite whose intellectual acuity is nothing special and whose heart is with jazz—see this review of one of his recent books that I wrote for the LA Times. To me it seems as if the stats he cites have a much simpler and less momentous explanation. First, people listen to more older music because every year there’s more of it. In addition, the way these things are categorized relatively recent albums are classified as catalog — almost all of all of streaming champ Taylor Swift’s 12 albums qualify as old music. Electrical recording is now just under a century old; what we might call hi-fi dates back to the rise of the LP circa 1948; pop became a “billion-dollar business” with the profusion of new product that boom generated circa 1971; crucially, digitization and then streaming made more music more available early in this century. There’s no question that recording artists’ revenues are down and will probably stay that way, so that most musicians will need to make their living on the road as they did through most of history. Whether that means that young consumers are hearing or indeed caring about less new music now than in say 2000 is another question altogether. Moreover, that older consumers are still listening to the music they grew up loving seems completely natural even if I get more sustenance myself by mixing in a lot of new stuff. And two more things. One, Gioia pays almost no attention whatsoever to hip-hop or dance music, both of which tend more innovative. And while he is especially interested in the venture capital the major labels put into new music, what I find significant is that music can now be recorded so cheaply and distributed so freely that a substantial chunk of what shows up in the Consumer Guide is DIY or close to it—stuff I learn about via various grapevines and online journalism.

After reading in your Lookback piece that you voted for A Tribe Called Quest for the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame this year (good on ya), I was wondering if you’d re-assessed their ‘90s classic The Low End Theory? I generally agree with your ratings, or at least can see where you’re coming from, but that one only being an honorable mention I’ve never understood. I love every track on the thing, it’s got some of Q-Tip’s and Phife Dawg’s best verses (“float like gravity, never had a cavity” is my favorite ever nonsense rap boast), and it builds to a splendid climax with “Scenario.” A plus by me. — Oliver Hollander, UK

I’ve been playing TCQ a fair amount since reading Dan Charnas’s J. Dilla bio and certainly agree that Low End Theory is more than an Honorable Mention, but back to back I still prefer their de facto postscript cum summum, the relatively slept-on 2016 We Got It From Here. So let’s just make it an A for the time being, OK?

Hi Bob, hope you’re doing well. Any reason why you didn’t review the last three Nas albums? King’s Disease II in particular was really good (he sounds more focused than ever since Illmatic), I’d love to know your opinion. Also: still no regrets about not giving Illmatic an A plus? With every new year that album sounds more like an A plus to me (and a lot of other people). Even a principled vulgarian such as yourself should hear that! And the same goes for Enter the Wu-Tang; if that’s not a A plus I don’t know what is. — Arthur Hendrikx, Brussels, Belgium

Actually, I did review two recent Nas albums in February, subscriber-only of course. There was a third I thought negligible and skipped, as I have many others—thinks a lot of himself, does Nas. As for Illmatic, A not A plus for me pretty sure. Since getting into the Wu-Tang Clan due to their Hulu bioseries I’ve been meaning to replay their debut album. Would be surprised if it didn’t sound like a full A. Would also be surprised if I thought it was an A plus.

Nas: King’s Disease (Mass Appeal ‘20) Showcasing the powers, pleasures, responsibilities, contradictions, and elephantiasis of the ego that accrue to so many hip-hop tycoons (“Car #85,” “10 Points”) *

Nas: King’s Disease II (Mass Appeal) Many hip-hop fans of a certain age consider Nasir Jones’s 1994 debut Illmatic hip-hop’s greatest album, and for sure the Honorable Mention I gave it in 1994 was way low. There was a leanness to his flow and timbre back then that the Pete Rock/Large Professor/Premier production honored and enhanced, and I admire how matter-of-factly unmoralistic lyrics from the Queensbridge Houses come to a proper climax with “Represent” and “It Ain’t Hard to Tell.” But that honest broker went what we’ll call conscious gangsta with the thuggier I Am . . . and didn’t regain his more humane voice until the mid 2000s trilogy Street’s Disciple/Hip Hop Is Dead/Untitled—a voice that hasn’t been approached again till this follow-up to its crasser namesake. I know I’m showing my age when I say EPMD, Lauryn Hill, and Eminem make it better and Lil Baby doesn’t. But if you suspect I could be right let me remind you that backloading the humane stuff is an old hip-hop trick: “Composure,” “My Bible,” and “Nas Is Good” provide relief at the end. And oh yeah—the bottom falls out on the so-called Magic he released just four months later, summed up by this Insecure Verse: “You’re top three, I’m number one, how could you say that?” B PLUS

I’ll bet you’re tired of grade grubbers but it’s driving me insane that I’m Still In Love With You is still an A minus even though you’ve put it in the same tier as Call Me. You had no problem with changing the grades for Call Me and Al Green Is Love so why not ISILWY? If ever there was an A plus album it’s this. Thank you. — Ted Fullwood, San Jose

I’m Still in Love With You is certainly an A not an A minus, and I can see making it an A plus. But note that the closing tracks that expand the CD version, “I Think It’s for the Feeling” and “Up Above My Head,” are both weak.

Do you have a favorite reaction from an artist to your negative review? — Dario, Croatia

Billy Joel reading or reciting a portion of my measured pan of I don’t remember what from the Madison Square Garden stage, assuming it actually happened that way—eyewitness accounts vary and memories do fade. Maybe he just named me, which would also be cool, but less so. Having my prose trumpeted to his masses would be a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. (BTW, I gave his GH 1 & 2 an A minus. What a crybaby.)

Sometimes I think about Carola’s uniquely effusive fondness for groups like Aztec Camera, or your shared adoration of Pretzel Logic-era Steely Dan. Or how she casually wrote the greatest-ever concert review of the Go-Betweens. Speaking as half of a great team, what do you consider your greatest distinctions—differences, I mean—as critics and listeners? — Erin, Austin, Texas

First of all, how did you know she liked Aztec Camera? Did she write about them and I lost it? But you’re right, she does, and definitely still did when your note gave me the idea of pulling it out recently. The biggest difference between us, I guess, is that her formal knowledge of music exceeds mine, which is one reason I respond more readily to singer-songwriters than she does—music as mere accompaniment to words she’s not necessarily focusing on doesn’t grab her. The other big difference, critically, is that she writes very, very slowly—that Go-Betweens review may look casual, but I guarantee without recalling any details that it was hard to write. One reason I assigned her Riffs is that I figured correctly that deadline pressure would speed her up. But one reason my successors in the editor’s chair assigned her pieces is that the results were invariably great and sui generis. A lot of her best music writing—cf. Go-Betweens, right, but also Cornershop, Latin Playboys, Fleetwood Mac, Guinness Fleadh, Reed/Smith, Steely Dan, Oumou Sangare, “Inside Was Us,” just to name stuff off the top of my head—was done post-1990. (All can be found on her site.) And then she got her teeth into The Only Ones and that was that for rock criticism except insofar as she remains my chief musical advisor, ahead even of Joe Levy. Usually I play archival stuff at meals, including a lot of jazz, though after I got her to read Charles Shaar Murray’s John Lee Hooker bio Boogie Man blues also became a deal—she was a bigger Hanging Tree Guitars fan than I was. But as deadline approaches I have permission to play “work music” and often sneak in stuff I want to know if she notices, whereupon I pick her brain and invariably learn something, often musical angles or details I hadn’t brought to the surface.