Xgau Sez: January, 2021

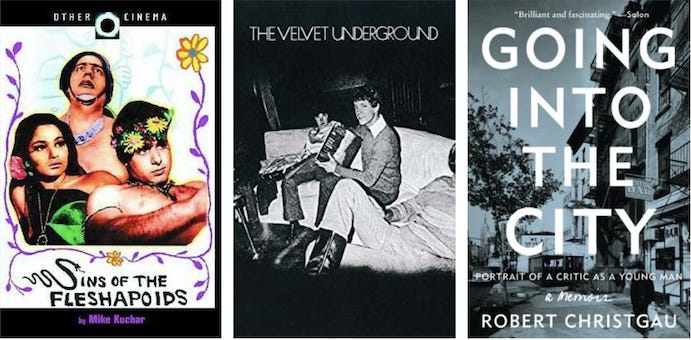

Going underground with movies and the Velvets, saying yes to sampling and no to Sidney Bechet and the War on Drugs, and putting "Brown Sugar" out to pasture.

I was delighted to read in Going Into the City of your experience with Lenny Lipton screening underground films in New York in the ‘60s. (And thanks for mentioning the wonderful Kuchar brothers.) That period and milieu of filmmaking is inspiring to me and I’d be grateful for other memories you could share. I figure you must have had contact with Jonas Mekas, although if I’m right your time at the Voice came after he left. This brings me to ask also about the Velvet Underground in their early days, since they were so involved with underground film. Were you aware of them during their circa 1965 Angus MacLise phase, when they accompanied film screenings? Or perhaps the Exploding Plastic Inevitable shows where the Velvet Underground and Nico played alongside Warhol’s films? — Andy Ditzler, Atlanta

Actually, I did rub shoulders occasionally with Mekas during my 1969-1971 freelance tour with the Voice, but only because he knew me from the Popular Photography story my high school pal Lipton assigned and I interviewed him for, as I should have. He was the kingpin of that world and a genuinely remarkable man in many ways, but not one who had much use for me once my pop proclivities were on the table—he had no interest in “movies” at all. So while I was happy to help Lenny run the Eventorium’s Friday-night film series up on West 100th Street, and sat through many hours of experimental cinema from Stan Brakhage (always interesting, occasionally great) to Gregory Markopoulos (horrible and subsequently withdrawn from the so-called New American Cinema canon and indeed circulation by the egomaniacal Markopoulos himself) because underground movies did continue to interest me, it was the New American Cinema’s meager pop wing I wrote about: in particular the Kuchars, who remained friendly with Lenny after they all relocated to the Bay Area, and Stan VanDerBeek. My first glimpse of the Velvet Underground was at a St. Marks Place club called the Electric Circus, I believe under a Plastic Exploding Inevitable rubric that featured the whip-dancing of Gerard Malanga, who didn’t impress me (at all). I think this preceded the release of their first album, which took me a while anyway; it was album three that truly converted me. I witnessed their legendary 1970 Max’s run multiple times. Lenny, who became a successful inventor specializing in stereoscopic imaging, remains a friend although not a close one; a photo of me he took when I was 20 has appeared on this site. I hope to see him the next time I get to Los Angeles, which I hope is relatively soon. Knowing someone for 63 years is worth celebrating, believe me.

What would you say to an older musician if they were hesitant about giving permission to a younger artist who wants to sample their music? — Zach, Washington, D.C.

That obviously depends on many things—how prominent the sample is, whether or not the originator of the music likes the way it sounds in its new context, and what your commercial ambitions and prospects are, to name just three. At the very least you can offer to acknowledge the sample in your packaging and agree to give him a small piece of whatever profits ensue from the recording, which these days are of course negligible much more often than not but you never know and the originator probably knows even less. Plus you should argue that sampling is a practice that has real artistic merit, recontextualizing both new music and the musical history sampling explicitly acknowledges. I miss it terribly myself—a big reason trap generally fails to reach me. I wrote a piece about sampling that’s never been collected, though I regret not shoehorning it into Is It Still Good to Ya?

One musician you’ve never reviewed was New Orleans clarinetist Sidney Bechet. With his improvisational prowess and warm tone, I would think that an Armstrong fan like yourself would have recommended one or two of the albums in his immense discography. Is his singular style of music not in your wheelhouse and if not why? — Sam, Ridgewood, New York

I’ve asked myself this question for years, gave up on the four-CD RCA comp The Victor Sessions: Master Takes 1932-43 a while ago but still spun the single-disc Ken Burns Jazz once in a while. This I’ve done three-four more times since your question arrived, but still concluded that for someone of my musical education his soprano sax was not distinctive enough sonically, improvisationally, or conceptually to demand my attention. Not that I’m skeptical of his reputation; far from it. And the music sounded pleasant enough. To double-check, I made sure Bechet was also within earshot of household jazzbo Carola Dibbell, who has intensified and helped articulate my response to Coltrane, Davis, Rollins, and Reinhardt, among others. So this morning before I sat down to write I asked whether she noticed the old jazz I’d been playing and she told me she had. So why hadn’t she mentioned it, as she so often does? “I thought it sounded good, but not stop the presses.” So that’s probably it for that.

I admit to bias but could you re-review War on Drugs and Kurt Vile and the Violators at some point? I remember one comment you made on Granduciel’s songwriting and something about KV with CB but that’s all. They are both incredible live bands and all-around great supporters of the scene here in Philly. — All Best, Chris

Sorry, but I’m not going back there. Retrospectively, I figure the War on Drugs to be in a class with the 1975, an even more admired band I have no use for either. And Vile I’ve tried and tried with—as with Guided by Voices, that’s the seminal example, he’s a revered songsmith whose oeuvre has never made the slightest dent on my auriculum. Both may well be great live bands and scene stalwarts, but as a stalwart of that scene yourself you’re more prejudiced than I am, because those songs have had a very different kind of chance to dent your auriculum. Enjoy if you like, more power to you—people like what they like, that’s fundamental. Courtney Barnett obviously did, and must have helped in some way you’re better equipped to suss out than I am:

Courtney Barnett and Kurt Vile: Lotta Sea Lice [Matador, 2017]

Fetching guitars, nice goofy vibe, songwriting dominated by spaced-out drip Vile rather than Barnett’s distracted depressive (“Over Everything,” “Continental Breakfast”) **

As for the War on Drugs, here’s my scholarly commentary in an interview I did with Dan Weiss at Spin to promote Going Into the City. I’m the first speaker:

What do we make of the War on Drugs? What the fuck is going on? Why do people adore this? I’m asking you here.

I’m thinking now that I have the time [to replay it], we’ll see how that goes, maybe it’ll go well, it might really be tough. But I was thinking of doing a week where I just do the War on Drugs and then, what’s her name, FKA twigs. I’m not actually convinced that those records are as . . .

Bad as they seem?

Skimpy as I think they are. I mean, I haven’t gone to that level yet. War on Drugs sounds like, I mean, has anybody else said it’s blanded out U2? That’s what it is. Has it been compared to U2?It’s been compared to Springsteen and Tom Petty a lot.

That’s ridiculous! That’s fucking ridiculous! I mean, Tom Petty writes real lyrics. And so does Bono, don’t get me wrong, but not the way that Springsteen and Petty do. This guy, whatever his name is, can’t write lyrics at all. He can’t write fuckin’ lyrics! You know that’s a very important part of a musical gestalt. It’s like if Springsteen or Petty buries his lyrics . . . boy, that’s nutty.

I am curious, what is your typical interaction with music when you write about music? Do you play your writing object in the background, or keep the environment quiet but just pull out moments that will help with your writing, or even play something else in background? — Minghan Yan, New York City

As I believe (and hope) most critics do, I almost invariably play whatever I’m writing about as I’m writing. You never know when some error will reveal itself or some new idea pop up—plus it makes it easier to use the remote to pin down or double-check a crucial detail.

I’m curious to know your thoughts on the Stones’ “Sweet Black Angel,” and if those thoughts have changed over the years. The irony of tracks like “Brown Sugar” is pretty obvious, but “Sweet Black Angel” in particular, with Jagger’s enunciation and usage of the n-word, has always baffled me. Just wondering what your take on this is. — Jeremy, Missouri

Politically and every other way, I find “Sweet Black Angel” far more attractive in retrospect than “Brown Sugar,” which I decided should be put out to pasture after I saw Bob Dylan cover it in 2003 and (less problematically, I admit) the Stones themselves roll it out at a 2005 concert. Irony be damned, its representation of cross-racial master-to-slave lust is far too realistic—too easy to interpret one-dimensionally as an explicit and unembarrassed articulation of a specific variety of lust. N-word or no n-word, “Sweet Black Angel” can’t be misprised that way even if you’re not fully aware that this “angel” is in fact a historical personage: the crucial Black feminist radical and indeed Communist Angela Davis. As the song presents her, this woman isn’t in anybody’s bed. She’s in a court of law even if you’re not hip enough to know every detail—a star-level celebrity whose picture is worth hanging on your wall whose freedom is in jeopardy as a result of the peril her Black brothers still suffer. The Genius transcription is a mite sloppy, but the Genius commentary isn’t: “one of the few overtly political Stones tunes.”