Xgau Sez: August, 2020

Life with (and without) cats, some thoughts on the back catalog of James Brown (and Sinatra and Nat King Cole), Lady A versus the schlocksters, born again Dylan versus born again Kanye

Your wonderful post about The Zoo compelled me to finally pose this quite personal question. As far as I’m aware, nowhere in your canon have you ever mentioned having pets. Perhaps your living situation entails preventative rules, but since relationships with animals can be as profound as those with human family members, it’s almost odd to imagine you never having enjoyed one. Any such stories from your love-filled life? — Erin, Austin, Texas

I had two cats as a child, neither of whom my mother, in most respects an exceedingly kind woman, would let sleep indoors. The first, a petite brown-and-white female called Taffy, was evicted and left in what my mother swore was “a good neighborhood” after gifting us with a dead bird on our back stoop. The second, a sleek gray male I called Pussycat so some cozier name wouldn’t endear him to me, figured out the score and ran away twice, breaking my heart anyway, especially since I’d actually gone out and found him the first time. Carola, on the other hand, had at least 40 cats as a child including Crazy Baby, who went into labor on the dining room table one Thanksgiving. It was from two different litters in Carola’s childhood abode that in early 1974, around when we began trying to conceive a child, we selected tiny gray Jane and bolder black Enterprise. Both were still with us when we adopted Nina in 1985, but by 1988 both had died, which Nina noticed and cried about. So for her fourth birthday we adopted a brother-sister pair. The exquisite, eccentric tabby female we named Orko (the androgynous sprite in Nina’s beloved She-Ra) after she proved no Janeen (the intrepid secretary in Nina’s beloved Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles), whose life Carola saved by discovering she would eat delicatessen turkey. The orange male we imagined as a red-headed German butcher and named Oscar. (At left above, clockwise from bottom, are Oscar, Carola, Orko and Nina.) Carola was very fond of Orko even though she liked to jump onto the bed and block Mom’s nostrils with a paw to wake her up. But in all her multifelineous life, Carola has never met a cat she admired as much as Oscar, and neither, obviously, have I—not only was he perceptive and affectionate, nuts about mushrooms and good to his nutty sister, but he would let you scratch his belly and then salute you by passing his right paw over his eyes. The day we took him to the vet to be put down at 18, I lifted his wasted body to the bed and scratched his belly and he saluted me one last time. About two years later, a wobbly but still exquisite Orko expired on the floor. Feeling we’d never top Oscar, plus vacation sitters were getting harder to find, we’ve been catless ever since. But in December of 2016, in the only good news I can recall from that awful month, Nina took in brother-and-sister rescue kittens: agile, brilliant calico Cinnamon (above, right) and big, goofy, attention-craving tuxedo Kirk—the names they came in with, though the Kirk-Enterprise pairing is notable. Nina has proven both a fine portrait photographer and a devoted mother, once rescuing Cinnamon from a fire escape a floor up in the dead of a rainy night. Carola and I call them the grandchildren.

Starting with the Star Time box, the James Brown reissue program of the ‘90s was so revelatory and exciting so first let me thank you for turning me and I’m sure many others on to his amazing music which might not have gotten our attention otherwise as white boys. So my questions are why did you stop reviewing his albums in the late ‘90s (the last one you reviewed was his Say It Live and Loud concert) and do you recommend any of the four later releases (Dead on the Heavy Funk, Ballads, Love Power Peace, Funk Power 1970)? — Ed Stephens, New York City

At a certain point sorting out JB comps became too much work, especially since I had nowhere to write about them—my annual Xmas best-of roundup in the Voice had plenty of other fish to fry, and after I got canned there such detailed breakdowns weren’t appropriate for the venues that were paying me. There was one partial exception, however: the James Brown obit essay I did for Rolling Stone Christmas week of 2006. That’s reprinted in Is It Still Good to Ya? and hence embargoed until November of this year. But the credit line says “Substantially revised” for a reason—that essay was used as the basis for the rather different JB piece I wanted to preserve in my collection. Hence two discographical grafs were deleted from the RS piece, and for what they’re worth, here they are:

Loving the box and two or three live ones, you'll wonder how to proceed. Many of the glorious reissues of JB’s CD-era revival—Dead on the Heavy Funk, Roots of a Revolution, Soul Pride: The Instrumentals 1960-1969, Messin’ With the Blues—are now available only used from usurers; the matched 1996 Foundations of Funk and Make It Funky double-CDs vary Star Time for fans who want funk to the exclusion of r&b and soul; most of the renowned In the Jungle Groove is also available in briefer form on the box, making it for serious students only even though Brown is the rare artist who improves with length. But the finest of the classic comps remains: 1988’s Motherlode, where Cliff White exhumes the unreleased “Can I Get Some Help” and rescues the head-on nine-minute “People Get Up and Drive Your Funky Soul” from the Slaughter’s Big Rip-Off soundtrack. The string syrup saturating much of the useful recent Ballads collection isn’t ruinous, and soon enough Dave Matthews and Pee Wee Ellis chip in some funk and Brown has turned Porgy into a woman protecting a guy who’s getting manhandled by the cops. The choicest of the many sidepeople collections is the thoroughly enjoyable Pass the Peas: The Best of the J.B.’s, which establishes that when James himself is announcing “Gotta have a funky good time,” said good time seems incalculably more necessary. The only recent best-of I play is the second JB volume in Universal's budget Millennium Collection series—’70s masterpieces surrounding an embarrassing add-on called “Down and Out in New York City,” it’s perfect for vacation travel.

James Brown could be embarrassing, absolutely. Arrogant. Self-deluded. Coming up in an r&b business where the only way he could get King Records’ Syd Nathan to cut Live at the Apollo was to pay for it himself, he inherited the hits-plus-filler theory of LP production, and the few JB studio albums that hold up as wholes are hard to find. So much of the superb There It Is has been recycled that it’s hardly missed, but for the silly Hot Pants to pass to the usurers is a serious matter, and long-lost King product like Super Bad and Cold Sweat never reached CD outside of Japan. A few oddments remain, however. Gettin’ Down to It, a what-the-?? piano-trio record from around the time of “The Popcorn” that transforms “Cold Sweat” into cocktail music and “Time After Time” into funk, will pique Ballads fans. The all-new material on 1998’s I’m Back is pretty damn funky for a 65-year-old some say was 70. And then there’s 1973’s The Payback, which probably remains in print because hip-hoppers like its aura of blaxploitation, although Brown’s revenge fantasy never made the flick it was written for.

A few months ago, there was a question here asking for your thoughts on ballad singers Dean Martin and Bobby Darin and you responded by saying you didn’t care for either of them preferring Sinatra and many black pop singers starting with Nat King Cole. You’ve already written that your favorite Sinatra albums are Songs for Swinging Lovers and Nice ‘n Easy so I’d like to ask where to start with the best Nat King Cole albums? — Harry M, New York

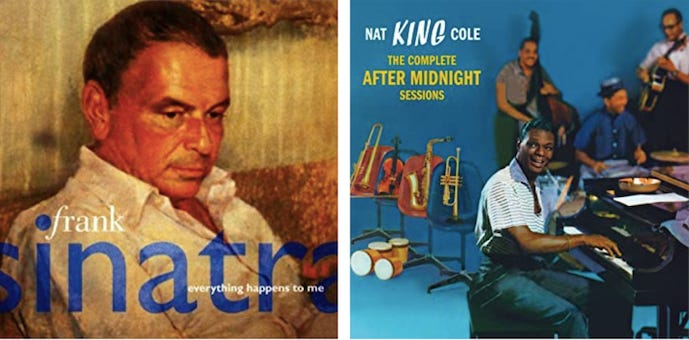

First of all, I would definitely add to my Sinatra A list In the Wee Small Hours and the late, deliberately creaky, self-selected old-man compilation Everything Happens to Me. As for Cole, well, as with Clapton a while back whaddaya know? An essay on Cole, written in 1992 and called “Across the Great Divide,” leads my highly non-online 1998 Harvard University Press collection Grown Up All Wrong. You probably want two Cole collections, one of the ‘40s piano hipster and one of the pop smoothie nonetheless capable of 1948’s surpassingly strange “Nature Boy.” For the hipster: Rhino’s Jumpin’ at Capitol or conceivably the even jazzier Complete After Midnight Sessions. For the great crooner: probably the much spottier 2001 double The Nat King Cole Story, which like 1998’s The Greatest Hits and 2005’s The World of Nat King Cole I got for free back in the good old days and can’t advise offhand on duplications etc. But one of each will certainly be a start.

You are a self-described fan of married life and the dynamics that go with it, which you relate in honesty and truth. As a newly married man myself, I enjoy reading on what’s ahead, and am willing to get excited for the concept as I was willing to get excited about the music you so eloquently wrote about in the ‘70s CG columns. Is your appreciation of a musician’s work colored by their domestic life? In particular, I think of Neil Young’s recent spousal tumult (I believe he left his wife of many years for a much younger woman he met on the enviro-protest circuit), and I’d be interested to know if this and/or other things have colored your perception of his music. Of course, every person’s choices are their own, but you’re a critic by trade and surely such a staunch defender of marriage, however difficult the road, that you would have something to say. With best wishes to you and your wife. — Robert, Prague, Czech Republic

This is a vast topic, so I’ll try to keep my answer as brief as practical. Recently I was asked to name some good marriage songs, and while Ashford & Simpson’s “Is It Still Good to Ya?” and I think Marshall Crenshaw’s “Monday Morning Rock” seem to have emerged from good marriages Etta James’s remake of Otis Redding’s “Cigarettes and Coffee” almost certainly did not—read her acerbic David Ritz as-told-to—and also, as I’ve indicated here, neither in many respects did John Lennon’s “Oh Yoko.” Nonetheless, Carola and I love them all equally as marriage songs, because the song is one thing and the singer is another. In so many differing ways, touring musicians do not lead lives conducive to domestic harmony, and that some should hold long marriages together anyway is a tribute to both the individuals and the institution. As for Young, he was married to Pegi for a very long time; they brought up a disabled child together. But Young is nonetheless an exceedingly eccentric and willful man, and I very much doubt his marriage would be much of a model for either you or me. It’s also worth mentioning that his new inamorata, dedicated environmentalist Darryl Hannah, was a legendary blond bombshell actress in the ‘80s—famously gorgeous. But she’s now 59. So at the very least this isn’t one of those disgusting trading in the old sexual partner on a brand new model things in which rich men regularly indulge. P.S. You want good marriage music from a man, I doubt you could to better than Brad Paisley.

What do you think about Lady Antebellum and the Dixie Chicks changing their names in light of the George Floyd protests? — Adam Montgomery, London

As a preamble, let me say that the heightened racial consciousness the protests reflected and inspired is the most positive political development in recent memory, perhaps the century depending on how the tax-the-rich thing goes, and that these details are small potatoes. That leaves me free to report that I’ve always considered Lady Antebellum a dreadful band/group/entity whose Nashville schlock was worthy of a name I’ve always considered a racist excrescence designed to appeal to the worst impulses of the country audience. So they changed their name 14 years too late, and then turned out to have poached the new name from a Black artist. As long ago as June, they were tweeting that this was all a misunderstanding, that “the hurt is turning into hope,” and the real Lady A, Black Seattle blues singer Anita White, seemed to concur. Now it’s August and the real Lady A still awaits what she regards as a suitable cash settlement or another name change by the schlocksters. Whatever she can wring out of the guys with the overpaid lawyers won’t be enough. As for the Dixie Chicks, well, I don’t want to get embroiled here in the endlessly complex blackface minstrelsy matter, to which I devote some 8000 words in Book Reports. But if they think just plain Chicks sounds better than Dixie Chicks—just aurally, sans internal rhyme—their failure to write more good songs than we who’ve rooted for them wished they would becomes easier to understand.

When you look at the current state of Kanye West’s career, do you see any parallels with Bob Dylan in the 1980s? A period where another great artist embraced rather disturbing political/religious/cultural views that were more notable than the terrible and irrelevant records he was releasing. If so does that give you hope that in time Kanye will similarly rally as Dylan did in the 1990s? — Josh Palmes, Stamford, Connecticut

No fucking way. Dylan’s fleeting romance with Christianity was infinitely less noxious morally. It was also fruitful musically where West’s “Christian” music is grandiose crap; if you’ll look back at my reviews you’ll see that Slow Train Coming was a B plus, his best album by me since Blood on the Tracks. Moreover, with the exception of his George Jackson song “George Jackson” and his Rubin Carter song “Hurricane,” Dylan’s retreat from politics dated back to the mid-’60s. His religiosity was nowhere near as pompous, self-aggrandizing, and devoid of any recognizable moral compass as West’s, and he would never under any circumstances have been so perverse as to embrace a fascist like Trump—unlike Neil Young, for instance, he never even dallied with Ronald Reagan—or become so addled he didn’t know evil when he saw it. Anybody can change, and West’s musical genius is on the public record. But so is a megalomania Dylan has never gotten near. He deserves to be stowed in a mental hospital, period — preferably a public one in, say, West Virginia.