In 1997, I got to review art critic Dave Hickey’s Air Guitar: Essays on Art & Democracy for The Los Angeles Times and thus write what may have been the first of its many raves. As some of you surely know firsthand, this episodic survey of the interface between aesthetic pleasure and market capitalism, both of which Hickey believes in, is a beloved book—scroll through its Amazon reviews and notice all the criticism fans buying copies as gifts. I have myself, and taught the book as well. NYU’s would-be bizzers studied first Chet Baker (“deserving the freelancer's ultimate epitaph: ‘If This Dude Wasn’t Dead, He Could Still Get Work’”) and then Liberace (“good taste is the residue of someone else's privilege”). Princeton’s would-be arts journalists read all 215 pages over the summer so they could discuss it at our first meeting, where we gravitated to “Simple Hearts,” about the magnificent Flaubert conte “Un Coeur Simple,” which like Hickey I discovered as a teenager and never forgot: the tale of an exploited, infinitely kind domestic named Félicité and her love for a parrot named Loulou, who Félicité envisions welcoming her to heaven as she breathes her last. Lest you suspect only politesse moved the Ivy Leaguers toward Flaubert rather than Liberace, Hank Williams, or wrestler with a line of patter Lady Godiva, I say they were onto something, just as Hickey and I were at their age. In this class, we agreed, we’d all promote our own parrots.

By then, Air Guitar had propelled Hickey into the higher reaches of intellectual celebrity when in 2001 he was awarded one of the MacArthur Foundation's huge no-strings “genius grants” for his “entirely original perspectives on contemporary art in essays that engage academic and general audiences equally.” Since the only painters addressed in Air Guitar are Paul Cézanne, politely slagged for deconstructing “the illusionistic image,” and Norman Rockwell, warmly defended from highbrow opprobrium, you might wonder how much his hit book had to do with the “contemporary art” he made his specialty. But Hickey just took it as it came. A lifelong swashbuckler who’s always disrespected academia but also makes it a principle to do what he has to do, he coolly held onto his day job at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, a city he was happy to call home even after its casinos relieved him of a chunk of his grant. By 2010, however, first the UNLV English department and then the UNLV art department had had it with his art-world celebrity and polemical chops. So he moved to Albuquerque with his wife, Libby Lumpkin, a curator and academic of some notoriety herself, who long after inspiring the Julia Roberts character in Oceans 11 landed a tenured position at the University of New Mexico.

Almost 70 by then, Hickey arrived with a U.N.M. teaching job he soon put behind him—his marital partner had tenure, after all. But he never stopped writing and curating and gadding about, and eventually emerged two more collections. I like both these books: 2013's Pirates and Farmers, which I understood quite well not just because I knew he was fine with “good farmers” like me but because it applied the same acuity, wit, and rhetorical flair to the art world that Air Guitar did to the wider culture (try “Nurturing Your Addictions,” a brutal takedown of what happens when art meets grad school, or “In the Sunshine of Absolute Neglect,” on a collection of Ghanaian movie posters), and 2016’s 25 Women, which I understood barely at all because I knew none of the artists it celebrates, yet read eagerly anyway not just for the aphorisms (“paintings are utterances, like birdsong, but they are not language, and they are not texts”) but for verbal proof that Hickey sees, physically, the way a great bass player hears, experiencing every sonic detail of the music in the room as he or she transforms it for the better. But many readers noticed something else about 25 Women: that much like Libby Lumpkin in her 2005 collection Deep Design, Hickey refuses to categorize these female artists he admires in terms compatible with feminist notions of identity. So 25 Women was when a major chunk of the institutionalized art world joined Hickey’s bosses at UNLV in crossing him off their list.

To our immense good fortune, this didn’t stop Hickey from publishing another collection in 2017, one explicitly conceived to follow up Air Guitar: Perfect Wave: More Essays on Art and Democracy. Not so good is how many editors and readers could care less—the book’s few positive notices ran in such periodicals as PopMatters and Rain Taxi, and where Air Guitar generated 50 customer reviews on Amazon, Perfect Wave snagged two. This is both sad and ridiculous—insofar as the newer book is inferior, and I wouldn’t swear it is, the differential is nothing remotely like 25-1, reduced surprise factor or no reduced surprise factor. But there is one big difference between them. Air Guitar is dominated by self-assigned and -generated monthly columns Hickey wrote for the L.A.-based monthly Art issues, where he was edited but ran his own show. So in some respects it’s more idiosyncratic and “personal.” In contrast, most of Perfect Wave was assigned by quality slicks, particularly Harper’s and Vanity Fair, and there’s extra flavor in how irrepressibly and indeed “personally” Hickey honors and plays with the aesthetic strictures of the magazine piece.

Take the two most conventional assignments here, Harper’s’s “It’s Morning in Nevada,” straight reportage about a Las Vegas Democrat bringing her senatorial campaign to isolated Nevada desert towns, and Vanity Fair’s “The Last Mouseketeer,” which recounts a four-day exploration of Disney World. Road-tripping through a “Wasp-deprived,” “farmer free” Nevada where “the Middle American equation of agricultural drudgery and Christian virtue has no traction,” Hickey doesn’t explicate Georgia-raised Greek-American pol Dina Titus’s political positions. Instead he notices how affectionately she engages klatches of sixtyish seniors, how cannily she courts fans and foes of pupfish preservation and brothel laws, how efficiently she changes clothes in the back seat, and how prudently she filches cookies for the long ride home. The darker Disney report never disrespects the park’s exhausted parents and ride-drunk children (“nifty little creatures I had casually ignored my whole life because I had not enjoyed being one”) or the intricate, cornball mechanics of the park itself, in particular the animatronics he can't get enough of. But it does unpack the strangely ‘60s-ish aura of its “Tomorrowland”: “just another future that never happened, where the Jetsons live, where the Yellow Submarine plows the deep, and where we all have automatic butlers” when in fact we ended up in an “ever-expanding, ever-tightening grid of morally isolating niche markets.”

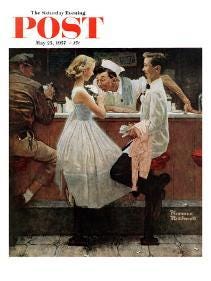

Where Air Guitar mocked the grotesqueries of leftwing academia insofar as it addressed politics at all, Hickey’s mercantile faith was so sorely tested by both George W. Bush’s callous Christianism and the economic elephantiasis of the art world that in these pieces and others Perfect Wave is almost frontally political even though it never gets to Trump. Thus it contextualizes Hickey’s complementary admiration of Michelangelo Antonioni (“isolating each fragment in a composition that insists upon the framed rectangle of the whole screen”) and Robert Mitchum (“a switchblade on a plate of cupcakes”); the furbelowed prose of patrician, “mad as a hatter” John Ruskin and the plain practicality of working-class, foundational architect Andrea Palladio; lesbian professor Terry Castle’s collection-as-memoir-as-“work of art” and the sad, cruel “self-repudiation” of “¡Una Lesbiana Enamorata!” Susan Sontag. And those aren't even best in show, my three candidates being “After the Prom,” which returns to Norman Rockwell with a formalist analysis of a 1957 Saturday Evening Post cover depicting a young couple, a soda jerk, and an Army veteran “in one of the most complex, achieved emblems of agape, tolerance, and youthful promise ever painted”; “Cool on Cool: William Claxton’s World,” which examines photographer Claxton’s many album covers to anchor what has to be the most profound and articulate account of West Coast “cool” jazz ever written (“Why have I never heard of this guy?” asked longtime Claxton fan Gary Giddins), and former Nashville songwriter Hickey’s borderline abstruse tribute to the Carpenters’ “Goodbye to Love,” which while analyzing the recording harmonically verse by verse folds in the assertions that “We have to assume that, objectively and quantitatively, some things are better than others” and “Nearly all of Nirvana tips its hat to Karen.”

Perfect Wave begins with “Baby Breakers,” about a very young Hickey who teaches himself to surf and nearly dies riding one of those perfect waves, all in the context of something that comes up a lot, his alienation from his jazz musician father and economist mother (who get a dedication in Air Guitar anyway). It ends with the peculiar “Little Victories,” which excoriates the devolution of both curating and lecturing while also lamenting that although his lifework has been analyzing “difficult art,” he’s best-known for 1993’s The Invisible Dragon, “Four Essays on Beauty” famed for its balls-out celebration of Robert Mapplethorpe’s sexually explicit and by many accounts perverse X Portfolio, and “a collection of narratives about popular culture”—that is, Air Guitar. Formally a postscript to “Art Fairies,” a devastating Vanity Fair report on London’s 2007 Frieze Art Fair that I recommend almost as warmly as I do everything else in Perfect Wave, “Little Victories” struck me as such a strange way for a collection of narratives about popular culture to kiss us goodbye that I called to ask him about it—I edited Hickey at The Village Voice in the ‘70s, and although I’ve only seen him once since then, we often talk on the phone. So is difficult art your true calling? I asked. I was relieved to learn that he’d changed his mind some since “Little Victories”: “I want to be known as an essayist.”

And that he is for sure, no less in 25 Women than in Perfect Wave but more accessibly and indeed relevantly in the latter. Christmas is coming, and Perfect Wave is the perfect way to surprise the criticism fans on your list. Impolitic though it may be to say so, it’s even better than Is It Still Good to Ya? and Book Reports.