The Ramones of Chicago Blues

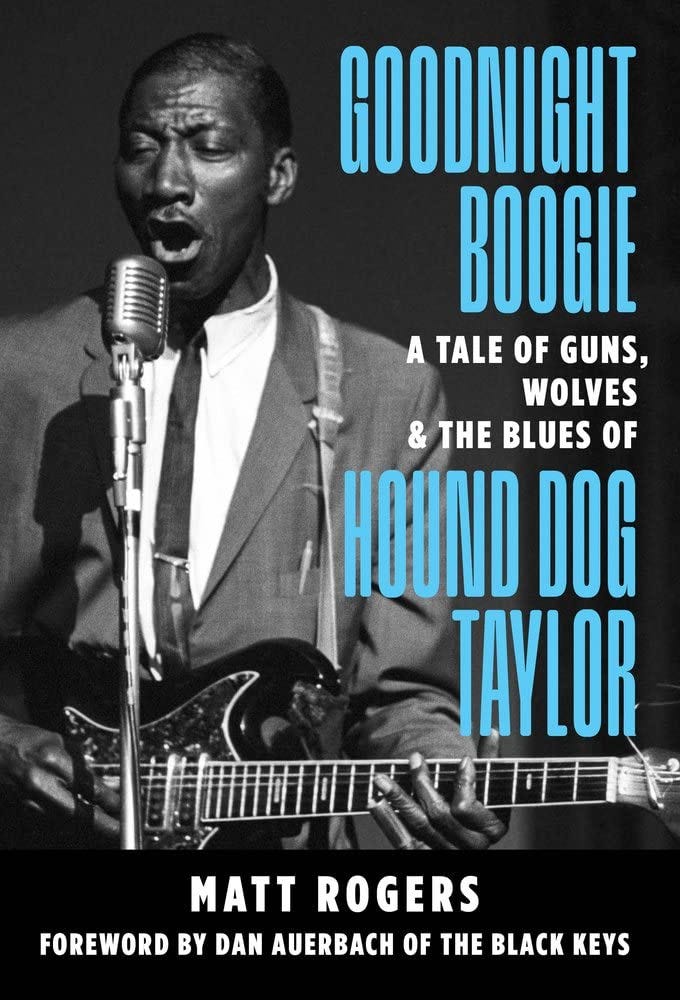

Matt Rogers: "Goodnight Boogie: A Tale of Guns, Wolves & the Blues of Hound Dog Taylor"(2022, 241 pp.)

Goodnight Boogie is one of the rare books worth reading foreword first, and not because Matt Rogers hasn’t done right by the text proper. Unpromising though his boilerplate billing as creative director of an “internationally-recognized” ad agency may seem, Rogers has written a terrific book. Pace and structure and narrative detail, first-person reporting, musical smarts, and sociological command all render it both meaty and fast-moving. But Black Key Dan Auerbach’s foreword establishes a tone. Such a big Hound Dog fan he named his daughter after Taylor’s “Sadie,” Auerbach has made it his business to get the right noises from one of the cruddy Japanese Teisco guitars Taylor did his filthiest Elmore James impressions on. “For someone who liked stuff that was really raw, and liked one-man bands, it was perfect music. It was unmanicured; it was ramshackle. I loved the way they dressed, too. They looked like absolute characters, in blue polyester suits, outfits like that.”

The story begins in 1942 in a north Mississippi hamlet where the Klan is hunting 27-year-old bluesman Theodore Roosevelt Taylor for having sex—in Mississippi, in 1942—with one of his white female fans. So after hightailing it through the woods and sleeping in a ditch, Taylor rode two buses to Chicago and started his life over. Jobs in the meatpacking industry and building television cabinets didn’t stop him from pursuing music wherever he could, which though he immediately switched from acoustic to electric guitar mainly meant busking on Maxwell Street. He also formed an unmonogamous lifelong relationship with a petite woman named Freddie Horne and became a full-fledged alcoholic, downing a fifth or so of Canadian Club on the daily. And crucially, he formed a musical bond with Brewer Phillips, a younger north Mississippian whose guitar of choice was a simple but classic Telecaster, the sharper edge of which both meshed and clashed with the dirtier sound of Taylor’s cheap Japanese job. Both were rough customers who fought regularly even before Phillips discovered a stolen guitar of his in the trunk of Taylor’s car. There were periods when they couldn’t stand to be in the same room together. But Taylor recognized that his unkempt music sounded better over Phillips’s rough-hewn sonic bed and Phillips recognized that Taylor projected a charisma he couldn’t muster. So their partnership, while intermittent, was lifelong.

Even so it took Taylor most of a decade to break through on a Chicago blues scene that peaked before he was a regular anywhere, a progress Rogers details while folding two crucial players into his tale: a bizzer and a fan, both white, which means they stood out at what became Taylor’s regular Sunday afternoon gig at Florence’s, a South Side bar with its own liquor store attached where every week Taylor, Phillips, and drummer Ted Harvey held forth pretty much nonstop from around two to around seven. Harvey he’d inherited from Elmore James, who’d died in 1963 at 45 claiming to have taught Taylor the same foundational “Dust My Broom” lick Taylor claimed to have taught him. A richer singer and more imaginative songwriter than Taylor whose unmatched Robert Palmer-overseen Rhino best-of The Sky Is Crying is still for sale and worth buying before it isn’t, slide master James remained Hound Dog’s closest musical relative.

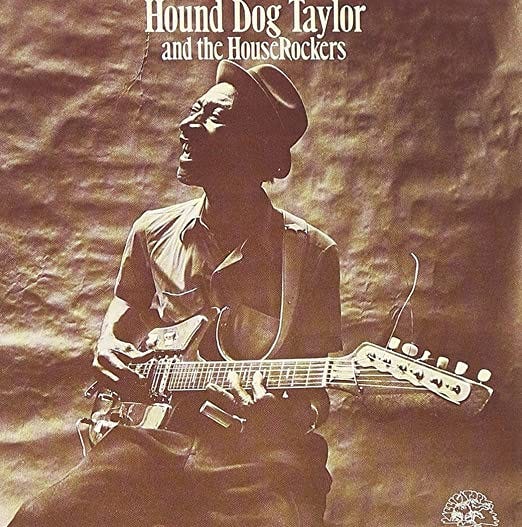

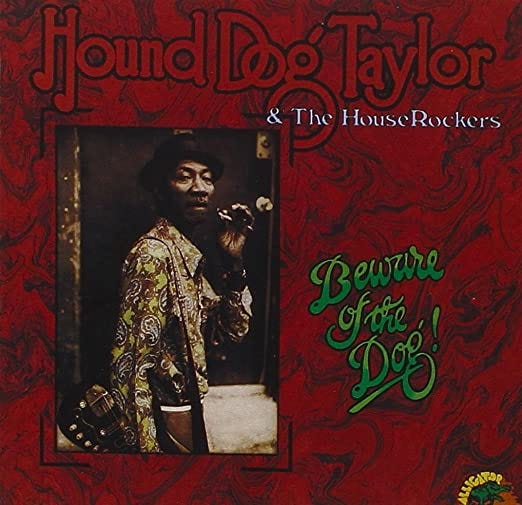

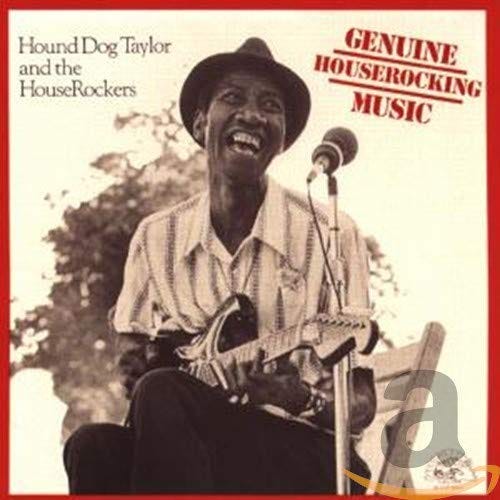

Superb though James was, however, he never delivered anything as raucous as the noise that rocked Florence’s every week after church. And pretty soon Bruce Iglauer, ill-paid adjutant of the great Bob Koester, whose Delmark label documented and dominated Chicago blues once the Chess brothers had cashed out, was a Sunday afternoon regular. And so was a young music nut from Wichita named Wesley Race, who Taylor began to regard almost as a mascot. Inevitably, the two young blues obsessives bonded at Florence’s, and before long Race convinced Iglauer to pitch a Hound Dog album to the more meticulous Koester, who turned the idea down. So instead the two impecunious twentysomethings went all but broke financing and producing 1971’s Hound Dog Taylor and the Houserockers for a new label Iglauer dubbed Alligator.

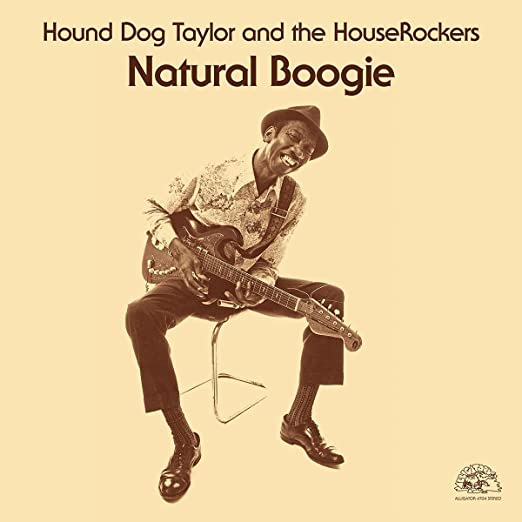

Unfortunately and indeed tragically, while Hound Dog lived 15 years longer than his homeboy Elmore, his time in the blues spotlight was much shorter—he’d die at 60, less than five years after his debut album was a surprise hit. Moreover, the “spotlight” wasn’t all that bright. I’m just about the only critic cited by name in Taylor’s book—“the Ramones of Chicago blues” and “a spiritual and cultural miracle” are the usual pull quotes, and I stand by both. Nonetheless, with Iglauer hustling and backing him up on his way to transforming Alligator into the new Delmark on the strength of Hound Dog’s kick-start, Taylor had four good years on the blues circuit. And though the book provides scant proof that the music press woke up to his singularity the way Rogers says it did, it does seem that college radio caught on in a way that turned Taylor into a viable club draw all over the east and midwest. His two appearances at successive Ann Arbor Blues Festivals were by universal acclaim knockouts even if one also occasioned a knockdown fistfight with Iglauer, who destroyed the camera Taylor had bought especially to take portraits of Freddie.

The following June Taylor and Phillips were sitting around the apartment Hound Dog and Freddie shared joined by Alligator up-and-comer Son Seals and a few other musicians when, as had happened so often before, the two bandmates started arguing bitterly once again. But when Phillips claimed to have fucked Freddie with Freddie well within earshot, this particular fight took an unprecedented turn: Hound Dog left the living room, came back with a rifle, and shot Phillips three times. An ambulance took him to the hospital, where his wounds proved less than fatal, although he was laid up for quite a while. Four months later Taylor, who had been feeling poorly and not getting it up the way he once had, went to the hospital himelf. His problem wasn’t all that Canadian Club. It was the Pall Malls to which he was also addicted—Taylor had advanced lung cancer. Phillips, who hadn’t seen him since the shooting, had softened enough to visit him in the hospital, where Taylor told him to come back in a week because he had something special in mind for his old partner. But before that week had passed, so had Taylor. Typically, he’d long since written his own epitaph: “When I die, they’ll say, ‘He couldn’t play shit, but he sure made it sound good.’”