The Big Lookback: You Never Can Tell

Thoughts on music for a wedding celebration, from 'The Village Voice,' March 3, 1975

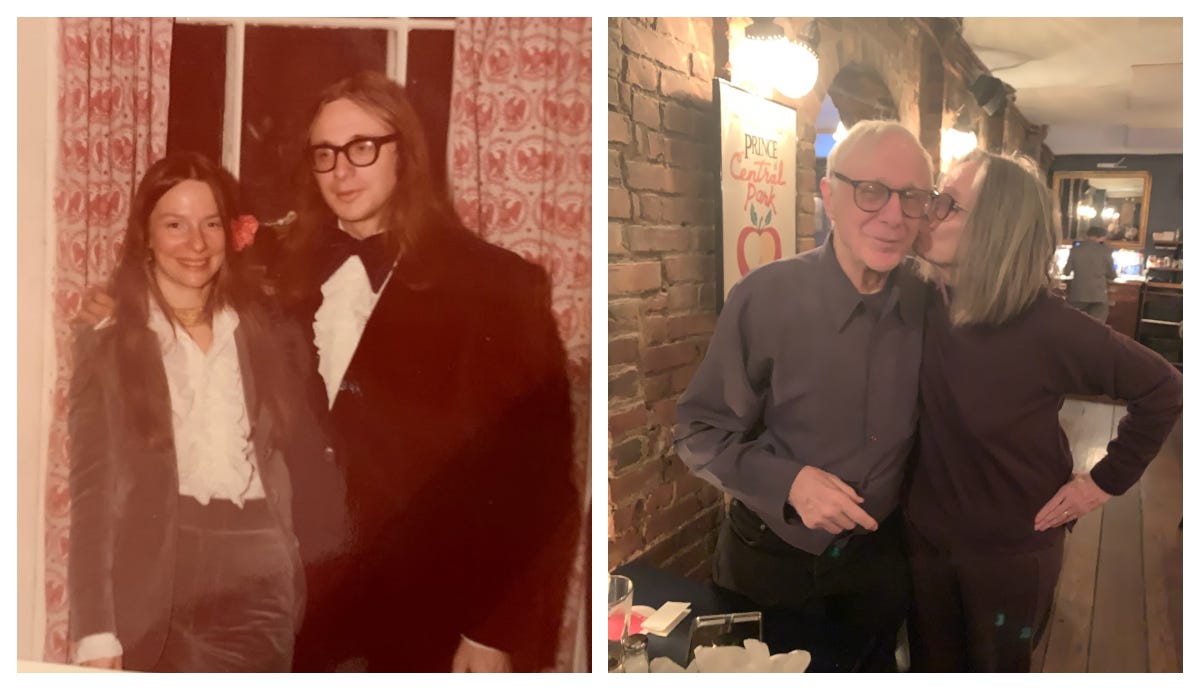

On December 21, I will have been married to the great Carola Dibbell and she to mere me for exactly 50 years. That might not be the legal date, because at the behest of my by now long gone and deeply lamented Dartmouth pal Bruce Ennis, an attorney with the New York Civil Liberties Union before he moved on to the ACLU, we were refused legal matrimony by a New York City Clerk who refused to put his seal of approval on any woman wearing pants like those of the gray velvet suit Carola bought to go with my blue velvet one. So instead we were legally wed by a judge in chambers and then on the 21st in the one that really counted: our rewrite of the traditional vows read by four married couples—two sets of parents, our Dibbell in-laws Joy and Larry Harvey, and my Dartmouth roommate George Szanto and his wife Kit. The site was the brownstone Greenwich Village co-op where Carola grew up, where Larry still resides, and where Joy passed away on August 30 of last year.

The night before the main event, however, we gave a mostly-Voicers party in my painter friend Bob Stanley’s Crosby Street loft. It was several months before I got around to pondering what it was like for us to put together music for that party on what I recall as two reel-to-reel tapes I have so far failed to locate—a disappointment so bitter I didn’t see the point of rerunning the Voice piece that eventuated. That is, until Carola wracked her magic memory briefly and came up some titles: the Rolling Stones’ “Let’s Spend the Night Together,” Dusty Springfield’s “Just a Little Lovin’,” Bonnie Raitt’s “Good Enough,” Dionne Warwick’s “Don’t Make Me Over,” Ella and Louis’s “I’m Puttin’ All My Eggs in One Basket,” Stevie Wonder’s “Contract on Love,” Sly Stone’s “Family Affair,” the Dixie Cups’ “Chapel of Love,” Buddy Holly’s “Peggy Sue Got Married,” John Lennon’s “Oh Yoko,” and Thelonious Monk’s “Tea for Two.”

As regards what I wrote looking back, I should just mention that in 1975 the term “hard rock” signified anything loud and fast with an unmistakable beat—hegemonic metal power-tripping was still down the road. And if Steve West is by any chance reading this, I know I never paid you properly for the photos you took, so by all means send me an address and thanks.

Shortly before Christmas, I had the pleasure of marrying my roommate, partner, and musical advisor, Carola Dibbell, but to tell the truth it wasn’t exactly a rock and roll wedding. The legal ceremony, the one that counts with all the financial overseers who still exploit their power to reward rigmarole, was performed quietly by a judge who asked a couple of pertinent questions and told us we were married when we gave the right answers. The real ceremony , the one that counts with us, was performed by four couples—two pairs of parents, two pairs of long-married friends—who were not, as it happened, into rock and roll. Carola and I did fantasize briefly about substituting Al Green or Barry-Greenwich-Spector for Mendelssohn. In the end, though, we let the service, amended perilously close to deadline from the Book of Common Prayer, provide its own music.

But whenever I do anything significant in my life—especially if it has to do with sex—rock and roll seems to get involved. After all, what’s a wedding feast without music—music for dancing, and music for the wedding feast itself? Since marriage is the culmination of a figurative dance, even a left-footed lead-ass like myself has to relish putting flesh on the metaphor for the big day, and the work of the dance tape went quickly. Because dancing is a practical affair, lyrical considerations soon dissipated, and one tape included Ann Peebles’s “Breaking Up Somebody’s Home” as well as Howard Tate’s “Look at Granny Run Run.” But on the wedding tape, lyrics were a perplexing problem. If not the reactionary weltschmaltz of “Here Comes the Bride” or the smug positive thinking of “We’ve Only Just Begun,” then what? Not a simple question if it’s taken seriously—it took more time to hash out the wedding tape than it took to write the service itself.

Like most contemporary art, rock and roll is not rich in accounts of matrimony that are exemplary or even credible, a failing compounded by its roots in teen. Five years ago I split with the woman I wanted and found writing a music column about it almost unavoidable—breaking up is hard to do, they say but it is a staple of adolescence and hence of AM radio, a part of the natural environment in this unnatural time. In contrast, this music column which is about marrying the woman I want, must have its source in our own efforts. I mean our efforts in compiling the wedding tape, of course, but you’re free to run with the metaphorical resonances.

My column is named after the Chuck Berry song which became the centerpiece of our tape. The song details the post-nuptial bliss of a teenaged Cajun named Pierre and his “lovely mademoiselle.” These children of the ‘50s are notably unliberated; they consume without chic. A “two-room Roebuck sale” completes their apartment the way “TV dinners and ginger ale” fill up their “coolerator.” Their “souped-up jitney” is a “cherry-red ‘53.” And of course they love music: “They had a hi-fi phono, boy did they let it blast/Seven hundred little records, all rockin’ rhythm and jazz/But when the sun went down the rapid tempo of the music fell/C’est la vie, say the old folks, it goes to show you never can tell.”

The English critic-chronicler Nik Cohn thinks “You Never Can Tell” is Chuck Berry’s “most perfect song” because of the way it evokes “the Teendream myth that’s right at the heart of all pop.” Like the cynical popper he is, Cohn gets an added kick from knowing that the song became a hit shortly after Berry finished his time on a Mann Act conviction. But that cuts both ways. Either Berry is a double degenerate for concocting Teendreams after living through a specifically adult Teenmare—the “victim” of Berry’s crime, I should remind you, was 14; she was also, it is said, a prostitute—or else the intensity of his attraction to Teendream is doubly poignant because he can still write such poignant (and funny) songs about it. I get my own kick from “Our Little Rendezvous,” a more explicitly fantastical post-nuptial Teendream that died as a single shortly before Berry was imprisoned. (It is available, like “You Never Can Tell,” on side one of his St. Louis to Liverpool album.) The rendezvous of the title is a spaceship in which the happy couple are to circle the world in perpetuity, listening to rock and roll on their shortwave radio. Was the obviousness of the tongue-in-cheek deliberate, do you think? Did it extend to “You Never Can Tell”? And did all the happy and not-so-happy couples listening to rock and roll on their transistors get the irony?

The answer to that last question is the usual: some did, some didn’t. Much of the rock and roll generation got married as if there were no tomorrow—but not because of rock and roll. It was mostly rock and roll’s conservatives—Pat Boone, say, or the Platters—who, reflecting the ideals and aspirations of a dangerously broad audience and deriving in part from the straight pop schmaltz they contravened to survive, offered variations on a sentiment expressed succinctly by Elvis Presley himself: “For my darling I love you/And I always will.” Although their dense, throbbing harmonies obscured the message, the slow-dance doo-wop groups did the same. In fact, the Five Satins put out one of rock and roll’s first marriage songs, “To the Aisle,” in 1957. But all of those songs were aberrations—for the most part, the always vows of the ‘50s were made as if there were no tomorrow. Marriage was for after high school, like working. That ideal teenager, Buddy Holly, the closest thing to Chuck Berry that the white rock of the time produced and an avatar as surely as Bob Dylan, caught all of its sheer unlikelihood in “Peggy Sue Got Married,” the first half of which equivocates with a wild nervousness, thusly: “Please don’t tell, no no no/Don’t say that I told you so/I just heard a rumor from a friend/I don’t say that it’s true/I’ll just leave that up to you/If you don’t believe I’ll understand.”

Those who don’t think the spirit of Buddy Holly is still abroad in the land, at its most short-sighted as well as its most visionary, should have been around when I mentioned my wedding plans to acquaintances unfamiliar with my firm general views on the subject. Their bemused disbelief was a testament to their liberations from a belief in marriage itself. This sort of liberations—I use the term fully aware of how dog-eared it has become—is simultaneously cynical and utopian: wedlock is rejected, rather harshly, because it sets up a barrier between the individual and life’s endless goodies. Not that apparent paradoxes like this one invalidate the idea of liberation, as some neo-reactionaries hold. Bridging paradoxes is what liberation ought to be about. It is, for instance, an importunate skepticism cut from the same cloth as the impatience my acquaintances feel with marriage that propels the most attractive kind of Teendream adolescent questing. It does begin to look frayed around the edges, however, as it glides toward the near shore of middle age.

Buddy Holly, an admirer of Elvis’s “You’re So Square (Baby I Don’t Care),” obviously sensed this. He rebelled, yes, he really freed himself, but sometimes he was content to just sit there holdin’ hands. Carola and I feel the same way. That’s why we chose to begin the wedding tape with a song that embodies all of the square, acculturated credulousness of pop consumption and little of the calculated conservatism of pop production: the Dixie Cups’ “Chapel of Love.” A number one from the early days of Beatlemania, simple and joyous and foolish; it was spring and bells would ring and we’d never be lonely any more. Just the thing for a December wedding. Followed immediately by a non-hit from around the same time. Artist: a barely pubescent Stevie Wonder. Title: “Contract on Love.” And the hard-headed message, delivered in a high-pitched gurgling shout that would have been unimaginable, especially in a pre-pubescent, before the advent of rock and roll: “You’ve got to si-yi-ying.” Taken together, the two songs seemed to encompass our hopes an apprehensions quite neatly.

Most of the rest of the tape was chronological—20 songs, following a courtship from inception to age 64, capped off by two more that summed up our feelings the way “Chapel of Love” and “Contract on Love” suggested them. The selections were divided almost equally between black and white artists and dominated two-to-one by males in an eclectic range of styles—doo-wop and rock and roll, rockabilly and country, surf music, Beatles and Stones, hard and laid-back rock, vocal and instrumental jazz, torchy and kitschy and campy pop, three or four kinds of soul, even reggae. Now, although my everyday listening habits are also eclectic, I would say that my preference among genres is for hard rock; I listen to more white artists that black and favor male artists (in hard, sad practice) at a ratio of a least eight-to-one. Is it odd, do you think, that on this occasion the habits of a lifetime shifted? Is it amusing? Ominous?

Well, anyone who gets married had better figure on shifting his or her habits—although in the case of cohabitants like myself and Carola, it’s more a matter of celebrating and formalizing and (last but not least) insuring the transformation. Hard rock (repeat: hard) cannot be expected to bend to the needs of this kind of flexibility. To recognize this, though, is not to turn away from the music, but only to put it aside for a period. When the sun goes down the rapid tempo of the music falls. Even at its most teen, black music does relate to a cross-generational community that lives too close to the plight of survival to take domestic arrangements for granted, and although the scant succor that rock and roll has offered female artists is a disgrace, their childhood survival training has prepared them for one area of special expertise within the music—the subtler shadings of the interpersonal.

The one real hard rock song on our tape, “Let’s Spend the Night Together,” softens the general rule that hard rock equates sex with aggression insofar as it deals with sex at all. There are many similar exceptions. But the title does retain an undeniable toughness—a toughness that married folks like Carola and me continue to find bracing and essential—which in turn requires a response. It is no accident that the response we came up with was Carola’s idea: Bonnie Raitt’s “You Got to Know How.” It is also no accident that the answer song is in the same laid-back mode I so often disparage, and that the lyric originated with Sippie Wallace, a female blues singer active 50 years ago: “There’s tricks that I don’t even know/Ones we’ll make up as we go/Whoa mister, when we really know how.”

Thank God for Bonnie Raitt. Our single most difficult task was finding a female autonomy song that didn’t rule out lasting sexual relationships altogether. Our original brainstorm, Lesley Gore’s “You Don’t Own Me,” was much too heavy on the adolescent polyandry for devout monogamists like us, and it was only after much casting about that we rediscovered Dionne Warwick’s “Don’t Make Me Over,” which was adjudged acceptable despite its overall mood of abject dependency. Relatively speaking, the rest was easy, although somehow it was always Carola who argued the women’s songs onto the tape. Three versions of wedding-day fun—one dreamy, one philosophical, one jolly—were followed by Freda Payne's lament over an unconsummated wedding night (there’s safety in humor, I say) which was followed by Dusty Springfield’s evocation of morning sex (Carola’s choice, despite its alarming implication that sex can replace, rather than augment, coffee). After Thelonious Monk attacked the conventional harmonies of “Tea for Two” there were lyrics underlining the function of friends and children and struggle. “When I’m 64,” rather than Randy Newman’s “Love Story,” closed our narrative, although we regret not thinking of “Look at Granny Run Run” until later. The title of Louis Armstrong and Ella Fitzgerald's “I’m Puttin’ All My Eggs in One Basket”—which was composed by Irving Berlin—speaks for itself. But the only way to understand Bette Midler’s wacky, skeptical, cannily acquiescent recasting of “Chapel of Love” is to listen to it in conjunction with the Dixie Cups. That was how we had to go out.

A surface oddity of this compilation is the absence of any of those exemplars of conjugal bliss that the world of rock itself has offered up. Paul & Linda and James & Carly and even harmless Kris & Rita got no nearer to our turntable than the Carpenters. This is partly because we don’t like the music, but as usual it doesn’t stop there. It extends to the people and to the images they have made of their lives together—the McCartneys’ rich-eccentric good times, Taylor-Simon’s therapized good relationship, Kris and Rita’s pastoral good vibes. For each of them, marriage is a repudiation of Teendream. We are adults now, they boast. Isn’t it time you grew up too?

Nope. The one exception amid all this privileged preachifying is John Lennon’s “Oh Yoko,” which if it is not the most jubilant celebration of married love ever recorded is certainly the silliest. I chose to omit it (not even mentioning the title to Carola) because I identify with John off and on, and for a while it has happened to be off. I do not want Bob and Carola to turn into John and Yoko, even if Lennon/Ono are an item again. But I regret this superstitiousness. In silliness there is strength , for all of us. Carola and I may furnish off our apartment with a three-room thrift shop sale and stock our coolerator with home-made seltzer and English muffins, but we have no intention of abandoning the adolescent dreams of personal fulfillment that drove us to the place where we came together, even if we are past 30 and would like to have a couple of kids. The modest hedonistic materialism of Pierre and his madame evolves naturally (although with difficulty) into complex systems of love and community like the one suggested by Sly Stone in “Family Affair,” a song he wrote long before making a pig of himself at his own wedding.

Shortly before he died, Buddy Holly got himself a place in the Village. He wed a Puerto Rican girl—Peggy Sue had gotten married too, to somebody in his old Texas band—and I imagine him there, holdin’ hands and playing blues and listening to hard rock and thinking. Don’t let anybody tell you different. Buddy Holly lives.

Thought I'd note that Carola's magic memory got something wrong, which does very occasionally happen. For reasons I obviously no longer recall, we seem to have vetoed "Oh Yoko." Thanks to all well wishers and my hopes and belief that you can be as fortunate in your love life as I've been. in mine. It can be done! And you don't even have to hitch up with (or be!) the best-looking 79-year-old in your neighborhood. In fact, that's by no means the important part.

Mazel tov, you crazy kids! May blessings continue to find you.