The Big Lookback: The Yankees Learn to Lose

As a topsy-turvy, streaky season draws to a close (or does it?) some thoughts on this year's Yankees and the Yankees of 47 years ago

Before there was such a thing as rock criticism, my dreams of popular culture journalism focused on sportswriting. Boxing was the favored athletic endeavor of the thinking litterateur once Hemingway exhausted bullfighting, and in the end it was A.J. Leibling’s The Sweet Science that nailed my conversion to journalism. But baseball had been my great love since well before I infuriated Mr. Brenner by declaring “The Rhyme of the Ancient Mariner” inferior to “Casey at the Bat” in ninth grade, and from Bernard Malamud’s The Natural to Jimmy Breslin’s Can’t Anybody Here Play This Game? I was immersing in baseball lit well pre-Liebling. My first published baseball piece was a 1971 review of Jim Bouton’s Ball Four for Fusion. But once ensconced at The Village Voice I leveraged my connections into half a dozen or so meaty, mostly reported essays on baseball and actually got to cover the 2000 Subway Series. So as this Yankee season draws to a close—or does it???—I thought the 1974 kickoff of my Voice baseball coverage would make a good Big Lookback.

I’ve been a Yankee fan since 1949, when I was seven. Slacked off in the ‘80s before I was brought back on board by now 82-year-old Yankee radio man John Sterling and his partner Suzyn Waldman, a rare woman sportscaster. Sometimes I watch on TV, but so as not to impose on Carola more often follow with an earphone on my pocket radio or, when I’m writing, via mlb.com’s Gameday feature, which reports each pitch a few maddening seconds after it is thrown. If the game’s a good one, however, Carola and I often watch the final inning or two together. So in this topsy-turvy year I can report that we’ve both not once but twice witnessed the maddening closer Aroldis Chapman load the bases with nobody out only to luck into a grounder to my favorite Yankee, sure-handed Gio Urshela, who then started a 5-4-3 triple play—three seconds, high anxiety to game over, and note that triple plays are rare and usually involve everybody running on a line drive. We also watched Gerrit Cole finish off a 129-pitch shutout and saw the last five innings of Corey Kluber’s no-hitter because I’d noticed how the game was going on Gameday.

But this has been a such streaky season—many injuries, many Covid sick weeks, many batting slumps, many losing streaks, a game Chapman lost on a grand slam. The worst of countless disappointments came one Sunday when I needed to get to the gym. So first I checked Gameday and saw that Domingo German was pitching a no-hitter with a 3-1 lead in the seventh with Yanks loading the bases. Looked pretty good, right? Only when I got back I checked the score and my team had lost 5-4 as the normally untouchable Jonathan Loaisiga imploded. I went off baseball for a week after that. I should mention too that both Kluber and German developed sore arms after their big games. Pitchers no longer train for long outings.

All of which is a long preamble to indicate why this Big Lookback is going up Tuesday rather than Wednesday as usual, which is to finesse a Tuesday night game certain to drastically inflect the Yanks’ ongoing 2021 storyline: Yanks at Fenway, winner makes the playoffs, loser goes home. In the best outcome, the game would be at Yankee Stadium. But given Sunday’s game against the Tampa Bay Rays, which I watched every minute of while Carola’s women’s group Zoomed in the dining room, I’ll take what we got, because this was the tensest game I can recall—ever. Crippled by sportswriting’s presumption of neutrality plus the reduction in tension a known outcome provides, nothing I’ve read about it conveys that. Tampa Bay has been the best team in the league all season and had just creamed the Yanks 12-2 Saturday after squeaking out a much less inevitable 4-3 win Friday. With the postseason just around the bend for both teams, neither relied on an ace, yet the scoreless innings rolled on. As they did it seemed ever more possible that one of the Rays’ many home run threats, particularly trading deadline Hall of Fame pickup Nelson Cruz although note the 33 smacked by .216-batting catcher Mike Zunino and there are others, would loft one to right. But it was still 0-0 after eight.

This may seem paranoid given that the Rays only got five hits including two doubles off an overachieving succession of Yankee pitchers, with sharp even though recently injured starter Jameson Taillon, inconsistent changeup specialist Wandy Peralta, and home run-prone Chad Green especially scary. Also scary was the play of the game, in which the sure-handed, all-out Urshela snagged a popup on the run and dove down the stairs of the Rays’ dugout, where he held on to the ball without breaking any bones—not only did he walk away on his own after five minutes, he stayed in the game. But five hits is a lot when in the first eight innings your guys only get one. Happily, the recently injured Loaisiga proved the team’s sharpest reliever once again, Chapman only gave up a walk, and in the bottom of the ninth Rougned Odor smacked hit number two, base-stealing whiz Tyler Wade took his place, a flyout and a second hit left Yanks on second and third, and Aaron Judge came up.

The six-nine Judge is on his way to being Mr. Yankee if he isn’t already—fleet and powerful, affable and modest, a very good guy. He hits a lot of home runs and strikes out too much. But this situation did not require a home run. So as if he knew exactly where the ball would go, he smacked a hard ground ball off the pitcher toward second and Wade raced home, beating the throw by plenty. Nobody knows what will happen tonight. But the chance that it’ll be that excruciating and exhilarating is minuscule.

Village Voice, Oct. 10, 1974: The Giants were a fallen empire—declining rather than defeated, more like Great Britain after World War II than Spain after the Armada, except that they had become so ordinary that they no longer warranted grandiose comparisons. A commitment to the Giants was an honorable thing, like a commitment to everyday life, its disappointments and boredoms and occasional triumphs all suffused with the half-pleasant, half-painful sense that there had once been something much better.

To root for Brooklyn, on the other hand, was to participate in a tradition of thwarted hope that had been mostly fictional all through the ‘40s, and had thus come to center on one overextended metaphor—the defeat of the Dodgers by the Yankees in the World Series. The masochism of the Dodger fan bordered on spiritual self-importance. This sort of shrill loyalty to the underdog is essential—it makes Jackie Robinson possible. But its cultural narrowness was exemplified by the Dodgers’ status (made semi-official by the letters of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg) as the baseball arm or the C.P.U.S.A.

Which brings us to the Yankees, who were winners—not like Yankee Doodle, but like Yankee go home. By the ‘50s, Ruthian brawl and DiMaggio’s spreggiatura had given way to Mantle’s gum-chewing and beaver-shooting, and the team’s color came from its manager, an eccentric banker. The usual white Southerners were flanked by the usual immigrants, and there was even an American Indian, but the immigrants were often third-generation rather than second-, and the team was scandalously neglectful about investing in black players. All of which could be brushed aside by a young fan who happened to love the Yankees even more than he loved Willie Mays. Brought up by his Giant-fan father to value individuality, the young fan might identify with Phil Rizzuto, who was short. Or he might delight in old Johnny Mize with a swing like Ted Williams (almost) and so much gut he couldn’t get down for a hard grounder. Eventually, he might even ponder the mystery of Mantle, a boyish oaf who played the last half of his career in almost continual pain, his face impassive or grinning blankly except when one of his knees actually gave, and wonder what such self-control said about the supposed obtuseness of American power. But that wouldn’t be why he loved the Yankees. He wouldn’t even have a choice. He would love the Yankees because they always won.

And that was why most baseball fans hated them. To the rest of America, they of course embodied the unaccountable power of New York, but in New York they represented more than the then-powerful American league. Especially among Jews and blacks, hyperaware of factors like blondness (Mantle and Maris and Kubek) and Wasp names (Mantle and Woodling and Turley and Boyer and Richardson), they came to symbolize the triumphant arrogance of America itself. The Yankee-hater fantasy of that arrogance brought down grew so full and rich that it was eventually converted into a Broadway show.

The year the Yankees lost the pennant was 1954; I am not the only young fan who learned about death when his team lost the Labor Day doubleheader that was scheduled to inspire their miraculous recovery. Yet hate-filled fantasies to the contrary, total conquest is not the American dream, and when the Yanks came back to win for (yes) four more years, it was sufficient. This American dream wasn’t about happiness without human cost—we knew that the Athletics and the Indians and the Senators were failures, even if we weren’t anxious to empathize. And It wasn’t about happiness without struggle—our team hurt and fought and doubted and sometimes lost not only the battle but the war. No, it was even more dangerous than those. It was about happiness without surcease—the rainbow at the end of the rainbow, the ever-after that rolled on when the movie stopped.

For those lucky enough to care about them—a category that included, forget the Dodger propaganda, not only Park Avenue potentates and racist lumpen but good old-fashioned upwardly mobiles like me and maybe you—this dream was a healthy antidote to the infectious obsession with tragedy that seems to go with growing up in New York. It ended when the Yankees fired a colorful second-generation immigrant manager, Yogi Berra, who was nervy enough to win a pennant that Ralph (“The Major”) Houk—Berra’s boss and predecessor as well as his third string from playing days—believed he had lost. Berra’s replacement was a Middle Western world champion named Johnny Keane who was dead two years later, by which time the Major was the manager once again. For the next decade, as the Yankees were bought and sold by CBS, the team struggled madly to develop/buy a pennant winner. Until this year, they never had even a contender past Labor Day.

Perhaps it is not so strange that it was only after the Yankees’ ruin that this Yankee fan began to apprehend what might be called the nuances of compassion. The process was more subtle than learning to regret the human cost of happiness without surcease and being forced to suffer its struggle, although both were part of it. Ultimately it means coming to terms with the limitations of the game—not dumping the metaphor altogether, for to reject its playfulness would be cynical and to reject its finality sentimental, but to qualify the equation of winning and happiness. This is only one way of explaining it; admittedly the Yankees loom small in an experience that also included the Beatles, Vietnam, one birthday per year, and a relationship with a female Giant fan. But for the loyal fan—and many proved faint-hearted while others grew swinish—who followed the doomed hopefuls (Rich Beck! Roger Repoz! Ron Woods!) and useless downhill star-men (Rich McKinney/Felipe Alou/even Ron Swoboda) to the end of each season, which usually occurred in July, the team’s disastrous mediocrity was a lesson in humility.

In 1974, the Yankees tried something different. First Houk left, a move cheered by all sane loyalists. Then they tried to buy Dick Williams, according to legend the best manager in baseball. Fortunately stymied by Williams’s owner, they resorted to Bill Virdon, a freshman manager dismissed by Pittsburgh so arbitrarily that it’s possible the Yanks were doing penance for Yogi. They then proceeded to stock the club with the most motley collection of rejects and weirdos this side of the ‘62 Mets.

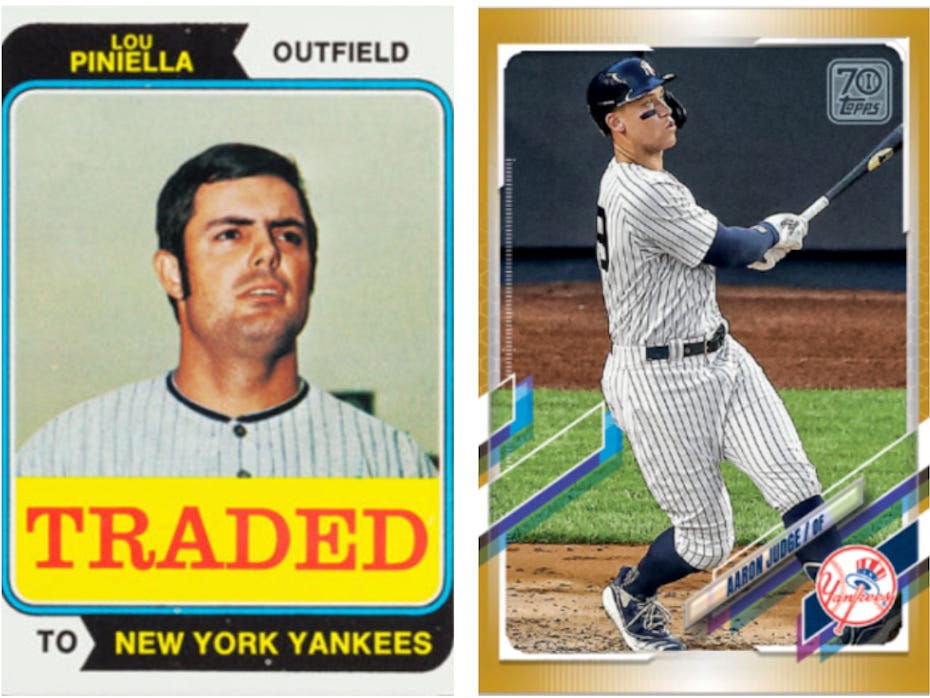

These were not the big names and stellar prospects of our season in limbo. They were certified failures. Pat Dobson and Sam McDowell, former 20-game winners purchased for big cash and high ERA. Lou Piniella, a good-hit no-field lunk who has been observed lolling against the outfield fence during pitching changes. Bill Sudakis, who could run when he had knees. Elliott Maddox, who had hit .252 with two home runs in his big year. Walt Williams, a/k/a No-Neck, who began the season needing not only a periscope but contact lenses. Even after the season began the second-raters kept coming. Half our pitching staff was traded away for a neurotic first baseman and two pitchers whose 1973 ERA added up to 9.35. We went to the worst team in the league, soon to be managed by Dick Williams, for two discards: Rudy May, who had led the league in balks last year, and Sandy Alomar, a second-baseman who was the victim of the same kind of anti-mediocrity campaign that sent our own Horace Clarke to San Diego. We purchased Larry Gura from the minors, where he had lost as many games as he’d won; in the majors, his won-lost over four years was 3-7.

Like Met fans, but without their occasional predilection for low camp, real Yankee fans—the ones who continued to swell the club’s dwindling attendance—are blessed with optimism. With our heritage of happiness, we automatically assumed that these ragtags might be champions. By July we were last. Our best home run hitter had yet to power one out of Shea Stadium, where we were playing while The House That Ruth Built was redecorated. Our second-best home run hitter set an April record with 11, then settled down to one a month. Our best pitcher, the sole survivor from 1964, was disabled for the rest of the season. Our All-Star catcher couldn’t throw overhand. We had lost 20 of our last 21 in the home park of the league leaders. And yet the best of us knew that the season wasn’t over.

As you may have gathered from reading the back page of the News in the subway, it wasn’t. The Yankees almost went all the way, and if the Yankee-haters don’t prevail, Bill Virdon (“I don't lie because I hate having to remember what I said”) will be manager of the year. He moved the petulant Bobby Murcer to right, where he belonged, and came up with a fleet black center-fielder who hit .300, Elliott Maddox. He gave Lou Piniella and Pat Dobson and Jim Mason the chance each deserved, and got top form or better from Rudy May and Sandy Alomar and Larry Gura. (He also held on to Walt Williams, who hit .113. Wait till next year.)

The Yankee ragtags were an exceptionally resilient team—in a pattern I noticed, they would often lose the first game of a series and then take the next two. By the time they swept aside the Fenway jinx in September, a miracle I was privileged to witness in person, they looked like winners. But the Baltimore Orioles, now the oldest American League dynasty, took the Yankees three straight in their final series, just like the Yankees used to. The momentum, not to mention the lead, was theirs. The Yankees didn’t choke, winning eight of their next 10 games. Unfortunately, neither did the Orioles.

One of the pleasures of the ‘74 Yankees was their polyglot, multiracial flakiness, right down to their Jew (the somewhat schmucky Ron Blomberg) and their blaek-who-was-studying-Judaism (the inspired Elliott Maddox). They fought, threatened to quit, razzed each other hard. The final Sunday of the regular season, after their seventh straight win over Cleveland had been cancelled by yet another Baltimore comeback, they got drunk on the way to Milwaukee. Bill Sudakis and Rick Dempsey, important early-season stopgaps who no longer saw action, got into a brawl, and Bobby Murcer tried to stop it. Baltimore won again Monday and Tuesday, making the Yanks’ Tuesday night game a mathematical necessity. Murcer couldn’t play.

He had injured his arm sliding, yes, and he had reinjured it in the fight. The bat loss was minor; Alec Johnson, another weirdo picked up late in the season, was an adequate replacement. But although Murcer had been a shitty center-fielder, his speed and glove and arm were ideal in right, where the lead-footed Piniella would have to replace him. The Yanks scored twice in the seventh with Johnson batting in a run. And in the Milwaukee eighth, it happened.

Routine fly to deep right. Maddox and Piniella move toward the ball; Piniella, who has long since belied that no-field bullshit, calls for it and then, inexplicably, shies away. A pure lapse, pressure drop, a triple. The next batter sends a sinking liner to center. Maddox, whose shallow center has been a delight all season, tried to shoestring it. Another lapse. One run will tag up even if Maddox succeeds, while if the ball goes through . . . It goes through, another triple, and the season. Had Maddox safetied the ball for a single, the Yanks would have escaped with the inning and the ballgame. Piniella’s error was more horrible, but it is the image of Maddox, my favorite of favorites, that stays in my mind. Not the ball spurting or Frank Messer grimly analyzing. Just Maddox, diving foolishly, over and over again.

This is a new thing for the Yankees. We always won the close ones, always; when we lost, we lost big, like for nine years. It all feels very Dodgerish. I can even say wait till next year, but I can’t be certain. So many unknowns playing over their heads, or were they? It could be failure, or happiness without surcease—if that’s what I want to dream about.

And yet when I get Maddox out of my head I feel very happy about baseball. It’s one of the few things that makes me feel happy these days. And one nice thing about my Yankee youth is that I like to be happy. The team was my entree to that American dream, a dream denied to a lot of New Yorkers, and it’s nice to think that this flaky New York team can partake of that myth. Meanwhile, the Dodgers won in their division, and I’m rooting for them to go all the way.