The Big Lookback: The Three Roches Crack Wise

From the Feb. 20, 1978, "Village Voice": Carola Dibbell on the Roches live at Kenny's Castaways

A month ago Rock & Roll Globe published this extraordinary interview with Terre and Suzzy Roche by veteran rock scribe and longtime Pazz & Jop stalwart Jim Sullivan. I hadn’t thought about the Roches in a while, in part because I didn’t own their debut and still-finest album on CD, an oversight I have now corrected. But before I even did so there was another oversight I felt compelled to correct: going public with one of the many examples of her Village Voice rock criticism my wife and musical advisor Carola Dibbell hadn’t put up at her site. Fortunately, she did have a fragile 42-year-old clip, so I did half an hour of data entry and sent it to Tom Hull, who posted it posthaste.

One reason I did this is that—cf. the Cornershop piece I linked to in my Josh Clover review—Carola never wrote a dull Riff and I want every one to be available. (Many are still uninput. Two I regularly reread for the laughs alone: “Irish Catholic” and “Big Mac.”) To my knowledge, “Three Roches Crack Wise” was the sisters’ first review in any major outlet. The anonymous female pal it quotes is Ellin Hirst a/k/a Ms. Clawdy, a star of Ellen Willis’s renowned “Beginning to See the Light” summum. Carola’s Roches review is absolutely worth reading—lotsa laughs. But the reason I felt compelled to cite it isn’t just my uxoriousness—it’s that it set off a chain of events that Sullivan’s interview overlooks. The piece’s biggest admirer was Voice senior editor Karen Durbin, who in ‘90s was the paper’s editor-in-chief for a while. A major music fan—she did some terrific Rolling Stones coverage for us—Durbin went to see the Roches first chance and was so smitten she wrote a major Roches feature that put them on the map the way Carola’s brief review couldn’t. A few weeks ago I contacted the Voice to see if we could dig that out and link to it, but the paper’s archives are a mess these days, and Durbin isn’t available for comment either. But the Voice played a role germinating the Roches debut and sui generis masterpiece and I’m here to brag about it.

Of the many odd things about what us old CBGBites think of as the punk period, the oddest being that it was also the disco period, the second oddest is the rise of not one but two long-running folkie sister acts having no apparent structural relationship to punk, disco, or “rock”: the Roches and also if not more so Kate & Anna McGarrigle. Like disco in an altogether different dimension, the two constituted a blow against rock sexism as sharp as if less powerful than Patti Smith’s. But forced to choose, as fortunately I’m not, I’d take the McGarrigles, who announced themselves with not one but two remarkable albums, one of which included the title song of Linda Ronstadt's breakthrough 1974 Heart Like a Wheel. I’ve been playing the rest of the Roches’ catalogue in the wake of Sullivan’s piece, and while it holds up pretty much as well as I thought at the time, debut excepted I don’t find that even the best of it has quite the heft of several late McGarrigles albums I could name, and the 2003 Warner best-of jocosely titled The Collected Works of the Roches is now a rarity. Nevertheless, they remained both idea people and clowns just as Carola hoped—and as she also hoped, earned a living at it. If you call that living—which to their credit they did and still do.

There is a kind of woman who experiences uncontrollable urges to wear boxer-style underpants, or to get drunk and insult the useful, or to buy shoes out of pity for them, or to make terrible crucial decisions from pure curiosity. A while ago, two such women went to see the Roches, the idiosyncratic sister trio who headlined at Kenny’s Castaways last week, and before the first number was half through, the skeptical one had turned red every place that showed and whispered, “They’re the best!” to the other one. The other one was me, and I already knew. Not that this wry group—specializing in acid judgments, sweet contrapuntal harmonies, intricate word and rhyme play, and outright buffoonery—is the new Beatles, but that, if anyone is us up on that jukebox, sister, it’s them. I don’t just mean us thinking clowns, either. I mean anyone who believes in postponing compromise for as long as possible. My guess is that the Roches have hit on humor as the best way to tell an audience complex truths engagingly while while staying true to their own relatively modest and relatively thorny selves.

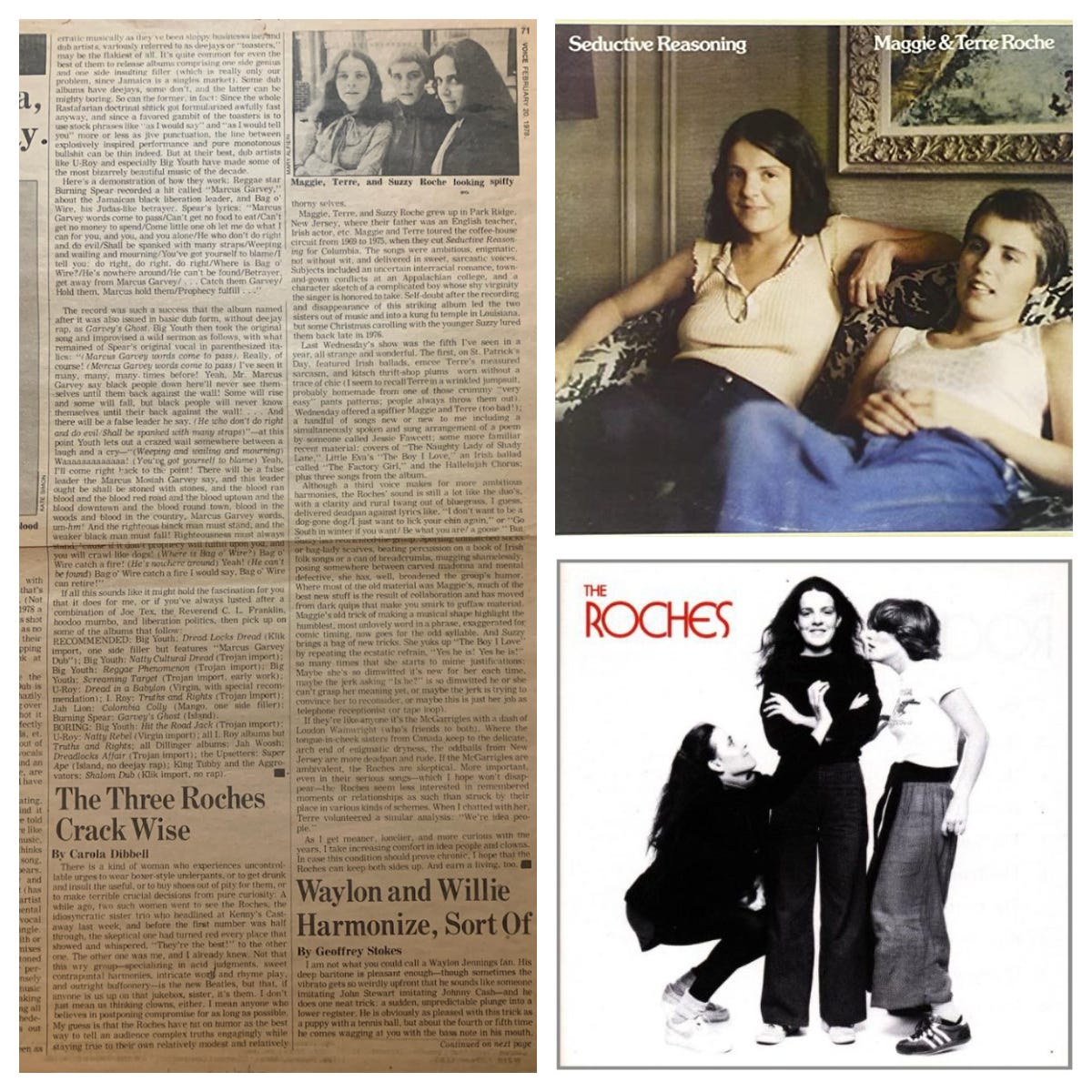

Maggie, Terre, and Suzzy Roche grew up in Park Ridge, New Jersey, where their father was an English teacher, Irish actor, etc. Maggie and Terry toured the coffeehouse circuit from 1969 to 1975, when they cut Seductive Reasoning for Columbia. The songs were ambitious, enigmatic, not without wit, and delivered in sweet, sarcastic voices. Subjects included an uncertain interracial romance, town-and-gown conflicts at an Appalachian college, and a character sketch of a complicated boy whose shy virginity the singer is honored to take. Self-doubt after the recording and disappearance of this striking album led the two sisters out of music and into a kung fu temple in Louisiana, but some Christmas carolling with the younger Suzzy lured them back in 1976.

Last Wednesday’s show was the fifth I’ve seen in a year, all strange and wonderful. The first, on St. Patrick’s Day, featured Irish ballads, MC Terre’s measured sarcasm, and kitsch thrift-shop plums worn without a trace of chic (I seem to recall Terre in a wrinkled jumpsuit, probably homemade from one of those crummy “very easy” pants patterns; people always throw them out). Wednesday offered a spiffier Maggie and Terre (too bad!); a handful of songs new or new to me including a simultaneously spoken and sung arrangement of a poem of someone called Jessie Fauset; some more familiar recent material; covers of “The Naughty Lady of Shady Lane,” the Crystals’ “He’s Sure the Boy I Love,” an Irish ballad called “The Factory Girl,” and the “Hallelujah” chorus; plus three songs from the album.

Although a third voice makes for more ambitious harmonies, the Roches’ sound is still a lot like the duo’s, with a clarity and rural twang out of bluegrass, I guess, delivered deadpan against lyrics like “I don’t want to be a doggone dog/I just want to lick your chin again,” or “Go south in winter if you want/Be what you are/A goose.” But Suzzy has reoriented the group. Sporting unmatched socks or bag-lady scarves, beating percussion on a book of Irish folksongs or a can of breadcrumbs, mugging shamelessly, posing somewhere between carved madonna and mental defective, she has, well, broadened the group’s humor. Where most of the group’s old material was Maggie’s old trick of making a musical shape highlight the humblest, most unlovely word in a phrase, exaggerated for comic timing, now goes for the odd syllable. And Suzzy brings a bag of new tricks. She yuks up “The Boy I Love” by repeating the ecstatic refrain “Yes he is!” “Yes he is!” so many times that she starts to mime justifications: maybe she’s so dimwitted it’s new for her each time, maybe the jerk asking “Is he?” is so dimwitted he or she can’t grasp her meaning yet, or maybe the jerk is trying to convince her to reconsider, or maybe this is just her job as telephone receptionist (or tape loop).

If they’re like anyone it’s the McGarrigles with a dash of Loudon Wainwright (who’s friends to both). Where the tongue-in-cheek sisters from Canada keep to the delicate, arch end of enigmatic dryness, the oddballs from New Jersey are more deadpan and rude. If the McGarrigles are ambivalent, the Roches are skeptical. More important, even in their serious songs—which I hope won’t disapper—the Roches seem less interested in remembered moments or relationships as such than struck by their place in various kinds of schemes. When I chatted with her, Terre volunteered a similar analysis: “We’re idea people.”

As I get meaner, lonelier, and more curious with the years, I take increasing comfort in idea people and clowns. In case this condition should prove chronic, I hope the Roches can keep both sides up. And earn a living, too.