The Big Lookback: The Old 97's

“You May Think It’s Stupid, Rhett Miller thinks It’s Art,” The Village Voice, Mar. 27, 2001

I was so pleasantly surprised by the Old 97’s’ American Primitive, the first album of theirs I’d even noticed since 2017’s less impressive Graveyard Whistling, that I was reminded that way back in 2001 I’d written a meaty Voice column about this now long-running band that I set about unearthing it from my 2017 Duke anthology Is It Still Good to Ya?. There I soon learned that unlike the Perceptionists, Gogol Bordello, Mary J. Blige, and Lori McKenna, the Old 97’s hadn’t made the cut—and also that although those are all pieces I’m also proud of, I thought “You May Think It’s Stupid, Rhett Miller thinks It’s Art” was even better and, at this point in time of more historical moment. It’s a remnant of a time when many “alt-rock” bands had consciously “literary” values and ambitions, and while there certainly still are such bands, this now seems like a dated, all too “straight” conceptualization, which in most cases I have no doubt is. But I was impressed then and remain impressed now that in the course of an hour-long profile interview with a bandleading singer-songwriter almost 30 years my junior, I could be schooled about the virtues of a prestigious fictioneer and poet, by then dead of lung cancer for over a decade, who I’d always regarded as overly doleful, New Yorkerish, and middlebrow. Admittedly, to an extent I still do. But re-encountering this piece makes me think that maybe I should check him out once more and see how he’s aged. So I thought I’d post it here.

In June of 1999, the Old 97’s flogged the impossibly catchy Fight Songs by opening for Cake at a half-filled Roseland. Although I thought they needed a snazzier guitarist—“a Junior Brown protege who knows something about Robert Quine,” to be precise—I recognized every song, enjoyed Rhett Miller’s practiced awkwardness, and couldn’t stave off that now-or-never feeling. Sometimes a band makes a record so good that they can’t endure the aftermath—they deserve to be kings of all the world, and here they are opening for Cake. So when Miller’s publicist brought him by, I gently asked what he planned to do for an encore. That obviously wasn’t a question he was expecting, but he didn’t seem worried about it, and I feared for his innocence. Fight Songs finished 34th Pazz & Jop and SoundScanned out at around 75,000, doubling the sales of the 1997 Elektra debut Too Far to Care. Then the band sank from normal view. Last November I noticed that Miller was performing solo at the Fez and assumed the Old 97’s were history. A fairly arty guy, he’d never seemed content in Dallas anyway. These things happen.

Only they haven’t happened to the Old 97’s. Incredibly in a time when the conglomerate idea of artist development is strong-arming likely-looking indie labels into distribution deals, Elektra went ahead and underwrote an eight-year-old guitar band's fifth album. From regional debut to songful Bloodshot feint to faux-alt-country Elektra move to the terrific pop-rock Fight Songs to—what, them worry?—the equally yet dissimilarly terrific pop-rock follow-up Satellite Rides, I’d compare the Old 97’s to the Replacements circa Tim. The Old 97’s are the lesser band. But note that where Tim began Paul Westerberg’s pathetic progress from bandleader to genius-with-backup, Satellite Rides is just the opposite. Play Fight Songs up against it and you realize that, sonically and dramatically, the earlier album is dominated by a singer-songwriter—Miller’s career goes back to his middle teens, when he was a Deep Ellum folk prodigy. Miller’s talk about cutting the last one on the fly from L.A. and moving back home this time isn’t just the nice-nice of a frontman who decided going solo was a bad career move. The songs, craftily shaped though they remain, feel more dynamic, organic, all that band stuff.

Such distinctions matter not a whit in the macroprofit world where the three finest Old 97’s albums were capitalized, with Satellite Rides returning to Too Far to Care producer Wally Gagel (other big credit: Sebadoh) from Fight Songs’s Andrew Williams (other big credit: Peter Case). With very few exceptions—Wilco, the Flaming Lips, maybe one or two more, all of whom long since broke 100,000 sales—the majors no longer consider the Replacements a viable business model. Which given what happened to Paul Westerberg is perhaps understandable, and also perhaps for the best—a way of weeding out greedheads and wankers, guaranteeing the economic realism and musical commitment of rock and rollers who make their records for independent entrepreneurs and their money on the road. If you fancy extra options in your rock subculture, however, then suddenly this little band you've barely thought about becomes rather significant. Just let them double their sales again, an Elektra marketer told me, and they’ll almost certainly stay on longer.

So I’m pleased to report that the Bowery Ballroom was jumping at the Old 97’s’ jam-packed March 1 gig. Out of normal view they’d sprouted a cult, so that when Miller kept coyly silent after the guitar break on his one-night-stand classic “Barrier Reef,” the house yelled “My heart wasn’t in it/Not for a single minute” for him. Bands get the audiences they deserve, and these excitable nerds who came out for the Old 97’s and knew all the words to their songs seemed sweeter than the fans who shout Ben Folds’s lyrics. Certainly sweet is how Miller plays it. Quite handsome in a stringbean kind of way, he favors the same chinos, short-sleeved shirts, and canvas tennies as the rest of the band, but he always stands out. In 1999 he featured a splay-legged jump that’s given way to a mock-yet-not star-time move he calls “my half Townshend”—a loose-wristed, rotate-from-the-elbow strum that had the longtime admirer behind me crying out. Miller’s old bass-playing partner Murray Hammond harmonizes modestly and sings lead on his own songs, and right behind them is drum dynamo Philip Peeples, with guitarist Ken Bethea listing off to the side with a discretion I soon came to appreciate. Miller isn’t Paul Westerberg, or Matthew Sweet either—not only doesn’t he need a snazzier guitarist, musicianship too quicksilver or corroded would ruin the effect he’s going for. Alt-country was a natural side trip because he aspires to simplicity. Evoking the Beatles or even the Crickets, Buffalo Springfield or even Lynyrd Skynyrd, the Old 97’s are prepunk the way nearly every other halfway decent pop band of our era are postpunk. Yet there’s no history lesson about them. This is just what they do.

All alt-rockers are aesthetes, but for the most part they’re pretty woozy about it, mixing and matching in the assumption that everything will cohere by force of their woefully indistinct personalities. The Old 97’s are sheer clarity and discipline by comparison, as formalist as the Ramones. Yet somehow they’re never severe. Their fundamental principle is laid bare in the fed-up refrain “What’s so great about the Barrier Reef/What’s so fine about art?”—or, even better, a couplet from the Bloodshot-period “Victoria”: “This is the story of Victoria’s heart/You may think it’s stupid but I still think it’s art.” And by sticking stupidly to heart and letting the art take care of itself, by ignoring process and attending to content, their last two records justify Miller’s latest credo: “I believe in love but it don’t believe in me.”

There in eight of the commonest words in the language is the metatheme of prepunk pop-rock, where unhappy love songs outnumber happy ones and everything else is a novelty. Yet though the credo’s from “Rollerskate Skinny,” a Satellite Rides winner about an elusive Hollywood cutie Miller hopes to save from a bad end, examination of the two albums reveals another difference. On Fight Songs, the love songs are marked by distance if not dissolution, and the cheerful exception is named after the street where she lives, which is named after the inventor of the atom bomb. Satellite Rides is somewhat more optimistic. “King of All the World” (as in “You make me feel like I’m the”) isn’t the opener and lead single just because openers and lead singles are supposed to get the blood flowing. All right, maybe it is. But the Old 97’s are formalists. So it’s thematic as well.

Miller acts like a kid and is youthful enough to put the act across—in a less buff era you could imagine him milking his looks for girl appeal, and he might yet. But in fact he’s 30, the age when male rock and rollers’ star-crossed love lives start seeming more callow than cute. So although he may sincerely believe that love doesn’t believe in him, like many songwriters before him, he’s right on time to be perking up a little. It’s true that his prospects never get sunnier than on the opener, and that he probably considers it just as thematic to end with the hyperactive “Book of Poems” (as in “I got a real bad feeling that a book of poems ain’t enough”) and the doleful “Nervous Guy” (as in “goodbye goodbye from a”). Still, I’m impressed by Satellite Rides’ game come-ons. The rakish ones connect first—the thwarted bowling metaphor of “Rollerskate Skinny,” “Buick City Complex” defying the wrecking ball with public phone sex, and “Designs on You,” as sly a proposal of premarital adultery as Prince’s “Head” is bold. It takes longer to notice the two-minute acoustic “Question,” buried in the album’s middle. It’s nothing, really—just a sketched encounter in which a bashful she has a good cry and takes the long way home with the he who brought it on. Yet it has one matchless virtue. It feels like a viable romantic model.

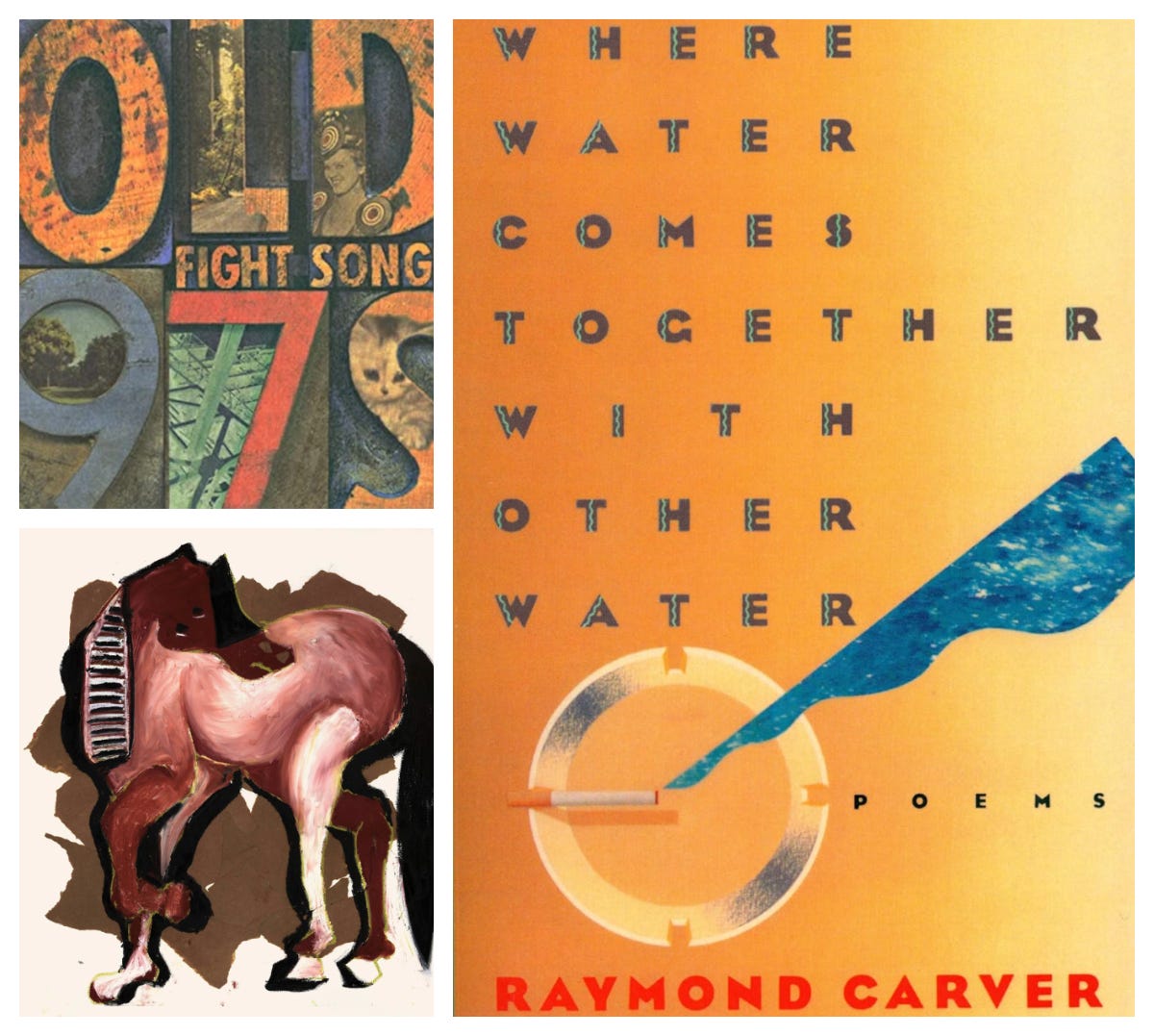

Then again, the thing about rock and roll of the unironic sort the Old 97’s make their lifework, especially once the band stuff is taken care of, is that at some deep somatic level even its unhappy love songs are pretty viable. There’s a future unknown to literature in the marrow of its rhythms and the throb of its voice. That’s an axiom of the Old 97’s’ formalism. It’s why Fight Songs and Satellite Rides are of a piece for all their distinctness, why Miller believes he can say what he has to say in a song of 100 words. Maybe too it’s why he tells interviewers his favorite writer is the American miniaturist Raymond Carver, why in homage to the famed Carver collection What We Talk About When We Talk About Love, which I’d found pinched and complacent about it, there’s a grim track on Fight Songs called “What We Talk About.” Backstage at the Bowery I tried to get Miller to back down on this judgment. He responded that people were wrong about Carver, missing the “human sentiment” in him, and recommended a book called Where Water Comes Together With Other Water. Turned out to be poetry, not fiction; turned out to be fairly great; turned out to be from Carver’s controversial “second life,” after he’d stopped drinking and gotten less grim, although he still spent much time pondering death and loss, as who doesn’t? I conluded that Miller wasn’t as innocent as I’d feared.

In romance, after all, a book of poems rarely is enough. In art sometimes it can be.