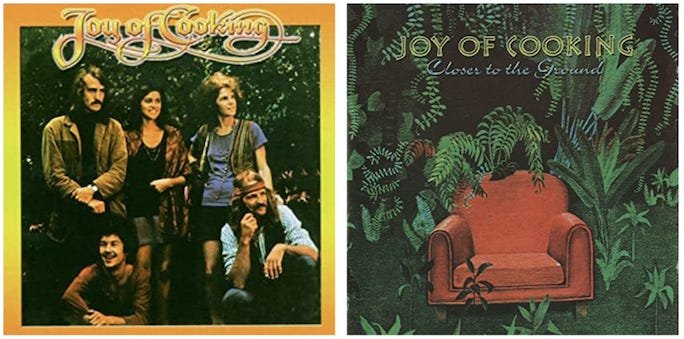

The Big Lookback: Joy of Cooking

The 50th anniversary of Joy of Cooking’s first-of-its-kind first album

I was eyeballing this April, 1971, Village Voice piece—which is collected in my now out-of-print 1973 Any Old Way You Choose It comp and on my website like almost all my writing—as a 50th anniversary special to launch And It Don’t Stop’s monthly Big Lookback feature. But then Peter Stampfel finally delivered his crowning achievement and it had to wait. So here a month late is a reminder that Joy of Cooking’s first-of-its-kind album once existed and the news that it still sounds fine, as I’ve determined by streaming it four or five times in the past month.

White “rock” wasn’t exclusively male in the post-girl group ‘60s. But its women—the most notable among them Janis Joplin, Grace Slick, Cass Elliot, Michelle Phillips, and coming up on the outside the Stone Poneys’ Linda Ronstadt—almost never played instruments. Yes there was San Francisco’s all-female Ace of Cups, wan in my reluctant judgment then and equally so in their recent revival, as well as the much livelier but still limited L.A. guitar band Fanny. But Joy of Cooking’s matched lead songwriters and canny sweet-gritty vocal interplay plus the way Toni Brown’s piano led Terry Garthwaite’s guitar over a three-piece male rhythm section rendered this a conceptually shrewd band with discernible feminist content in a time when the women’s movement was less than three years old. The polyrhythms point had weight—already the rock four-four could signify a dominance-and-submission dynamic metal was about to power up. And although I didn’t fully put it together until I reconceived my take on this album for the first Consumer Guide book in 1980, the songs had teeth: “The two protagonists are united by one overriding fact—they’re victimized as wives. And it’s about time somebody in rock and roll said so.”

Two personal notes. The first is that I wrote this piece during the nine months I taught at Cal Arts and lived in L.A.—and also often flew up to Berkeley to see my friends there. Thus I got to see the band, with a nudge from my pal Greil, infinitely more than I could have in New York, with the Long Beach show my narrative hook. The second is that I was thinking about women’s issues in rock and roll in large part because I’d spend most of the high ‘60s in constant communication with New Yorker rock critic and radical-feminist-in-waiting Ellen Willis, who’d been my girlfriend since well before rock criticism was a thing. We’d split painfully in September, 1969, and were in very sporadic contact thereafter. But when I initiated the Pazz & Jop Critics’ Poll at the end of 1971, she mailed in a ballot. Joy of Cooking topped mine, whereas—predictably, really, she was such a fan—her No. 1 was Who’s Next. But I was pleased to see that right behind it was Joy of Cooking.

Joy of Cooking is Berkeley-based and has gigged around Northern California—most often at a little club called Mandrake—for the better part of three years. It is led by Toni Brown and Terry Garthwaite, women in their thirties who are veterans of the Bay-area folk scene. Toni does most of the composing, plays keyboards, and sings harmony, counterpoint, and some lead. Terry is the lead singer and plays guitar. The other band members are men. Conga drummer Ron Wilson studied classical piano for twelve years and somehow ended up working with computers, a life he gave up at age thirty-five to join the group. Bassist Jeff Neighbor, who also plays violin and numerous other instruments, replaced Terry’s younger brother David shortly after the first album, Joy of Cooking, was released. Neighbor teaches music in the Berkeley elementary schools. Drummer Fritz Kasten has also played piano and alto sax. He has worked with Vince Guaraldi and with the San Francisco State Symphony Band. At twenty-six, he is the youngest member of the group.

A rock and roll fan is properly suspicious of such credentials. Creedence or no Creedence, Berkeley is an incestuous, self-righteous town blessed with an unparalleled concentration of mostly self-righteous talent. The far-from-adolescent protagonists of Joy of Cooking, with their roots in everything but rock and roll, could be predicted to turn out music that makes up in art, as they say, what it lacks in vitality, fun, and the common touch. Their album, however, is already moving up the trade charts, and when there’s a tour, it can be expected to break big. If it’s hard to imagine the band exciting young teen-agers, it’s not because the music is sterile but because Joy of Cooking is a very adult rock band. It’s adult, however, in the youthful way we try to be adult—without abandoning freshness and spontaneity—and so young teen-agers, who are not as predictable as older teen-agers like to think, can also dig it. After all, it has vitality, fun, and the common touch.

Toni Brown’s piano, which dominates, seems at first to fall into all the kitschiest traps. As a secret believer in the highbrow-lowbrow synthesis, I have always favored the straight-ahead barrelhouse boogie of rock and rollers like Little Richard and Chris Stainton or the more intellectual inventions of the great jazz pianists—the angular, reflective commentary of Thelonious Monk or the mad flights of Cecil Taylor—to middlebrow keyboard ticklers like Nina Simone, whose histrionic rolls insert unconvincing emotion into a song, or Les McCann, a leading proponent of self-conscious funk. But Toni’s resemblance to the middlebrows is only superficial. When playing for herself, she prefers abstractions like those of modernists Chick Corea and Keith Jarrett, but she’s smart enough to know that stuff doesn’t work in a band, and so she has stripped the pulp from the overripe Simone/McCann approach and come down to a clean core of rhythm.

Polyrhythms are really what Joy of Cooking is about. Ron’s congas are the best proof, but when you listen thoughtfully, you realize that Terry rarely takes a solo or even plays a lead line and that Toni’s one-chord improvisations work because they weigh about the same as the bass lines and drum patterns. Toni says the one rock pianist who has affected her is Stevie Winwood. This makes sense, but it’s not the kind of thing that occurs to you, because Joy of Cooking, unlike Traffic, is a disciplined band. Understanding that friendly polyrhythms can get boring, the group intersperses closely structured songs with stretched-out dance numbers. Toni switches to organ, Ron takes a harp solo, Terry plays lead for a chorus or two. Also, they sing.

For Toni and Terry to play lead instruments is an almost unprecedented breakthrough for women, but their success with vocal posture, where the precedents simply get in the way, is even more exciting. Basically, there are three kinds of female singer: the virgin, the sexpot, and her close relative, the sufferer. Each of these stereotypes suggest a human being who does not act upon the world, and the exceptions—little girl Melanie, for instance—usually play equally demeaning roles. Probably because the image seems closest to some metaphorical reality, most of the great women singers have been sufferers, but usually their defeat is so complete that even if they start out with a certain jaunty wit—like Billie Holiday—they end up hopelessly ravaged, and their occasional assertions of strength—think of Janis or Aretha—have a desperate edge. I can think of only two sufferers who have managed to project a relatively sure and consistent dignity: Bessie Smith and Tracy Nelson. Judy Collins and Joan Baez are dignified, of course, but at the cost not just of feeling but of corporeality. Partly because her looks—straight dark hair, big eyes, pretty face—fit the mold, partly because her voice is clear and sweet, Toni is close to the Judy Collins image, but the effect is modulated because she sits behind her instrument and because she shares the stage with a very different woman, Terry.

Terry’s unique power as a performer came clear to me the third time I saw the group perform, between a terrible macho-rock band called Robert Savage and sexpot Linda Ronstadt in the enormous Long Beach Municipal Arena. My previous experiences had been at the Mandrake, in Berkeley, and at the Troubadour, in Los Angeles, where the intimate circumstances favored the group’s quiet style. At Long Beach, especially in the wake of all that amplification, they seemed likely to disappear. Response was lukewarm to “Hush,” which had enjoyed some local AM air-play, and the next song was no better. Then the band went into an adapted folk medley of “Brownsville” and “Mockingbird.” To my astonishment, the intro elicited some spontaneous clap-time from the audience. Toward the end of “Mockingbird” Terry took the mike off its stand and began her scatting counterpoint with Toni. Then Terry began to scat alone. She has been described as a laid-back Janis. Her voice has that gritty quality, but she never screams, and what she abjures in power she makes up in subtlety. There is no better improvisatory singer in rock, but she gives the sense that it hasn’t been easy. Terry is a beautiful woman whose initial impact is mostly toughness; both her frizzed-out hair and something embattled in her face obscure its delicate bone structure until you get to know her. The sexuality she projected as she bobbed about the stage in Long Beach showed a similar reserve. It was self-contained, true to its own rhythms; it was sexual, not sexy, completely unlike the gyrations expected of chick singers who are getting it on. Yet the audience began to clap again, and the turned-on greaser next to me, who had been demanding an encore from Robert Savage half an hour before, turned and commented: “They’ve really got it together.” Could any band of women ask for a more miraculous compliment? Not yet.

Edgily, Toni and Terry insist that Joy of Cooking is not a band of women, and it isn’t. It’s an integral unit. But it’s led by women, and it seems to speak for them. Not long ago, Joy of Cooking preceded Barry Melton, the former Fish, at a small Bay-area concert. Melton is a good guy in his way, but he is a classic example of the white singer who tries to camouflage his racial confusion with a mask of phony black misogyny, and when he started to sing about gittin him four or five wimmin, he was booed to a halt. Such incidents have been rare, but they’re bound to increase. Whenever hard-core rock fans talk about their subculture, they forget how many brothers and sisters are left out of the consensus. Many vaguely feminist women have no special connection to rock not out of ideology but simply because it has never really spoken to them. Joy of Cooking can end that. Not that Toni’s lyrics are any more political, in the narrow sense of that term, than her stage demeanor. She is simply a literate female who has not been a girl for quite a while and who writes from the experience of trying to be her own person. Allow me to quote a long stanza as a kind of finale: “I used to think a woman was just made to love a man/That a man was someone for a woman to hold to while she can/And then one day my man walked out on me. Well, you know I got the blues./I’d been living off him for so long I had nothing of my own to lose./And now I’m gonna move,/Stretch out and find my wings and who I am/And if I ever pass this way again I’ll be ready for a good man."

If the women’s movement has taught us anything, it is that such realizations are political if anything is. It's enough to make you believe in art. You, and maybe the greaser next to you, too.