Starting in 1975, I saw Television perform many times, first at Max’s, where I was unimpressed, but mostly at CBGB, where early on they more than once shared weekend star time with David Byrne’s trio-then-quartet Talking Heads. Those double bills were the great prize of Manhattan music before both bands’ 1977 debut albums, Marquee Moon and Talking Heads 77 in February and September respectively, by which time I’d also caught Tom Verlaine’s band between John Cale and Patti Smith New Year’s Eve of 1976 at the Palladium. So the June 1978 Bottom Line Television gig described in the uncollected Village Voice review resuscitated for And It Don’t Stop below came 16 months and the follow-up album Adventure later and stands as a rather different account of the band than any album review could. Aesthetically above everything else, Tom Verlaine had principles, and live he acted them out. He was no hippie. But he respected his own self-created array of bohemian roots.

Television’s disappearance from Manhattan music over the past year and a half has emphasized their musical distance from the flourishing little club scene they helped create. For although they started out post-Velvets, and although “Blank Generation,” which now passes for an anthem at CBGB, began life as a showpiece for Television’s first bassist, Richard Hell, the term punk sits even more oddly on this band than on Talking Heads. At least the Heads remain committed to their own versions of two basic punk principles, brevity and manic intensity, but Television’s principles, as both admirers and detractors have observed, are throwbacks to the psychedelic era. These musicians are lyrical, spaced out, and obscure, and they don’t live in fear of boring somebody. Never mind the raveups and long solos—many of their intros, in which single riffs repeat again and again, stretch toward the one-minute mark, about where the Ramones begin the chorus.

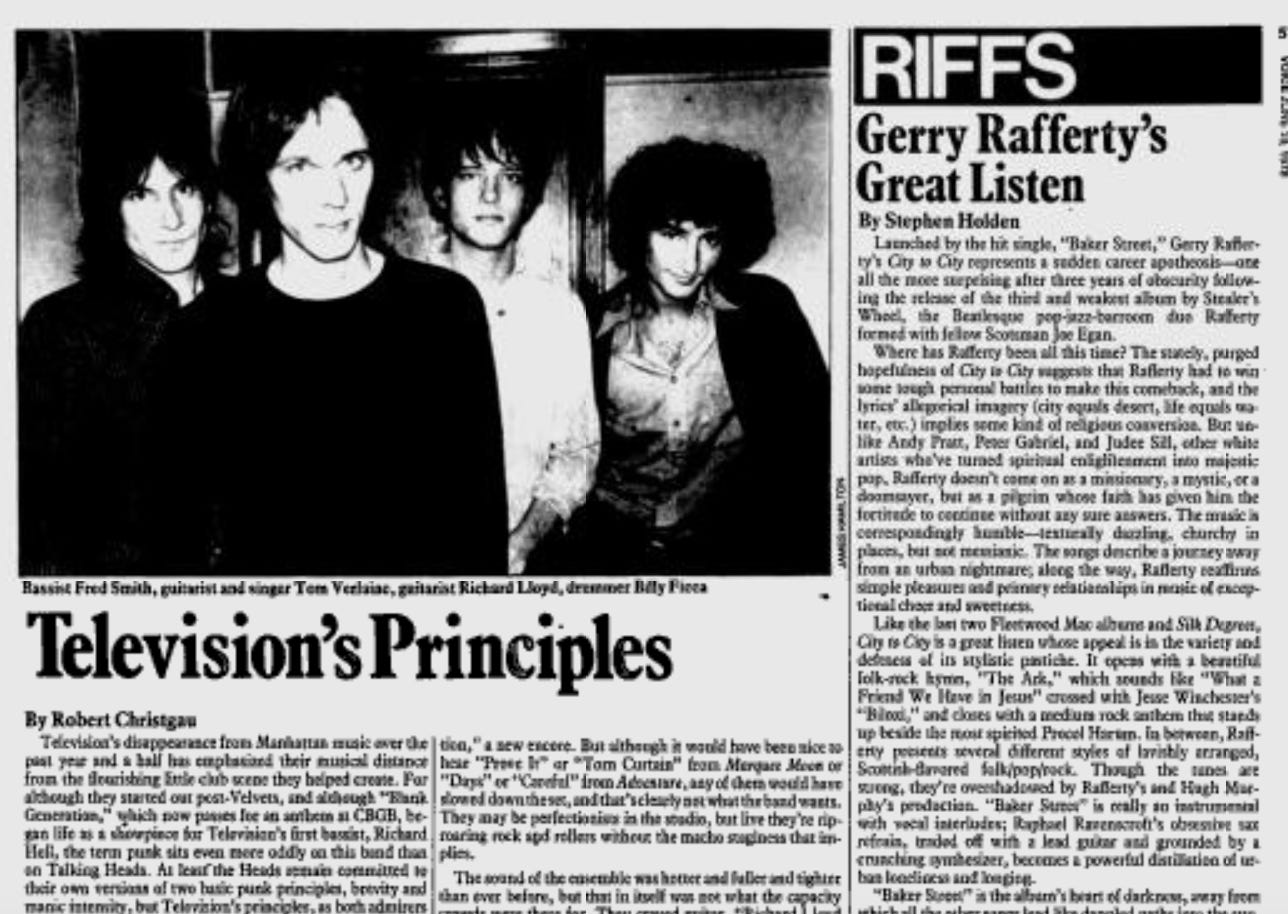

This is a strange kind of guitar band. The obvious forerunners are the Byrds and the Grateful Dead, even to Tom Verlaine’s long lead lines, which recall McGuinn and (especially) Garcia, although Verlaine’s attack is a lot rawer. The rhythm section of Fred Smith on bass and Billy Ficca on drums is very much into boom-boom-boom, and Verlaine and Richard Lloyd let their exertion show and do occasionally stumble or fuck up. Of course, if Verlaine doesn’t seem facile enough for folk-rock prettiness or bluegrass ripple, or if Lloyd, his slashing counterpart on rhythm, seems unprepared for one of those blues-sustain showoff numbers that every hard-rock hotshot is supposed to have at hand, it only means that there are a lot of clichés out there that they’ve never even bothered to learn. But people who like guitar bands rarely have the ears to hear it that way.

If Television aren’t slick enough to suit the virtuoso vultures, neither are they ruff ‘n’ tuff enuff for doctrinaire rock and rollers. Those who know the band only by their albums often dismiss Verlaine as a wimp, and complaints about thin recording on Marquee Moon have turned into charges of bland-out on Adventure. Me, I think the two albums are pretty much of a piece, although I prefer Marquee Moon because it rocks harder, and agree that Verlaine’s newer compositions seem rather reflective. I mean, I too am in this for the rock and roll. I don't ask much from life—a classic new rhythm guitar figure at medium-fast tempo like the one on “See No Evil” can keep me going for months. When the call-and-response chorus of the song that follows peaks at a perfectly timed “Huh?” I begin to act silly. And when two consecutive albums, eight songs each, offer a total of 16 unmistakable ident riffs, I apply hyperbole first and ask questions afterward. So okay, I probably like the Ramones better. But not even Tommy Ramone’s farewell gig at CBGB last month had me shouting for more like the first of the two Television shows at the Bottom Line Sunday.

If these be wimps, they’re the loudest wimps I’ve ever heard; their notorious diffidence has been well modulated since they began to tour in 1977. Verlaine’s stagecraft is about what it’s always been—he rolls his eyes upward to indicate effort, exhilaration, amusement, or surprise—but he grinned openly on more than one occasion and like his bandmates seemed to have gained some looseness up there. To my disappointment, the two sets were very similar, incorporating eight selections from the albums plus “Little Johnny Jewel” and two covers—“Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door,” an old standby, and “Satisfaction,” a new encore. But although it would have been nice to hear “Prove It” or “Torn Curtain” from Marquee Moon or “Days” or “Careful” from Adventure, any of them would have slowed down the set, and that’s clearly not what the band wants. They may be perfectionists in the studio, but live they’re rip-roaring rock and rollers without the macho staginess that implies.

The sound of the ensemble was hotter and fuller and tighter than ever before, but that in itself was not what the capacity crowds were there for. They craved guitar. “Richard Lloyd could play lead in any band in the country but this one,” someone yelled, and Lloyd proved it during his first-set solo on “Ain’t That Nothin’,” which climaxed with a simple climb-the-scale raveup that he pulled tighter and tighter, shedding stray note-clusters as he advanced. That remained the best guitar I’d heard all year until about 25 minutes later, when Verlaine launched into a portion of the “Marquee Moon” solo that was so eerie and airy and out of this world he could have been playing bagpipes. Many of the band’s most exciting touches are as prearranged as their song structures—when Lloyd began to wrench distortions out of a loose string during the first-set encore, I concluded that he was just pissed at tuning problems, only to watch him repeat the move at the close of the trouble-free second show. But both men really do improvise, and whatever they forsake in the way of bullshit chops, their melodic and rhythmic inventions are dexterous indeed.

One nice thing about these shows was that I got most of the lyrics. This was because I’d more or less memorized them from the records. Especially on stage, Verlaine’s pronunciation is as twisted as his voice itself, and although to me both just seem like good old Tom, I can see how it might be hard to figure out who Tom is without being able to understand the lyrics. Not that knowing the words is knowing what they mean—as Verlaine himself puts it in his ambivalent paean to rationality “Prove It,” many of them are “too ‘too too’/to put a finger on.” His writing is genuinely idiosyncratic and spiritual, and although he’s more humorous and dreamy on the new record, he stated his credo right after that classic riff at the beginning of Marquee Moon: “What I want/I want NOW/and it’s a whole lot more/ than ‘anyhow.’”

Verlaine’s needs and visions are deep-seated and obsessively personal; I wonder if even he knows what “Marquee Moon” is about any more. He’s such a bourgeois individualist he even changed his credo to “and it’s a whole lot more/than Chairman Mao” one time Sunday night, and I say good for him, because I believe he’s ready to risk all in his quest. The line that haunts me from the new album—“I love disaster and I love what comes after”—could be a revolutionary’s motto as easily as a mystic’s. In this denial of limits, asserted as well in the musical release they aim for, Television is representative of nothing. Almost every great rock band and many of the most successful bad ones culminate some general social tendency, be it the Ramones’ pop economy or Kansas’s greedy middle-American pseudo-seriousness or Steely Dan’s expert programmability or Kiss’s life-sized caricature. But while it’s possible to imagine a late-‘60s revival in which Television would spawn countless imitators, at the moment their single-minded utopian individualism sets them apart. And it is just that that makes them seem so precious.