The Big Lookback: Stevie Wonder

From 1999, written for the program to the Kennedy Center Honors induction

The Kennedy Center Honors began in 1978, which puts Stevie Wonder’s 1999 award around their midpoint from now. At the time he was the 21st awardee from a popular music conceived to encompass jazz, gospel, and Broadway as well as “rock”—11 Black and 10 white, if you’re curious as I always am, with Chuck Berry and James Brown to follow in 2000 and 2003 and no year after 2002 destined to include fewer than two pop musicians rather than the one per year that was standard before then. Most egregious omission: Miles Davis. Oddity: not just emigre Elton John but surviving members of the Who and Led Zeppelin have all been Kennedy Center honorees.

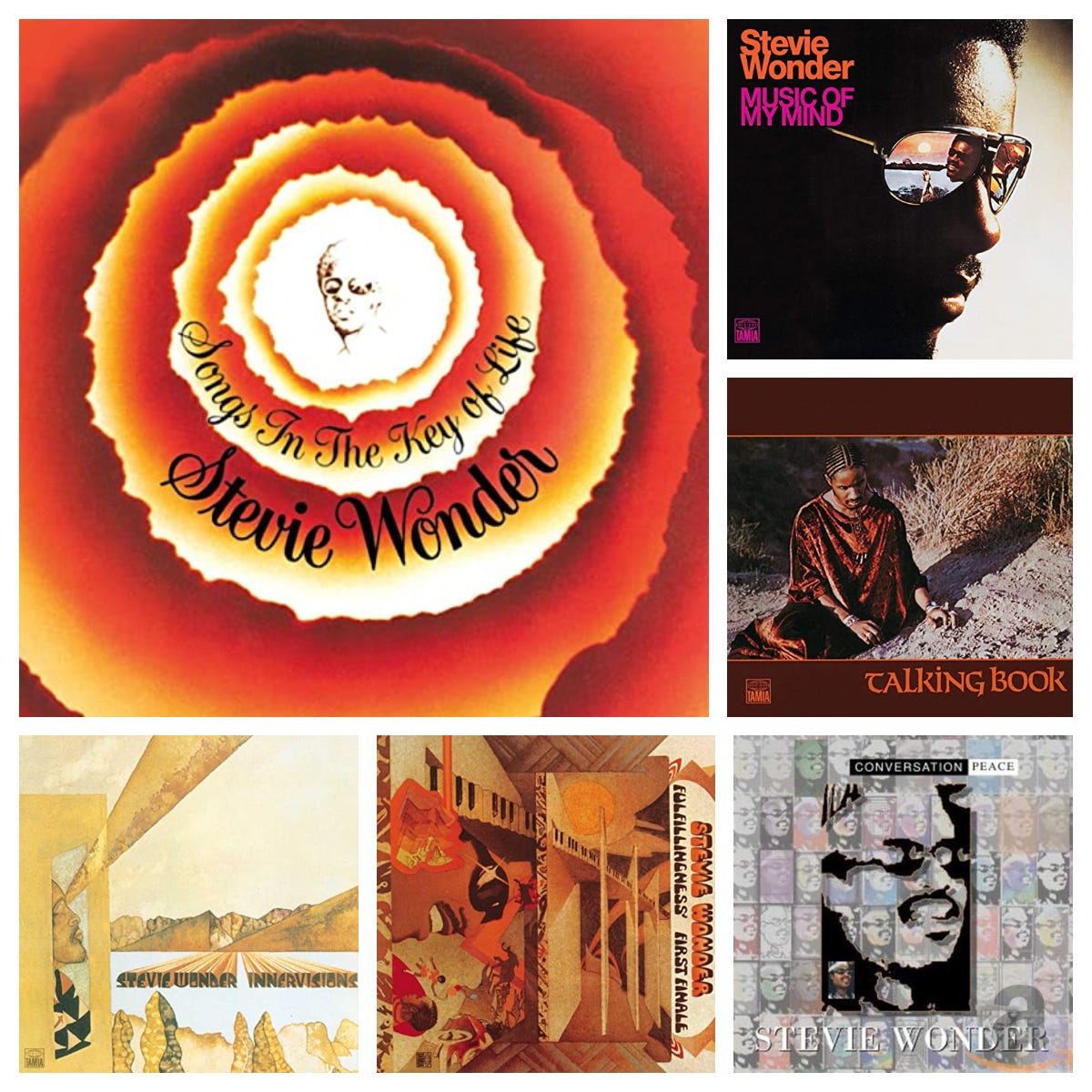

Exactly why I was asked to write Wonder’s appreciation I don’t recall if I was told at all. Maybe it was the Stevie diptych in my just published Grown Up All Wrong, which combined 1974 and 1976 Village Voice essays titled “Stevie Wonder Is a Fool” and “Stevie Wonder Is a Masterpiece” under the header “Stevie Wonder Is All Things to All People.” Like all Kennedy Center Honors, Wonder’s was very much a lifetime achievement award—his only album of new songs in the ‘90s was 1995’s Conversation Peace, which when I played it for the first time in decades as I began to write this seemed worthy of its A minus to me, not least but far from solely because its title song includes the line “Like in the Holocaust of six million Jews and the 50 million Blacks during slavery.” But clearly the ‘70s were Wonder’s creative heyday. And so what I wrote was designed to account for the fact that despite his tumultuous ‘70s his most famous song—more famous than even his three galvanizing mid-‘70s protest smashes, two of them number ones, “Superstition,” “Living for the City,” and “You Haven’t Done Nothin’”—was 1984’s de facto AT&T commercial “I Just Called to Say I Love You.”

These days the 71-year-old Detroiter born Stevland Hardaway Judkins probably seems anodyne to some. In deep retrospect it may be hard to comprehend much less feel what a game-changer he was. So I hope what I wrote for the Kennedy Center and expanded on here makes that a little clearer—his rebellion against Berry Gordy was epochal, and his racial reach was a wonder. To this day very few Black artists have broached the hit parade with music that fused racial pride and humanist tolerance with such seeming ease. But I’d like to add two details my appreciation barely brushes against.

One is that as late as 1972 Wonder was pursuing the rock audience by taking the stage at modest rock venues unsuitable for chart-topping artists, Black ones especially—in February of that year I wrote an inaugural Newsday column that included his unlikely gig at Bleecker Street’s Bitter End. The second is that in August of 1973, Carola and I were driving around Los Angeles when over the car radio came news that a serious automobile crash in North Carolina had left Stevie Wonder unconscious and hospitalized with no prognosis yet available. Instantly I pulled over and the two of us sat shaken in the shade of a residential street. Would he survive? We had no way to know, but it sounded bad, and we needed to absorb what it might mean. Because for us Stevie Wonder represented possibilities for rock and roll, political possibilities in particular, which if they didn’t die with him would certainly be set back. Although it’s likely MLK Day would never have become a national holiday without him, you could say we were overreacting. But whenever I think about what became of Stevie Wonder, I always remember how much he meant to us in that moment.

Stevie Wonder is such a pop icon that it’s hard to remember the risks he took and the possibilities he opened up. Maybe we suspect our impression that the course of his career was as inexorable as the sometimes placid, sometimes turbulent river of melody that is his music. We know things are never that simple. But Wonder is so multitalented that it’s easy to ignore the difficulties he had to overcome. His greatest gift of all would seem to be his constitutional unwillingness to take no for an answer.

Unlike Ray Charles, who was sighted until he was seven, Steveland Judkins Morris was blind from birth, probably due to an accident in the incubator where he spent his first month. Yet his family sent him to public schools in Detroit’s East Side ghetto, and by 1960, when he arrived at Motown at age 10, he could already play piano, harmonica, and drums—synthesizers hadn’t been invented yet. This is impressive enough, obviously. But what’s even more remarkable is that he survived one of the most crippling ordeals of American show business—child stardom. At a label notorious for holding artists in thrall, the prodigy Berry Gordy dubbed Little Stevie Wonder managed something like a normal rebellious adolescence, which included integrating a Bob Dylan song and a Charlie Watts beat into the Motown formula on separate 1966 hits. And when he turned 21 he asserted himself with a force whose repercussions still echo through the music industry. After voiding the contract he’d entered as a minor, he re-signed with Motown in 1971 and again in 1974 on terms that guaranteed total creative control and unprecedented levels of reimbursement.

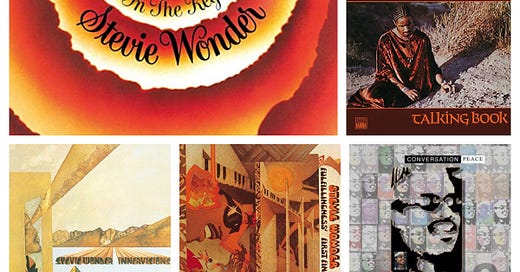

For Motown and the world, the payback was instantaneous and monumental. In the first five years of these contracts, a period marred by a near-fatal automobile accident, Wonder released five albums: Music of My Mind, Talking Book, Innervisions, Fullfillingness’ First Finale, and Songs in the Key of Life. Musically, this sequence stands alongside the miraculous outpourings that have marked the careers of Bob Dylan, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Aretha Franklin, Al Green, and George Clinton. Less miraculous, because Wonder knew exactly what he was doing, it also reshaped how he was perceived. Wonder started cowriting his hits at around 17, and his chart success was unabated in the years just preceding his rebellion. But it was a few showcase performances at small rock clubs, capped by a canny decision to open the Rolling Stones’ 1972 U.S. tour, that established his claim to the autonomy and virtuosity that were preconditions of credibility with the album-buying audience. So not only did his top 40 presence intensify, but suddenly the music surrounding the hits was heard by many millions instead of a few hundred thousand.

Almost everything about this music was an amazement. Melodically, Wonder’s simple eloquence was a worthy continuation of an endangered Tin Pan Alley tradition. Rhythmically, he hit upon his own version of the funk then being developed by James Brown and lesser mortals, here more fluid and there more jagged than the soul and rock he straddled so unabashedly. Vocally, his slightly nasal high baritone, rare in black pop for how little it owed the church, exerted an enormous influence on a coming generation of comic funksters and African-American matinee idols. Instrumentally, he proved an early master of the synthesizer he laboriously and prophetically learned to play. Technologically, he was king of the overdub, playing all the parts in the studio and achieving a naturalness of feel matched by no other one-man band except his great heir Prince. And philosophically, his music evoked the universalism some found dubious in his public pronouncements. It embraced soul, r&b, rock, pop, jazz, and the whole African diaspora—just this year he shared a New York stage with the Senegalese singer Youssou N’Dour. Moreover, as the classically tinged 1979 Journey Through the Secret Life of Plants announced, Wonder had no intention of stopping there.

Since 1980, Wonder has been less fecund, although his output includes two impressive soundtrack collections, some world-class rhythm workouts, and many tuneful ballads, most prominently “I Just Called To Say I Love You,” a broad-spectrum shout-out that spoke to the shared experience of more potential listeners than anything Irving Berlin ever wrote. He doesn’t appear in concert much either. But beyond his rhythm things and silly love songs, Wonder has always made it a point to address social questions in song—urban poverty, black history, Vietnam veterans, handguns—as well as campaigning actively around such issues as apartheid and world hunger. The cause he made his own was the national Martin Luther King Jr. holiday, which it is fair to say might never have passed into law without his efforts. Like Dr. King, he remains a national treasure, a beacon to the African-American community who challenges received values more unrelentingly than his benign reputation suggests. He proves that even at its most accessible, great pop music can enlarge those who care about it.