The Big Lookback: Rock 'N' Revolution

Thoughts on John and Yoko, the MC5, People's Park and the difference between changes in style and structure, from 'The Village Voice,' July 3, 1969.

“In the worst of times, music is a promise that times are meant to be better”—way back in 1969 one of the best sentences I’d ever write. So I was proud when my old friend Greil not only singled it out in an 80th-birthday Zoom the Pop Conference organized for me but let me publish his comments as a guest post here. And I was struck when Joe Levy mined Google News for art and found the original of “Rock ‘n’ Revolution,” the July Village Voice column where the sentence appeared—including an italicized intro that got dropped when it was collected in Any Old Way You Choose It in 1973. Though “Rock ‘n’ Revolution” isn’t much of a hed in any case, the intro is self-indulgent at best and it was right to drop it. I’m reproducing it here because it has documentary value half a century after the fact: “BEING . . . a kind of sequel to my ruminations on Bob Dylan, the MC-5, and off hand reply to (off) Lucian Truscott IV and (off) Jac Holzman, and a belated thank you to (National) Guardian editor who once entitled a piece of mine on Country Joe & the Fish ‘Rock 'n Revolution.’”

I have no recollection of putting the “In the worst of times” sentence on paper—it strikes me as the kind of thing that after some rumination pops into your head pretty much whole. But I do recall writing the essay it appeared in because it took a full week—300 words a day, slow even for me. Having been offed in January by Esquire, which was paying me $500 a column four times a year, I’d made my decision for rock criticism in February by securing a monthly column at the Voice, which paid $40, a sum so measly I decided to revisit my college days and crush out all-nighters: March’s inaugural “Gap Again” about “genres” labeled “bubblegum” and “white blues” fragmenting a rock audience we’d conceived as a single rebel “counterculture” into age-based cohorts, April’s “Kinks Kountry” advocating for the obtusely under-reviewed The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society. Although June’s MC-5 column also has a rushed look, May’s thoughts on Nashville Skyline are so sharp I doubt I all-nighted them (this was Dylan, after all). But both address the kind of political themes that are the subject proper of the July column reproduced here, which marks the moment when I clearly made up my mind to exploit the freedom the Voice afforded its contributors in lieu of cash and write with an ambition worthy of my relationship with New Yorker rock critic and nascent feminist intellectual Ellen Willis, with whom I’d shared years of ongoing political conversation that inspired me to use my Voice platform to put my own stamp on issues we’d gabbed about obsessively for years.

And so I spent a steamy week laboring over a 2500-word essay about a John and Yoko just then embarked on their give peace a chance campaign and an MC-5 whose sexism I’d rushed past in June. But fueling my sense of urgency was People’s Park, a cause celebre now faded from memory that saw California governor Ronald Reagan brutally but in the end unsuccessfully attempt to crush a movement to convert a modest parcel of University of California real estate into city property everyone in Berkely could use. In this matter my chief informant was Greil Marcus, with whom I was corresponding profusely though we hadn’t yet met in person. The poet I quote toward the end is the late Todd Gitlin, who by Any Old Way You Choose It time was so unhappy with what he’d written he OKed the reprint on the condition that I not put his name on it.

The so-called “Rock ‘n’ Revolution” represented a turning point for me as a writer. Although I kept my still nascent Consumer Guides coming in July, August, and September, in late September Willis and I broke up so traumatically that it would be December before I published in the Voice again: a long overdue Consumer Guide, but first a musical diary infused with the breakup called “In Memory of the Dave Clark Five.” My Voice writing had changed as I put serious time into exploiting its platform in many disparate ways, most decisively with the two-part September 1970 opus “Living Without the Beatles,” which at bottom was also about the breakup—and which inspired a job offer from Newsday. In August of 1974, that career move led me back to the Voice, where as music editor I spent a decade writing as ambitiously as I was just starting to in “Rock ‘n’ Revolution”—and seeking out other writers eager to do the same.

A riddle for you.

Q.: Why is rock like the revolution?

A.: Because they’re both groovy.

Now, I am aware that this is not the standard argument. Rock and roll, as we all know, was instrumental in opening up the generation gap and fertilizing the largely sexual energy that has flowered into the youth life-style, and this life-style, as we all know, is going to revolutionize the world. Well, not exactly. A noted commentator on such subjects, Karl Marx, once observed: “A revolution involves a change in structure; a change in style is not a revolution.” In that sense—rejecting any optimistic projections about how small changes in style can transform structures incrementally—rock is clearly not revolutionary at all. The other kind of revolution—the kind that permits Columbia Records to call its artists The Revolutionaries—is a revolution in style. It can make nice changes for people, yes. But all that means is that it’s groovy.

The fact that a small minority of young politicos actually understands this only proves how drastically the politics of generation has outstripped its own origins. Without doubt, the way rock and roll intensified youth consciousness was a political phenomenon—that is, it affected the power people had over their lives. In fact, there was probably a time when rock could be called, without too much hyperbole, the most socially productive force in the Western world. It educated kids to ways of living that their approved education glossed over, and it provided a bond for the young and the youthful. But even though something of the sort is still happening, the formal precocity of rock—the rapidity with which it expanded and too frequently exhausted itself—distorted its political usefulness. As the best performers elaborated their music, they narrowed their audience, and too often the gospel of sexual liberation and generational identity became a smug ritual, with the wider audiences left to the lifeless myths of the schlockmeisters the rock artistes deplored.

Anyway, the new youth gospel was greeted with unanticipated hostility by the old capitalists, who still had most of the power, and there was precipitous escalation, most of it rhetorical, on both sides. Suddenly, sexual liberation and generational identity (together with expanded consciousness, a last-minute attraction) were understood by both sides as facets of an inevitable social upheaval. It was all the same big revolution. But was that what Danny & the Juniors meant when they told us rock and roll was here to stay?

This all happened very fast. Politically, it was facilitated by a vanguard of real revolutionaries, traditionally political in outlook but with strong youth ties, who tried to structure and define the anarchistic unrest of the heads, turning it away from that confusion of style and structure which Marx deplored. In the intoxification endemic to youth politics, both the politicos and the heads tended to overestimate the dedication and numerical strength of their troops. Launching their movement from a position of moral superiority that seemed compelling in an environment of liberal tolerance, the youth leaders made the old elitist assumptions and waited for the movement’s constituency—with a healthy push from the culture and especially the music—to organize itself.

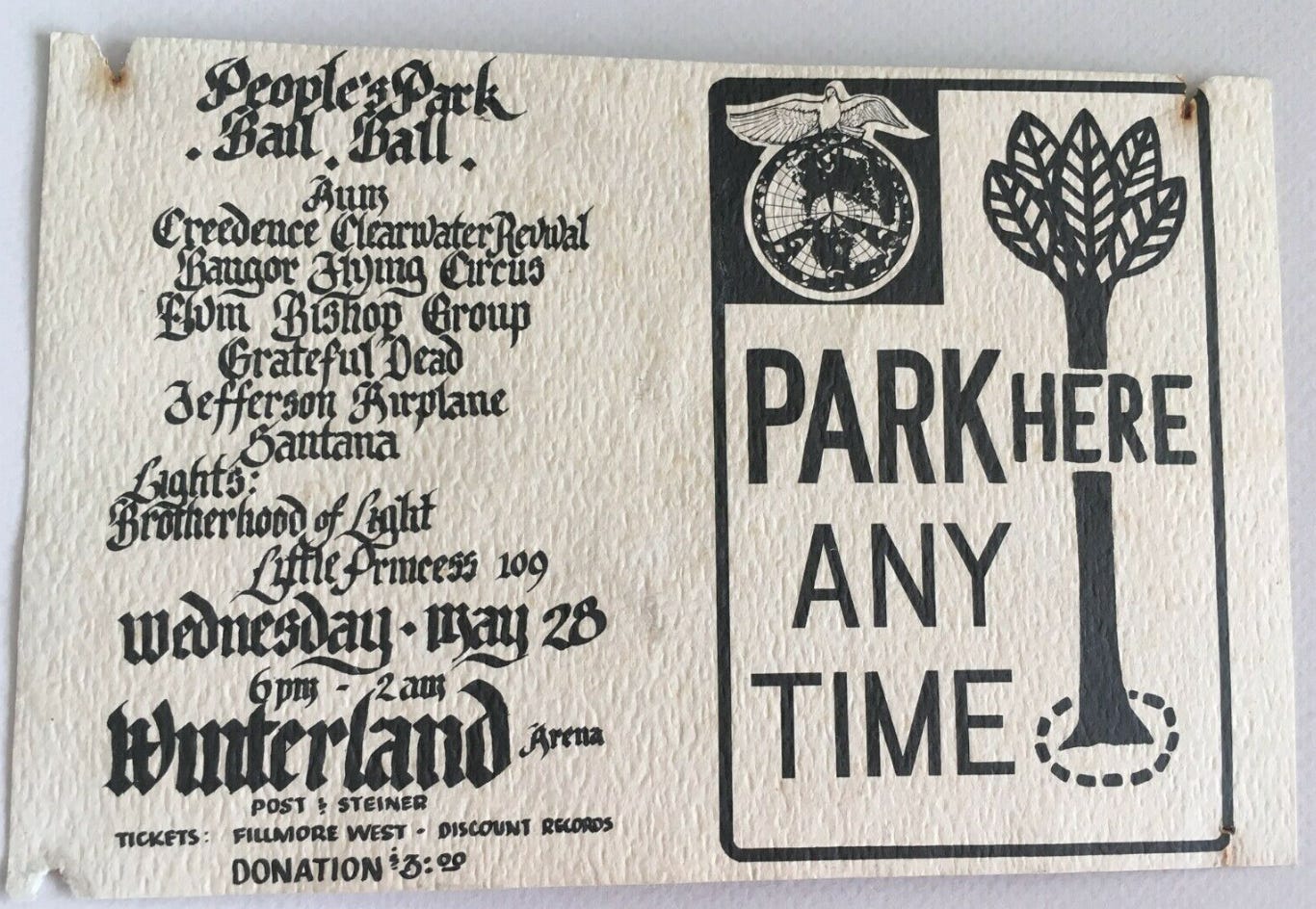

In the wake of People’s Park, many activists in the Bay Area, an especially intoxicating stronghold, believe this has actually happened. People’s Park represents an excellent departure from the abstract politics of the past few years because it is an issue with broad, concrete, and self-evident appeal that embodies a radical concept, the inhumanity of institutionalized private property. In other words, it combines the groovy revolution with the structural one. It is significant that rock groups are working for People’s Park (Bill Graham sponsored a bail benefit at which the Airplane, the Dead, and Creedence Clearwater appeared) when they don’t move for the Panthers or the Chicago Seven.

It ought to be remembered that musicians have never tried to be in the political vanguard—whatever their metaphorical proclivities, artists usually like peace and quiet as much as, if not more than, anyone else. The musicians never called for revolution in the first place, only certain of their fans. It took about eighteen months—from early 1967 to late 1969—for the idea of “revolution” to evolve from an illusion of humorless politniks to a hip password that, like everything hip, was promulgated free (both vitiated and made more dangerous) by magazines, networks, and even advertising agencies. The hype, as we in the music biz call it, imbued the movement with an apparent strength that intensified its infatuation with itself. There are still many would-be revolutionaries who talk about full-scale wish-fulfillment by 1975.

That is extremely unlikely at best. After all, People’s Park also has a rather decisive negative side. As of now, the people (a term that for once is relatively accurate) haven’t even gained their park, much less established their principle, and the relative lack of concern east of the Sierra Madres has been appalling. White Americans haven’t suffered such terrorism—arbitrary gunfire, torture, martial law—since the worst labor battles of the ‘30s. Why hasn’t there been more outrage, more solidarity? Can it happen here (and in Iowa? Florida? Vermont?) only when an equally concrete issue is created?

I’m afraid there may be another answer. I’m afraid that many people—not only the grown-ups, whose apprehension seems to increase geometrically with every new atrocity, but also almost all the kids—are very chary of the revolution. The reason is simple: Real revolutions are unpleasant, not groovy. You can get killed and everything. And so caution is more than justified, especially in the face of overwhelming odds. The most important drawback to the revolution of 1975, after all, is that the other side wins. All revolutions are unpleasant, but the ones you lose are really for shit.

But it also seems to me that it is cowardly to worry too much about such details—if it happens, it happens, and everyone chooses sides. All of John Lennon’s rationalizations are correct. Violence does lead to more violence, and the tedium and rigidity of effective politics are antihuman. But Lennon would never have achieved enlightenment if thousands of his forebears hadn’t suffered drudgery far worse than protest marches and cared enough about certain ideals (and realities) to risk death for them. (Three hundred years ago, a snot like Lennon would have had his hands cut off by the time he was thirteen—although, come to think of it, his sense of exactly how far he can go is so uncanny that he might well have survived and prospered. But what about Ringo?) It really does get better all the time—a little better—but that doesn't mean that it’s perfect, or that it’s going to continue. (John and Yoko have suggested that people in India starve because they’re afraid to migrate. That’s literally what they said.) Anyone who is serious about changing things ought to be willing to prove it by taking risks. Right now, that means engaging in what I would call prerevolutionary politics, politics that test the system’s vaunted flexibility. It means finding out now whether imperialism, racism, sexism, the destruction of the ecosystem, and the robotization of human life (not to mention trivial problems like military slave labor, starvation, and organized crime) can really be ended without overthrowing the state. It means accepting the labor of organizing now and remembering that violence may be necessary later, not as catharsis but as tactic. And it means being ready to give up your comforts if things turn out to be as bad as they seem.

It does not mean that every musician should give himself to the movement. Art and politics rarely mix, and good music is always good for the world, which is finally what politics is about. A revealing musical iconography has developed around People’s Park. After John Lennon rang to remind everyone to keep it nonviolent and to muse a bit about moving the action away from Berkeley because the waters were troubled there—thus firming up his newfound status as a pompous shit—“Don’t Let Me Down” was used as an anthem by some of the Memorial Day marchers. The Dylan picture from Nashville Skyline was reproduced without comment in emergency newspapers published in Berkeley during the crisis. To an extent, this is self-indulgent fantasy—all the good guys are really with us. To an extent, it is a calculated marshaling of potent symbols, much the way the park itself was marshaled. But it also had its own validity. These politicos genuinely loved music. They recognized that John Lennon knew something about commitment even if his politics were fatuous, that Bob Dylan had achieved a kind of serenity that all of us might someday like to emulate. Perhaps the best demonstration of this approach to music is three lines of a long agitprop poem by a veteran Bay Area activist called “Berkeley, May 15-17, 1969”: “O my God they’re shooting! Hardly anyone is blinded. Many people die./ Many women are born, and men seeing for once as clearly as women./ Keep running. Breathe even. Listen to the Band when you can.”

In the worst of times music is a promise that times are meant to be better. Ultimately, its most important political purpose is to keep us human under fire. John Lennon and Bob Dylan, both of whom seem to sing their best when they are thinking their worst (“The Ballad of John and Yoko,” “I Threw It All Away”), are often better at keeping us human than trusty propagandists like Phil Ochs—I wish I could add another name, but singing propagandists are rare these days.

Still, we don’t just respond to music—we respond to what we know about it. Rock is good in itself, but it is also good because of what it does for people. We have always loved it for political reasons; the praise of vitality, after all, is a populist judgment. And at this moment in history politics are an index of vitality. It is puritanical to expect musicians, or anyone, to hew to the proper line. But it is reasonable to request that they not go out of their way to oppose it. Both Dylan and Lennon have, and it takes much of the pleasure out of their music for me. After shrugging off the Maharishi, John is bidding to take his place. If only his bed-ins would turn Nixon around a bit—Trudeau, even—his foolishness might seem sainted. As it is, they merely provide one more excuse for a lot of good kids to cop out. Dylan’s apostasy is more subtle. He has a political past, so his opposition doesn’t have to be explicit to be deeply felt. It may be that country music is beyond politics, although it does serve rural culture as a buffer against the incursions of new (especially black and urban, but also young) ways of doing things, and although it obviously flourishes among populist conservatives. In any case, Dylan’s embrace of country music, especially considering his always acute attention to stance, is political indeed. A year and a half ago, remember, Dylan released his most political album in years, John Wesley Harding; he also put in a rare public appearance at a Woody Guthrie memorial. Now, after Nashville Skyline, he guests for Johnny Cash, an enthusiastic Nixon supporter.

I know much of this is going to be misconstrued, so let me try to be more explicit. I am not putting down Johnny Cash’s music because he likes Nixon, or Dylan’s because he likes Cash, nor am I suggesting that Dylan endorses Cash’s politics by participating in his music. I’m not even dismissing Cash’s politics. There are good reasons for conservatism, and I suspect Cash is sensitive to most of them; Dylan certainly is. That does not mean, however, that either is right. I enjoy and admire and learn from their celebrations of individualism and the simple life, but I remain aware of their limitations. In the case of Dylan, and Lennon, the limitations become really distressing because I know each is capable of much more. Furthermore, I think my reservations are aesthetic. What I really don't like is softheartedness. “Revolution” is as artistically indefensible as, oh, “Love Can Make You Happy,” and for many of the same reasons.

For similar reasons, I like the MC-5. I like them even though I think their political position is rather dumb, based on an arrantly sexist analysis. The new pop has managed to discard a lot of myths, but because male supremacy is rarely perceived as the political issue it is, because it is on the contrary often taken as folk wisdom, most popular music works to reinforce the existing system of male-female relations. The 5, however, go much further than that. Rob Tyner mock-rapes random girls as a standard part of his act. John Sinclair claims that the groupies who journey to Ann Arbor to fuck the 5 act as energy carriers, disseminating the revolution (and the crabs?) all the way from Lansing to Grosse Pointe—implying, of course, that these females have no revolutionary energy of their own. It is even possible to take the group’s incessant revolutionary rhetoric—a rhetoric that as usual obscures real problems and alienates those who are to be organized—as an expression of machismo. But for the next few years the password for hip politics (which means rock politics) seems likely to be revolution-now. Since the 5 are courageous enough to push in that direction, I want to relate to them—though it helps that I also like their music.

I think people who reject the 5—even if they object in terms of the music, which emphasizes the violent, low-life aspects of rock that the art-subtlety-taste crowd would just as soon ignore—do so for political reasons. “They’re trying to shove the revolution down everyone’s throats,” one kid has complained to me. Of course, he’s right. The 5’s methods have been very crude. If they don’t respond to real needs within their apparent (and their music) to achieve the popularity they want, then they will have failed, artistically and politically.

For that is the final irony of rock ‘n’ revolution. The political value of rock is a function of how many people it reaches, yet as rock becomes more political, it reaches fewer people. Almost everyone knows this, but no one knows what to do about it. John Lennon has scored a lot of points off the “snobs” who run the radical movement in this country—God knows he’s right about that, anyway—and his methods, which have their similarity to Jerry Rubin’s, demonstrate that he is serious. The Left does need new methods, new styles. Only it’s not clear that the Lennon-Rubin methods are effective, either. In fact, all that really seems clear is that no matter how much you want to change things, it sure is hard to do.