The Big Lookback: Randy Newman

"Irony, Compassion and Randy Newman," from Newsday, October 29, 1972

Although I no longer recall when I first got wind of Randy Newman, I do remember who first assigned me to write about him—Russell Sanjek, a sweetheart of a veteran pop music journo whose laborious three-volume American Popular Music and Its Business I panned respectfully, regretfully, and posthumously in 1989. I met him circa 1969, around the time I was transitioning from my Secular Music column at Esquire to Rock & Roll & at The Village Voice, when as editor of the BMI house mag he asked me for a one-page brief about this up-and-coming Newman fella whose eponymous 1968 album, if I’m lucky enough to have the timeline right, I already admired, and whose 1970 12 Songs I was destined to give an A plus. So I interviewed Newman in his modest Studio City corner house, after which we played one-on-one basketball in a nearby park. Although he had several inches on me, I did hustle some rebounds. Sad to say, I don’t remember who won.

Unfortunately, that BMI piece hasn’t surfaced in my files. But Newman and I had gotten along fine, and when he came through New York in the fall of 1972, when I was well into my tour as the pop music critic at Newsday, I was more than happy to beef up a critical piece with an interview, not normally my preferred m.o. Note FYI that my sole review of Tom Rapp’s Pearls Before Swine went “I never understood who they/he were/was throwing their/his accretions at/before” and that my David Ackles C minus read “‘I won’t get maudlin,’ Ackles promises midway into the second side, locking himself in the barn as the dappled stallion gallops to join his brothers and sisters on the open range with his mane flying free in the breeze.” There were certainly much better singer-songwriters than those two saps, including a few L.A. buddies who Newman would hook up with occasionally throughtout his career. But because that was the kind of treacle too many late folkies trafficked in, it was gratifying to resort to Newman as their opposite number even if it was too bad that his very excellence seemed destined to keep him off the singles chart.

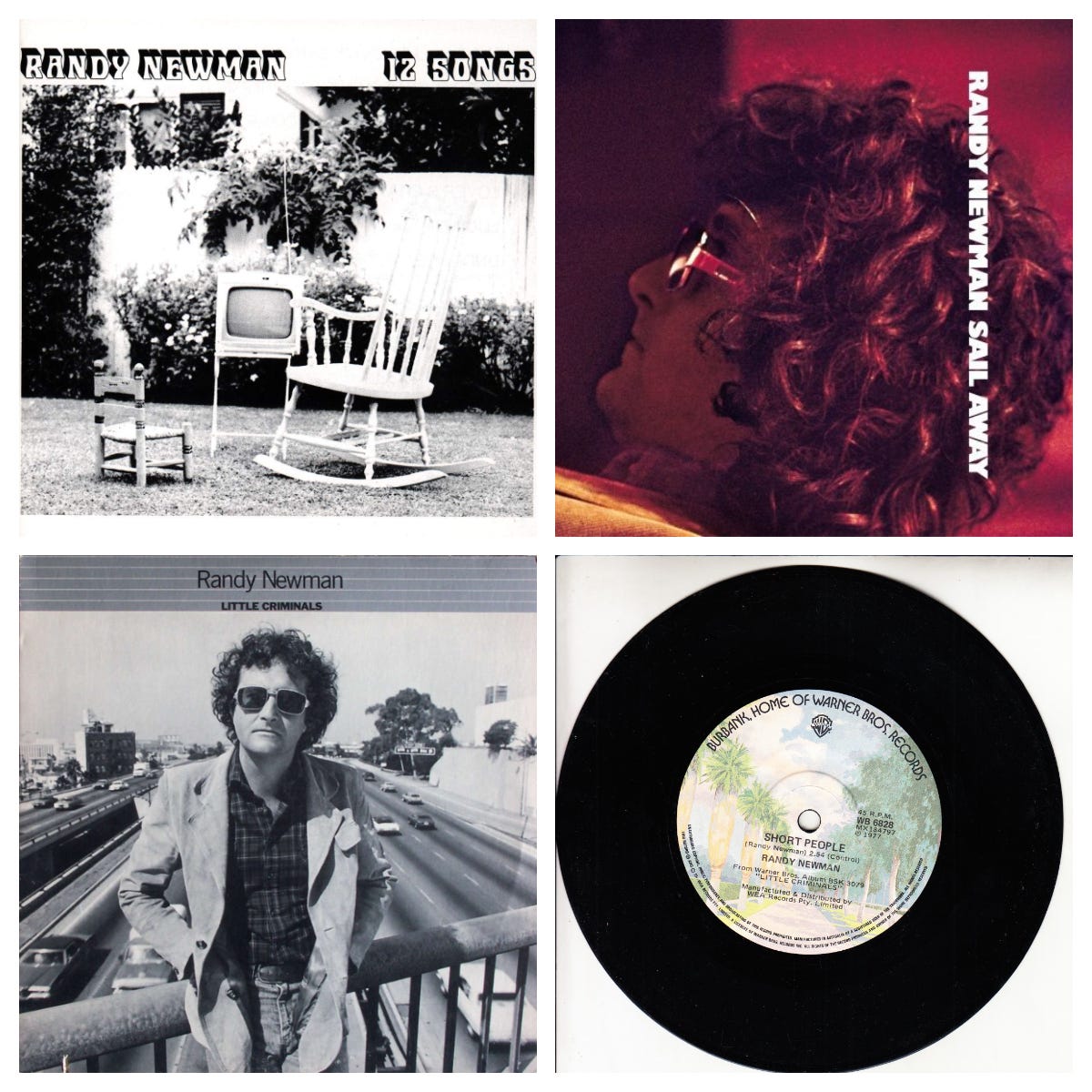

Only then in 1977, the year of Newman’s fifth studio album, Little Criminals, he hit gold with a supercatchy little novelty song called “Short People” that disparaged all human beings of subnormal stature: Though according to Wikipedia it was “intended by Newman as a satire on prejudice more broadly,” it kicked up quite a fuss as it rose to number two in Billboard, a fuss Newman himself claimed offended “only a tiny minority.” In case you’ve forgotten or never knew in the first place, it went like this:

Short people got no reason

Short people got no reason

Short people got no reason

To live

They got little hands

And little eyes

And they walk around

Tellin’ great big lies

They got little noses

And tiny little teeth

They wear platform shoes

On their tiny little feet

Well I don’t want no short people

Don’t want no short people

Don’t want no short people

‘Round here

Short people are just the same

As you and I

(A fool such as I)

All men are brothers

Until the day they die

(It’s a wonderful world)

Short people got nobody

Short people got nobody

Short people got nobody

To love

They got little baby legs

And they stand so slow

You got to pick 'em up

Just to say hello

They got little cars

That go beep beep beep

They got little cars

They got little voices

That go peep peep peep

They got grubby little fingers

And dirty little minds

They’re gonna get you every time

Well, I don’t want no short people

Don’t want no short people

Don’t want no short people

‘Round here

By then I was at The Village Voice, where I published a piece about this kerfuffle that in retrospect seems more abstruse and ironic than it needed to be, which is why I chose to look back instead at the more anodyne Newsday appreciation. But the Voice piece was keyed to a spinoff of “Short People” I’d written that I’ve always been proud of. I feel it merits republishing on this day of days when the vile and oft stupid (no no no, not you Mr. Musk, I just mean those swear-to-God “promise keeper” types sir) are inheriting our republic for what we can only hope is the constitutionally specified four years (or how about even less if bird flu hits the Supreme Court or something). The name of my ditty is “Smart People” and it goes like this:

Smart people got no reason

Smart people got no reason

Smart people got no reason

To live

They got great big foreheads

And ugly old clothes

They use great big words

That nobody knows

They’re plottin’ and schemin’

All of the time

Invented contact lenses

So you can’t tell they’re blind

Well I don’t want no smart people

Don’t want no smart people

Don’t want no smart people

‘Round here

Smart people are just the same as you or me

(Ave Marie)

All folks are equal

Eternally

(A Change Is Gonna Come)

Smart people got nobody

Smart people got nobody

Smart people got nobody

To love

They got tight little pussies

And scrawny little dicks

They got kinky little sex lives

That are sick sick sick

They laugh at you

And not at their self

‘Cause they think they’re better

Than everybody else

They got too much brain

And not enough soul

Some day we’re gonna bury them

In a big stupid hole

Well I don’t want no Smart People

Don’t want no Smart People

Don’t want no Smart People

‘Round here

Randy Newman’s jeans were faded, but not to that sea-and-ski-bleached shade that goes for the price of new at hip boutiques, and their only decoration was a semi-attached iron-on patch. He was lying on the floor of his hotel room, his feet on a rented electronic piano. He didn’t want to talk music, he just wanted to watch the World Series. But by the second inning some combination of politeness and obsessiveness had set him off. He just wasn’t getting that nice high from club gigs any more, and although he didn’t remember whose idea augmenting his piano with a full orchestra had been, it was logical. He just wished it wasn’t so much work.

Eventually, Newman went back to Blue Moon Odom, although for a seventh-inning stretch he suddenly remarked to his wife, Roswitha: “You know, I just don’t know how it's gonna come off Friday.” Enter Lenny Waronker, Newman’s boyhood friend and record producer, who worried him with more questions about the day’s rehearsal for the Friday contest, then brightened the room by mentioning Sports Illustrated. Mike Reid, a lineman with the Cincinnati Bengals, had told the magazine that Newman was a favorite of his. Newman already knew about it. He considered it the most exciting press mention he’d ever received.

That’s going some. If reviews sold records, Newman would be up there with Elvis Presley and The Sound of Music. No one puts him down, and his admirers compare him to Bob Dylan, Cole Porter, George Gershwin. He gets comparable respect from his peers. Harry Nilsson recorded a whole album of his songs, and Paul Simon has said that Newman’s Sail Away was the first LP in years to rouse his competitive spirit. Dylan himself went back to pay his respects at the Bitter End. What more could an artist ask?

The answer is record sales, preferably to football fans in Cincinnati. Newman has always been an original, but he has also worked within popular forms. It would seem, however, that he is more interested in form than in popularity. Newman is a pro at 28, he has been writing songs for money since his teens, whose commitment to the principle of minimal means is equally reminiscent of Sherwood Anderson and Metric Music, the schlock publisher which held his first contract. His songs have been hits for other artists. Three Dog Night went to No. 1 with “Mama Told Me Not to Come” and his cult is big enough to support a moderately lucrative performing career. But he is definitely not commercial.

As a rule, American songwriting is banal, prolix and virtually solipsistic when it wants to be honest, merely banal when it doesn’t. Newman is always concise, and his cliches are his own. He reveals his vision rather than confessing it, speaking through recognizable American grotesques to comment on some basic theme, including the generation gap (he likes neither side), God and man (he likes neither side), male and female (he identities with the males, most of whom are losers and weirdos), racism (he’s against it, but not without understanding its appeal), and alienation (he’s for it).

The strength of Newman’s lyrics is the way they create ironic tension between his own self-evident sophistication and the naivete of his personas. His music also traffics in irony, counterposing his indolent drawl—the voice of a Jewish kid from Los Angeles who grew up on Fats Domino—to the most fluent array of instrumental settings in popular music. He can rock, or sing off a bottleneck guitar, but just as often he will write in a ‘20s jazz allusion or some classical-cum-movie scoring that combines his own musical training at UCLA with his heritage as the nephew of three Hollywood composers, two of them Oscar-winners. Because his lyrics are devoid of the usual metaphorical pretensions (sample clinchers: “Till we pass away”; “Isn’t he, isn’t he round?”; “I said, you know what my name is”) and because his music recalls cliches rather than repeating them, he gets away with calculated effects that would (and do) destroy meaning-mongers like David Ackles and Tom Rapp.

Performed by Judy Collins or Ella Fitzgerald, Newman’s songs lilt. Rearranged by Three Dog Night or Manfred Mann, they drive on. The basic material is always there. But Newman doesn’t exploit it. As most listeners understand the concept, his voice isn’t so much musical as it is expressive. Although it has gained remarkable flexibility over a recording career that began five years ago, it is the kind of instrument that must be framed just so to break through to the mass audience. Newman has nothing against hit singles, and if he could figure out a way to do some of his songs justice as a hit single, he’d do the framing. He just hasn’t figured out a way.

It might help Newman to play the martyred artist, but he has no taste for the role. He’s been through what scenes he’s been through, and his only surviving habits are sloth and domesticity. It was a combination of these, plus stage fright, that kept him from touring long after his star-spangled press notices had earned him a tiny but devoted following. Once he discovered how easy it was, however, he got hooked. Replete with mordant references to the supposed banality of his chord structures and piano style, Newman’s one-man shows exacerbated the weird humor of his songs, and were good for a live album which is probably his most popular.

But even though he refuses to play the artist, he remains one of the few creators in popular music to act like one. Commercially, his next move is to form a group, but that runs counter to his fondest prejudices. Hence the 50-piece orchestra that accompanied him Oct. 20 at Philharmonic Hall. Wearing even more unassuming jeans, Newman came out in front of the tuxedos and performed many of his most profound songs as they’d been recorded, with new dimensions of richness and delicacy provided by the live sound. The result wasn’t overwhelming, just effective. By underscoring the compassionate seriousness that goes with his irony, it broke down the sarcasm that probably attracts some of his more faddish fans. And it gained him more respect from everyone who respects him totally anyway.

Newman would really like to be popular. He’d really like to reach the American heartland—nothing makes him happier than a hip audience in Iowa or Illinois or Carlisle, Penn. But in the meantime, all he can do is follow his nose. He can’t write when he tours, but he can make money, and it will probably be a long time before he comes up with enough new songs for a new album. Songs are very hard work. Maybe this time he’ll find one that he can aim right for the heart.

Re Mike Reid: also wrote a No. 1 song for Ronnie Milsap "Stranger in My House." A music grad from Penn State, Reid retired from football after a few years in the NFL, got out in part for fear of hurting his hands.

I really enjoyed reading this column -- I was a child just learning to read when it was first published. What an amazing songwriter, but also a very interesting person.