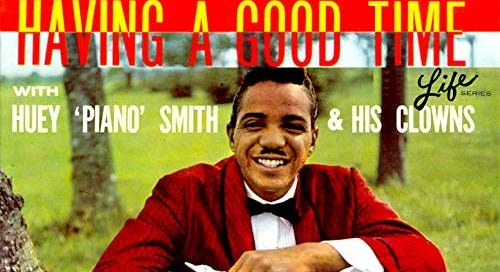

New York Times please note that it’s less of a surprise than it should be that the peaceful February 13 death of 89-year-old New Orleans piano master Huey Smith has inspired so little notice. No doubt other appreciations will eventually be added to Daniel Kreps’s timely Rolling Stone job. But there’s also no doubt that none will equal that of John Wirt in New Orleans’s own Advocate, because Wirt’s 2014 Huey “Piano” Smith and the Rocking Pneumonia Blues is and will remain the definitive biography. Without it I wouldn’t and couldn't have written the previously unpublished essay it seemed the right moment to make a Big Lookback at And It Don’t Stop. “Infectious Clowning: Huey Smith’s Rollicking Heyday and Long Sad Struggle to Get Paid” went public at the 2015 EMP Pop Conference in Seattle and shared time with the Coasters (also the subject of an EMP lecture, this one collected in Is It Still Good to Ya?) in a week titled “Playing It for Laughs” in the ‘50s course I taught at NYU in 2017. Writing the lecture inspired me to assemble a playlist that squeezes 30 singles into something under 75 minutes, including a few tracks credited to other artists although Smith plays on them. My title: That Bad Man, That Johnny Vincent, bizzer Vincent being the principal but not only reason Huey Smith never got paid like he should have.

Jeff Hannusch begins I Hear You Knockin’: The Sound of New Orleans Rhythm and Blues with a five-chapter section called “The Piano Players.” This makes sense—if New Orleans jazz is more the realm of trumpeters Buddy Bolden and Louis Armstrong than of the self-promoting piano maestro Jelly Roll Morton, New Orleans r&b is the realm not of trumpet-playing a&r ace Dave Bartholomew but of two piano men, the prolific ‘50s vocalist-songwriter-hitmaker Fats Domino and the magical ‘60s-’70s producer-songwriter-hitmaker Allen Toussaint. But purportedly in deference to a John Broven Domino book that never appeared, Hannusch doesn’t schematize it that way. The five pianists who get chapters are his source Tuts Washington, 1907-1984; Roy Byrd d/b/a Professor Longhair, 1918-1980; James Booker, 1939-1983; Toussaint, born 1938 and now 77; and my honoree Huey Smith, born 1934 and now 81. Folded into Hannusch’s Bartholomew chapter is Domino, born 1928 and now 87, who had more top 40 hits than any rock and roller except Elvis Presley. Barely mentioned is Mac Rebennack a/k/a Dr. John, born 1940 and now 74, perhaps because he only became Crescent City Grand Curator after he kicked heroin in the ‘90s.

New Orleans piano owes downtown Creole social climbing and Storyville bordello fonk. But although both factors pop up in the Jelly Roll Morton story, there’s no Creole in Hannusch’s pantheon post-Tuts Washington, and by the 1940s bordellos had given way to an uptown club circuit epitomized by a thriving joint called the Dew Drop Inn, owned by an Italian barber turned grocer turned restaurateur named Frank Painia. And the younger r&b piano maestros tended rough and weird. Rebennack’s father was a hard-struggling lower-middle class retailer. But Longhair grew up fatherless and supported himself playing cards, Booker was a gay one-eyed junkie raised by an aunt, and Domino was a very poor kid so shy he quit school at 11 to work jobs like iceman’s helper and stable boy. From a solider and more artistic precinct of the working class, Toussaint groomed himself as the 180-degree opposite: a well-tailored Army veteran in Jesus Birkenstocks who radiated humility while milking a million-dollar catalogue, drinking fine brandy, and, as Etta James once reported, paying a multitasking woman to cook his food and clean his toes. Up against these larger-than-life figures, Huey Smith seems rather ordinary.

This is where I insert my without-whom. Last summer Louisiana State University Press mailed me a biography by John Wirt of The New Orleans Advocate: Huey “Piano” Smith and the Rockin’ Pneumonia Blues. As a fan of Smith’s unforgettable title and the song that went with it, as who isn’t, I opened it up figuring I wouldn’t finish because the second half obsessed on the royalties Smith got chiseled out of. But while I put the book down several times, I never put it away. Like most biographers, Wirt overrates his subject. But like most critics, I’d underrated him. So with Wirt’s help I want to rectify that.

Smith had a fulltime father, a laborer more easygoing than his laundress mother. He grew up poorer than Rebennack or Toussaint but better off than Longhair or Domino in a household that was neither religious nor especially musical but did include a piano. So he taught himself from what he heard in the air, spending the coins his father gave him for classical lessons on movie tickets. Practicing constantly, he kept figuring stuff out, with Longhair a key local influence although Smith’s sound was less raucous. At 16 he formed an alliance with showstopping wild man Guitar Slim that quickly became a career and started drinking to overcome his natural diffidence on stage. Take that nickname literally: Huey “Piano” Smith. Master drummer Earl Palmer called him “the personification of New Orleans piano players.” Premier guitarist Earl King heard lots of non-Nawlins in the trick bag of the man he nominated “the top R&B pianist in New Orleans”: Albert Ammons, Amos Milburn, Willie Littlefield, Nat King Cole, more. Dr. John says Smith “always felt obliged to add a particular stamp to another artist’s record . . . that would make it unmistakably the artist’s own.”

As the nickname tells us, Smith was an instrumentalist first and a vocalist only when necessary. Yet in 1956 he was signed to Ace Records by Johnny Vincent né Imbragulio. A Mississippi-born a&r hustler for Art Rupe’s L.A.-based Specialty Records, a gospel label that would storm the r&b market with New Orleans native Lloyd Price in 1953 and the rock and roll market with New Orleans beneficiary Little Richard in 1956, Vincent hung out where most of New Orleans r&b hung out: Cosimo Matassa’s tiny J&M Studios. Vincent’s artists all report that he couldn’t keep a beat or carry a tune. But he always had big dreams, and so he started Ace back home in Jackson, Mississippi, 165 miles away. Right off Smith recorded a hit called “We Like Mambo,” Latin-flavored a la Longhair, with a lead vocal by bassist Roland Cook and what Smith called “everybody who could open his mouth” joining in. It appeared as a B side credited to journeyman Eddie Bo, who Vincent thought would sell better because he’d just had a hit. Instead Smith had the hit and nobody knew it. So he recorded again, two sides this time, “Little Liza Jane” backed with “Everybody’s Whalin’,” only Smith thought the B was called “Blow Everybody Blow.” Vincent renamed it because he thought ‘Everybody’s Whalin’”—a New Orleansism spelled “whale” like the aquatic mammal rather than “wail” like “weeping and wailing” that fails to surface in the song—would sell better. You’d think Huey Smith would have hated Johnny Vincent, and sometimes he did, but it was never that simple. Vincent was a rogue, a fantasist, and a fool, but the two men never lost their emotional bond. Dave Bartholomew once said: “Huey was such a nice man he was actually a friend of Johnny Vincent.” And Vincent was such a con man he got Huey Smith’s best music out of him.

In early ‘57 came the song with the title: “The Rockin’ Pneumonia and the Boogie Woogie Flu,” concocted of a phrase from “Roll Over Beethoven”—“rockin’ pneumonia”—a misprision from “Old Man River”—“young man rhythm”—and some gay bar talk—“I wanna holler but the joint’s too small”—plus, somewhere in there, a dirty joke and a snatch or two of street singsong, and, most importantly, the treble piano riff that kicks it off and then hooks it seven times. The band is aces: Earl King on guitar, Earl Palmer inheritor Charles Hungry Williams on drums, Lee Allen and Red Tyler on saxophones. Smith sings some, but the main everybody who opens his mouth is the uninhibited 18-year-old John Scarface Williams, so-called because he bore the long mark of a childhood automobile accident that almost killed him, and I don’t know who provides the “well all right” hook midsong—maybe another singer named Sidney Rayfield. At 2:17 or so, it's a classic, so jovial and loose-limbed it conjures a lowdown bar you peek into in a rainstorm and everybody says come on in. All the many cover homages are longer: Flamin’ Groovies, Grateful Dead, K.C. and the Sunshine Band, Patti LaBelle, Aerosmith, Edgar Winter, Phoebe Snow, Jeannie C. Riley, Jerry Lee Lewis, Billy Vera, P.J. Proby, Booker and Longhair and Dr. John, and most prominently Baton Rouge’s own Johnny Rivers nee Ramistella, who went number six with it in 1972. In early 1957, the perfect time for an irresistibly good-humored evocation and embodiment of the infectious new music Smith didn’t think should be called rock and roll, the original went to two r&b and 52 pop. And when it caught on, Huey Smith created the Clowns just like he’d once hitched his star to Guitar Slim’s.

Smith was on the road with Shirley and Lee, but once Toussaint quit high school and came up to replace him, he took the train back to New Orleans and assembled a touring troupe. He’d written a funny song and clearly felt, as Jason Berry et al put it in the most microwavable of all New Orleans music metaphors, “humor was the first spice in the gumbo of Deep South rock.” His direct inspiration was Billy Ward’s Dominoes, where Ward was never the star, but he also covered and emulated the Coasters, a/k/a the Clown Princes of Rock and Roll. He recruited Williams, Scarface not Hungry; Sidney Rayfield, soon replaced by laugh-a-minute female soul principle Gerri Hall; and Roosevelt Wright, a teenaged bass man he picked out of the Clowns’ very first audience who was still with him in 1978. Backing musicians at one point included both Robert Parker of “Barefootin’” fame on sax and Jessie Hill of “Ooh Poo Pah Doo” fame on drums. And for a serious spell the Clowns’ driver was Rudy Ray Moore, later to make a name for himself as the blue comedian Dolemite.

But the most important Clown—literally Mr. TCB as things progressed—was once and future drag queen Bobby Marchan. Smith was essential on piano—when he got touchy about touring, as began to happen all too soon, only the virtuosic James Booker could replace him. And it was Smith who had the wit and wisdom to name his group the Clowns and make sure that’s what they were. But Marchan was the lead singer on stage and often on record, so far up front and so ready to let audiences believe the singer was the guy with his name on the act that Huey’s mother had to fend off rumors that her son was “a big fat sissy.” It was Marchan who drove the Clowns to upstage every other act on the bill, who choreographed routines off their nonstop offstage fooling around, who put everybody but Roosevelt Wright in wigs and drag, who had them open for big-voiced balladeer Roy Hamilton in tuxedos with the pants cut down to Bermuda shorts.

The point of the Clowns’ clowning wasn’t transgressive. It was to say this isn’t weird it’s a party, to say we’re all chickie wah-wah, to say “He’s a big fat sissy and so what.” But few American cities have been more gay-friendly than what I will just this once call the Big Easy, and in point of fact, Huey Smith and the Clowns were a lot more relaxed about homosexuality both onstage and offstage than Little Richard, and not just because Little Richard never relaxed about anything. How far they could take their tolerance in the late ‘50s, however, was of course severely limited—not a whole lot further than the unisex party in Jailhouse Rock. And to whom they took it was also limited.

Like most ‘50s label massas only worse, Eddie Vincent would give you a car in lieu of paying you royalties, though once he also came up with a $4000 down payment on a house that Smith told Wirt was “the highest money I ever got from Johnny in my life.” The car was a station wagon dubbed the Rocking Pneumonia in which the musicians rode followed by a Clown car when they weren’t all on some Irvin Feld megatour. The Clowns played a lot of colleges, invariably white ones, although they did also hit the Apollo-Howard circuit as well as local venues, so assume Smith was exaggerating when he told John Wirt “we didn’t know nothing about playing for blacks.” But he definitely didn’t like touring. Possible reasons, which Wirt doesn’t explore, are the shyness that had him hitting the bottle before hitting the stage, the exacerbation of a childhood hearing problem as he stationed himself near the drums, back pain that started with a Florida car crash, the family life touring is hell on, and the fact that as “the top R&B pianist in New Orleans” he had a ready source of income back home. And then there was his distaste for the whole idea of rock and roll.

On the one hand the Coasters were where the money was and Huey Smith was shrewd and pecuniary enough to follow their lead. On the other hand, well, here is Wirt: “Huey first saw the term ‘rock ‘n’ roll’ in a 1954 issue of Jet magazine. He didn’t like it. ‘Well, how they get to naming it?’ he asked. To begin with, musicians in his circle moved indiscriminately between blues, rhythm-and-blues, and jazz. ‘We all that all the time, not that you go’ call this “this” and that “that.” It’s music.’” Wirt sympathizes; I don’t, both because the kind of critical distinctions musicians resent are my lifework and because I think ‘50s rock and roll, catchall concept though it was and limited progress though it represented, was a good thing both artistically and sociopolitically. I also think Huey Smith’s recorded achievement proves it.

Smith’s biggest hit wasn’t “Rockin’ Pneumonia.” It was an early 1958 ensemble-sung goof constructed around the Rudy Ray Moore catchphrase “Don’t you just know it,” the catchiest of many anything-goes shuffle grooves he oversaw before and after, including the “We Like Mambo” remake “We Like Birdland”" the racially multivalent “Well I’ll Be John Brown,” the sexually symptomatic “High Blood Pressure,” the timely “Beatnik Blues,” and my favorite, the tequila-soaked Bobby Marchan showpiece “Would You Believe It (I Have a Cold)” (“And I’ve never felt better in my life”). “Ooh Poo Pah Doo” and Toussaint’s 1975 Wild Tchoupitoulas album remain the pinnacles of this concept. Lee Dorsey remained miraculously amiable long past his sell-by date. But over some three dozen tracks in half a dozen careening years, the good-natured geniality of Smith’s chops and groove generated a merriment in which collectivity was of the essence. His virtuosity and his willingness to fit in were both so principled he had a right to resent pigeonholes. But he was as great a rock and roller as Fats Domino or Bo Diddley if not quite Chuck Berry.

“Don’t You Just Know It” went number nine pop that spring. And Smith’s first last straw with Johnny Vincent came that fall, when he penned and cut a follow-up on which Vincent erased John Williams’s vocal and subbed in an 18-year-old Italian-American doing business as Frankie Ford. In the dawning teen-idol era, would Scarface’s “Sea Cruise” have done as much business as the handsome young white kid’s, which topped out at 14? Probably not. But it would have been a hit, and hence a lifeline. So Smith up and switched to Imperial, where the waning mainstay Fats Domino had close to 20 top 40 hits yet in store. Smith had zero—because in 1962, when he tweaked a New Orleans dance craze called the popeye on a single destined to rise up the pop chart, Johnny Vincent stole the record from Imperial and Smith found himself back on Ace.

And that was pretty much that. A few of the 30 tracks on the mix CD I’ve burned myself are post-1959, a few non-Vincent. But not many. I heard enough good things about 1962’s ‘Twas the Night Before Christmas to download it unheard, only to encounter enough half-assed music thereon to send it back up the chimney. I bought Charly’s 1966-1978 Banashak and Sansu double CD with only “It Do Me Good” and “Coo-Coo Over You” to show for it—Wirt reports that the Sansu stuff was demos cut quick with an unrehearsed funky white band and mixed and released sans contract, never Stateside. Seems like Minit et al’s Joe Banashak was a pretty good guy and a pretty bad businessman and Sansu’s Allen Toussaint was a well-fixed genius who left the dirty work to his enabler Marshall Sehorn.

But Huey Smith collaborated in all this mediocrity. Shrewdly but not shrewdly enough, he assessed the market and concluded that rock and roll jollity was out and conscious soul was in, and that this left him nowhere. Toussaint could handle the transition from Jessie Hill through Irma Thomas and the Meters and “Lady Marmalade.” But though by most accounts Smith could play as much piano as Toussaint, he lacked the flexibility and confidence to negotiate post-‘50s post-r&b. He slowed the tempos, strained for jokes, patched in emotive for comedic, fretted where he once hung loose. The records aren’t bad. They just aren’t inspired. In the ‘50s inspiration was his state of being.

Huey Smith isn’t the only rock and roll adept who had trouble getting out of the ‘50s. It wasn’t easy for anyone. But at least Chuck Berry, Little Richard, and Fats Domino oversaw myths so large they could spend the rest of their careers touring and collecting some portion of their proper royalties. It was harder for the Coasters, who had no publishing and split into rival factions. And it was much harder than that just structurally for Huey Smith, who hated touring, whose hits were fewer and smaller, and whose royalties went to Johnny Vincent and then, after Vincent elected to register all of Smith’s bestselling songs with the U.S. copyright office in 1967, to Johnny Vincent's father-in-law. Nor did the dreaded Beatles make anything easier for veteran r&b acts, in New Orleans or anywhere else, although the many r&b loyalists who have bemoaned this development never seem to recognize that rapid change is pop music’s way.

So by the late ‘60s Smith was augmenting his shrinking musical income by working as a funeral home driver and starting a gardening business. Simultaneously, he got religion—like his originally irreligious mother, he became and remains a devout Jehovah’s Witness. His second wife is also a Witness, and also a featured singer on his Sansu recordings. There’s no sign his faith made him intolerant—he remains remarkably understanding about human peculiarities, even Johnny Vincent’s. But it certainly didn’t loosen him up. He long ago moved from New Orleans to Baton Rouge. Nor has his epic struggle for his royalties—an unusually stubborn and not always practical one, because shy Huey Smith is a very proud man, but also an engrossing study in music-biz screw-the-artist procedure through all its tangled ramifications—whetted his appetite for a return to the studio or the boards.

But that station wagon left the garage fifty years ago. How long Huey Smith could have kept on clowning if Johnny Vincent had let him keep “Sea Cruise” is a guess, but say three-four years tops—till the Beatles sounds right, or maybe just Motown. He was “the top R&B pianist in New Orleans” only till Allen Toussaint went into gear in 1960, and unlike the more virtuosic Booker or the more memorable Longhair, he never had a soloist’s or a showman’s gift. Instead, he was a born collaborator who’s the auteur of a substantial body of work that’s just plain fun in more ways than we can count, because that’s the way that precious thing just plain fun is. He couldn’t have done it without his troupe. But there’s no sign he could have done it without his exploiter Johnny Vincent either—it’s almost like Vincent’s hang-loose m.o. leached into the music. I could tell you a story about their 1980 meeting, but instead another injustice will have to wrap this up.

I just taught Huey Smith at NYU Tuesday, and to prep the class created a Spotify playlist as I always do. There I found four—that’s right, four—Ace-period Huey Smith recordings: “Rockin’ Pneumonia,” “Don’t You Just Know It,” “High Blood Pressure,” and “Beatnik Blues.” Celestial jukebox my patootie. This is the music I want in my blue heaven. [Author’s note: When I wrote this lecture in 2015, Spotify was scandalously short on prime Huey Smith. This caesura seems to have been rectified well before he died.]