The Big Lookback: Ghost Dance

The struggle to make sense of how things felt — and sounded — 20 years ago

The 9/11 bombings fucked me up, as they did every New Yorker I know. On that date I was still posting to the National Arts Journalism Program’s ARTicles blog, where on September 8 I put up an appreciation of musicologist Christopher Small. There wouldn’t be another post till November 26, and it wasn’t just me—soon ARTicles itself bit the dust. But of course I still had a job at The Village Voice, an emotionally sustaining one at that, and by October I was staying alive by clubbing at a furious clip abetted by the rescheduled CMJ Music Marathon: among many others Cachaito Lopez, the Ass Ponys, Joe Strummer, Burnt Sugar, Clinic with their eerie face-mask shtick, several times the Moldy Peaches who I’d spent September 10 with, and the Coup, whose excellent Party Music came out late because they they felt moved to change a no longer metaphorical cover that depicted Boots Riley and Pam the Funkstress blowing up, true story, the World Trade Center.

I began my 9/11 at around 8:45 by walking over to 11th Street, where I was surprised to see a rubber-coated firefighter emerging from a tenement, to move my car to 12th. Then I got on my bike to deliver something to my daughter’s pediatrician on Broadway north of Canal. There I learned from a pool of people on the sidewalk that not one but two planes had struck not one but two WTC towers. In the minute or two I stood there stunned before racing uptown, I flashed first on Al Qaeda, who I knew had bombed the U.S.S. Cole a year before, then Iraq, which I knew the Cheney-Rumsfeld-Bush troika would do everything they could to blame. It took Carola and me hours to determine that students couldn’t leave Nina’s Long Island City high school without a guardian, whereupon I peddled uptown with every quarter in the house in my pocket—we’d never bothered to get a cellphone. On the crammed Queensborough Bridge younger pedestrians helped me hoist my bike from walkway to roadway. Nina was one of the last students to be fetched from her school. We watched TV in the Piccarellas’ house in Astoria until no one could stand it anymore and took the 7 train home when the subways went back up that evening.

While I was being a dad, Voice editor Don Forst had literally stopped the presses so that theater critic Alisa Solomon, who’d not only witnessed the south tower get hit as she emerged from the Chambers Street subway but had the presence of mind to get contact info from a nearby photographer, could get her saga into the issue that had already been put to bed. But next day I was back at work, where I made myself useful by biking over to a firehouse on 2nd Street to research what we weren’t yet declaring an obit about punk rocker Johnny Heff of the Bullys, who worked as a firefighter like my own dad—presumably the very guy I’d glimpsed on 11th Street the morning before. It included a punk-flavored screed from from the band’s website that began: “The government of Afghanistan, is waging a war against women. Where the fuck is Afghanistan? I gotta get a fricken map for that one. Anyway, it must be one tuff motherfucker to wage a war against chicks, huh?”

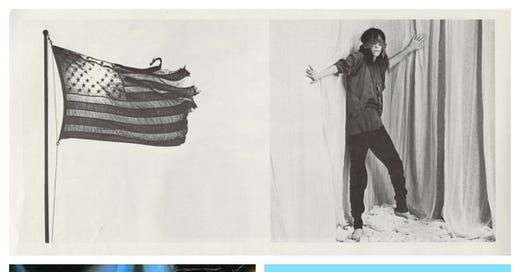

But that tiny contribution to the Voice’s coverage was just delaying the inevitable—the column I had due for the issue that would go to bed September 18. I had no idea what I could say until the Web radio show the Voice had me doing provided a frame for the labor of pain that is this month’s Big Lookback, “Ghost Dance.” Wondering how that music would sound now, I playlisted the songs it mentions. Except for the quickly deleted “Rock and Roll Nigger,” which sounded even worse than I’d feared and which I doubt I included in my show, it still proved tremendously evocative. Muslim-Christian Ivoirian-Rastafarian Alpha Blondy, antiwar noise-bomber Lemmy Kilmister, leftwing punks the Clash, leftwing Christian Bruce Cockburn, Sufi healer Orüj Güvenç, and uxorious atheist John Lennon still contextualize the unhinged, accidentally apposite transformation of waste that is Patti Smith’s Easter.

“Ghost Dance” is the keystone of a section of my Is It Still Good to Ya? collection called “Millennium,” which leads with “Music From a Desert Storm,” originally “A Little War Music,” a thoroughly researched 1991 piece about the music of what was tragically and disastrously only the first Iraq war. The section also includes essays on the Moldy Peaches, Steve Earle, Youssou N’Dour, and M.I.A. It’s followed by an African section that ends in Mali with a piece I retitled “Music From a Desert War.” At the 2001 CMJ, which was supposed to begin September 12 but got put off a month, I chaired a 9/11 panel that included Danny Goldberg, Joe Levy, Tom Calderone of MTV, Iraqi-American journalist Lorraine Ali, Israeli-born techno artist Raz Mesinai, and Iraqi-Cuban bizzer Fabian Alsultany. My opening remarks, during which I teared up, were considerably less impressionistic than “Ghost Dance,” as was the CMJ column I later published in the Voice.

Wednesday there was e-mail from Jessica Hopper of Hyper PR in Chicago, apologizing for having to tell us where her bands were headed now that CMJ had been postponed. “Nothing like profound tragedy to make our myopic punk rock world and scene squabbles seem truly meaningless,” she began, struggling like everyone else for language that would grab and hold. “We’re planning to donate the cost of our unused seats out to CMJ to the Red Cross and various rescue funds. It’s hard to know what to do, a feeling I’m sure everyone can identify with.” Perhaps it was because I’d learned from Charles Cross’s Heavier Than Heaven that Hopper was staying in Kurt Cobain’s house the morning Cobain shot himself (undetected, in a separate building) that I found her use of the exhausted, inescapable “tragedy” so much more striking than that of, say, Justin Timberlake, who seemed every bit as honorable and distraught. I mean, this woman had some expertise—Cobain’s death was a profound tragedy too. But the difference in scale is qualitative. Rock and roll overcame tragedy in Cobain’s music as surely as tragedy overcame rock and roll in his life. This time, it’s tragedy in a clean sweep.

Talk blues till you’re blue in the face, cite all the music we love that has a darkness to it, and rock and roll still remains a uniquely American reproach and alternative to what a European existentialist long ago dubbed the tragic sense of life. Invented by and for teenagers in a time of runaway plenty, it’s not blues by a longshot, and from Chuck Berry to the Beatles to the Ramones to Madonna to OutKast a fair share of its masters have made extinguishing darkness their lifework. They come in knowing that love hurts and everybody dies, but they have the inner confidence to remember there’s more to life, and to prove it. The music’s confidence—in addition to its deeply democratic form, its African slant on melody and rhythm, and its Cadillacs with cherries on top—was why rock and roll took over a Europe that was only a decade past World War II. We were too, of course. But our mainland hadn’t been attacked by a hostile power since 1814. War had never endangered our lives, ravaged our world, happened in front of our eyes. Now, as we count our dead, adjust our expectations, replay those crumbling towers in our minds, and prepare for horrors to come, it has. Tragic-sense-of-lifers like to grant the Bomb a crucial role in rock and roll consciousness. I’ve always suspected that was liberal rhetoric, that at most ‘50s nuclear fantasies added edge and flavor. Now I’m sure of it. Our inner confidence, if it’s there at all anymore, will never sound the same. If I live long enough, I’ll finally have something to get nostalgic about.

Of course, what made the confidence doubly winning was its commonness—its commitment to music/language at its most vernacular. That’s why the worst flatline of our president’s Oval Office chat the night of the attack came when he avoided the King James version of the 23rd Psalm for one of the Business Writing 1 translations that palliate well-heeled fundamentalism all over suburbia. “The folks who did this” was mind-boggling enough. But how could even George W. have imagined that “You are with me” would get anyone’s heart beating like “Thou art with me”? Just when we needed a jolt of moral certitude, the glad-handing frat boy grayed out like the policy wonk we wish he was. We vernacular fans can see the connection between “the folks who did this” and the hard-wired rootsiness that afflicts a gamut of fools from Pete Seeger to Lee Greenwood, just as we can connect “You are with me” to L.A./Stockholm megapop. And I hope we sense that in this time of unprecedented trouble the long-impacted grandeur of “Thou art with me” is the kind of vernacular we need. As a Bible-believing Christian turned convinced atheist, I never miss a chance to shout that rock and roll is secular music. But that hardly means it doesn’t have religious sources or express religious feelings. I know, religious feelings got us into this hell. And I can now guarantee that there are atheists in the valley of the shadow of death. I doubt there was anyone without religious feelings last week. Death is every atheist’s window on the eternal.

I hadn’t yet pinned this down Tuesday when I finished retrieving my daughter from school in Queens. But I already knew I wanted to begin my next show on the Voice’s fledgling Web radio station with the atheist’s hymn: from “God is a concept by which we measure our pain” to “I don’t believe in . . . ,” John Lennon’s “God” summed up a mood, and for Carola and me that was reality. Soon I figured out where I’d end, too: with Sufi shaikh and Istanbul medical professor Orüj Güvenç chanting “Bismillah ar-Rahman,” one of the names of God. But though devising a playlist was the only way I could think of to pretend I had a use in the world without confronting my own inanity, finding the right songs was a lot harder than it was during the attack’s geopolitical cause and CNN forerunner, the Gulf War. “What’s Going On” seemed way corny, and “From a Distance,” unfortunately, was no longer an apposite metaphor. This was a time for some of the rage music that I love as art and rarely need in life. Punk for sure, “Hate and War,” but before I even got there I was on the only metal band I care for deep down, Motorhead.

“Bomber” is a classic piece of hard rock power-mongering, identifying with the thing it loves and hates: “Scream a thousand miles/Feel the black death rising moan/Firestorm coming closer/Napalm to the bone/Because you know we do it right/A mission every night/It’s a bomber/It’s a bomber/It’s a bomber.” But it doesn’t vaunt itself the way metal usually does—it’s too fast, too crude, too prole. And though the poorly read might get the impression Lemmy thinks napalm is cool because he too attacks every night, he doesn’t—the only reason Motorhead fans don’t know he’s written as many antiwar songs as Bruce Cockburn is that they’ve never heard of Bruce Cockburn. I prefer Lemmy’s because he understands better than Cockburn--whose greatest moment, to his undying credit, expands on the theme “If I Had a Rocket Launcher”—the attractions and uses of violence. The same goes for a lot of loud rock and roll, where what’s praised as sexuality is often sublimated aggression. But that didn't make my song hunt any easier, and casual listening, to escape or find solace or get some fucking work done, was a trial—most records I could hardly bear to play. Everything lacked the proper focus and gravity. Everything seemed too sure of itself.

As the trauma recedes, my ears are coming out of their shell a little. So I suspect it will take more than one unspeakable catastrophe to destroy the aesthetic I’ve made my calling, and wish I had faith there won’t be another. But for all the solace I’ve derived from other people’s nominations—Joy Division, Neil Young’s After the Gold Rush, and especially the Ramones’ class-proud Too Tough To Die, a favorite of missing firefighter Johnny Heff, known to his fans as punk rocker Johnny Bully—the record I’ve played like a teenager is one I ransacked for my show that first night. I wanted a victory song, which in rock and roll too often means a plodding march steeped in the European triumphalism metal takes from the symphonic tradition, and I also wanted a reconciliation song, a rebirth song. These cravings weren’t rational; maybe I should have known better. But I felt compelled to locate my copy of Alpha Blondy’s formerly nutty “Yitzhak Rabin.” And in some crevice of my memory, prised open perhaps by the artiste’s Rimbaud-worshippin’ penchant for desert mysticism and other Islamic BS, I zeroed in on Patti Smith. And that’s how I got to Easter.

Amazon bestseller Nostradamus has nothing on Easter. The booklet says “Till Victory” is about “the destruction of the machine gun by the electric guitar,” and I hope that’s a prophecy. Meanwhile, an anthemic melody, one that like all great Kaye-Kral-Daugherty reclaims European vainglory as Americanese vernacular, channeled my rage into “Take arms, take aim, be without shame” and “God do not seize me please, till victory.” After the Springsteen-styled hit that seems so beside the point now, “Ghost Dance,” a Plains Indian chant meant to resurrect anyone’s forefathers, segues to the minute-and-a-half spoken-word “Babelogue,” where I was amazed to hear Smith ranting “In heart I am Moslem; in heart I am-an-am-an American” before launching the fierce and no longer suspect “Rock N Roll Nigger.” And only later in the week did I register “25th Floor,” an unhinged rocker about fucking in a men’s room high above Detroit: “Oh kill me baby/Like a kamikaze/Heading for a spill/Oh but it’s all spilt milk to me.” It spills into another rant, about shit and gold and alloys and “all must not be art,” and also “the transformation of waste,” repeated like a mantra. Great song. It’s aggression changed back into sexuality, it’s “some art we must disintegrate,” it’s the music I’ll take away from the death of the World Trade Center and God knows what else. It’s a transformation of waste. It’s a dream of life. It’s a small thing that will have to do.