The Big Lookback: Drive-By Truckers

"The Righteous Path," Barnes & Noble Review, March 24, 2011

Published in 2021, Stephen Deusner’s Where the Devil Don’t Stay: Traveling the South With the Drive-By Truckers had been on the to-read shelves behind my desk chair for more than two years when I plucked it out three-four weeks ago, and I’m still 100 pages from where it ends at page 248. So right, a quick read it isn’t. Solid, thoughtful, fact-filled, and stimulating it is, however and whenever I finish it—I tend to read several books at once—I hope to give it its own review. In the meantime it’s had me wondering why the hell I didn’t squeeze this month’s Big Lookback—originally published in March 2011 under the auspices of the great Bill Tipper in Barnes & Noble Review—into my 2018 collection Is It Still Good to Ya? Miranda Lambert made the cut, Brad Paisley too. The Drive-Bys are a terrific live band who made more good albums than both of them put together—although it’s true that in concert the consistently superb lyrics by Patterson Hood and Mike Cooley tended to be muffled by the two-guitar attack. But I can attest to this. When they hit NYC again in October I’ll do what I can to catch them live even if it means reactivating my walker.

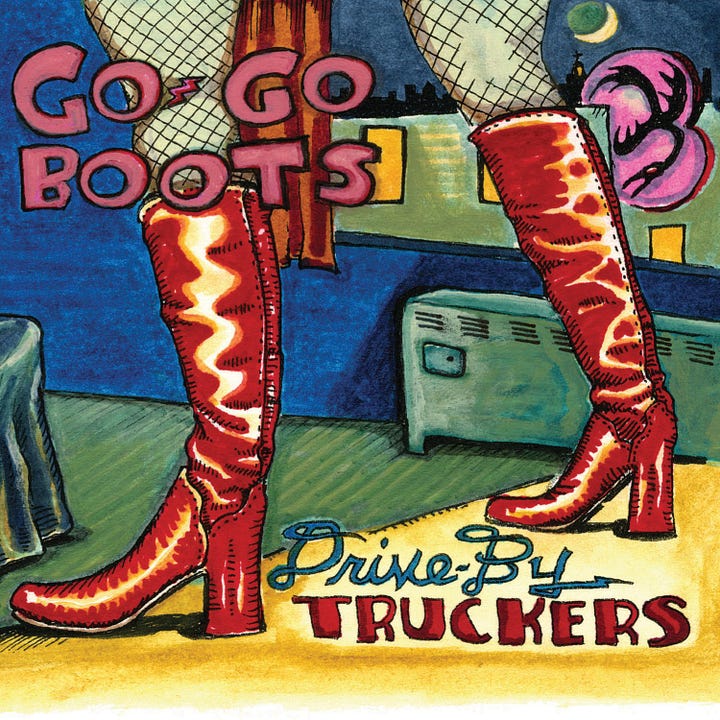

Go-Go Boots is the Drive-By Truckers’ 12th album and not their best. Before I attended its two-hour christening at the Bowery Ballroom on February 15th, I wasn’t sure it was worth a column. Nor did the show itself convert me, though I enjoyed it even more than any of the four other excellent DBT gigs I’d caught at steadily enlarging venues since 2003. Instead, it demonstrated that conversion experiences weren't the point with this band. The Drive-By Truckers don’t do transcendence. They do persistence. They do body-of-work.

Since their debut Gangstabilly in 1998, this hard-touring, Georgia-based, Alabama-spawned aggregation has been the most productive good band on the planet. The senior partners are garrulous 46-year-old Patterson Hood, who’s also thrown two solo CDs into the pot, and his much quieter and slightly younger pal, Mike Cooley. But they definitely head up a unit. Drummer Brad Morgan has been their rock since 2001, bassist Shonna Tucker joined in early 2004, and John Neff’s steel guitar was all over 1999’s Pizza Deliverance. The one major fissure involved the 2007 departure of a junior partner named Jason Isbell, around since 2001 and also for a time Tucker’s husband. Hood is a phenomenal songwriter, Cooley a terrific if less prolific one. The much younger Isbell gave them yet a third, as well as a three-guitar attack and a clean, achy near-tenor drawl that contrasted splendidly with Hood’s crinkly-to-ratchety one and Cooley’s laconic low end. He also came up with their most revealing song, “Outfit,” from the superb 2003 Decoration Day, in which a 42-year-old housepainter gives his son leave to go join a band, with provisos that include a chorus that says it all: “Have fun but stay clear of the needle/Call home on your sister’s birthday/Don’t tell them you’re bigger than Jesus/Don’t give it away.”

The Drive-By Truckers aren’t bigger than Jesus. They aren’t even bigger than Kings of Leon, or Jesus’ Son. But body-of-work-wise, they deserve to be. Between their three guitars, their region of origin, and their career-making, Lynyrd Skynyrd-inspired 2001 double-CD Southern Rock Opera, they’re slotted as Southern rock themselves. But beyond accents and generalized guitar noise they don’t sound much like the Allman Brothers, virtuosos down to their two drum kits, or Skynyrd, who boogied just as irrepressibly without playing half as good, or for that matter Kings of Leon, who, beneath their Pentecostal backstory, are a hooky pop-rock band with a drawl. The DBTs do favor the trad chords and songforms that are fast disappearing from intellectually respectable “rock.” But they’re cruder and less funky than the Southern rock of yore, down with punk, grunge, and garage—all the better to set up the articulation of the voices up front, and to add heft, breath, and entertainment value to the words those voices sing.

A dozen albums in, that’s a lot of words—almost 200 songs including the two Hood solo jobs. These are not lapidary gems in the Brill Building/Music Row manner. Hood is generally a storyteller, while Cooley favors a more formally conventional lyrical-philosophical-allusive mode. But though all quality songwriters master brevity, neither can be called terse. Tot up the lyrics in their gorgeous booklets—Virginia-based Wes Freed does all their cover art and illustrates inside too, sometimes down to individual tracks—and you’ll find many stanzas that exceed the 80-word limit pop gatekeepers impose on whole songs. Not only is this a body of work, it’s suitable for a PhD thesis, several of which I bet are in progress, because like no other Southern rock band, the Drive-By Truckers document the South. Not the whole South, granted—the white South, though they have no use for those they forthrightly label “racist.” But that’s plenty. The roughly similar Hold Steady locate most of their narratives in a world of barflies and aging rock kids. The Drive-Bys left that scene behind years ago. All strugglers are their province.

The odd album out was 2006’s A Blessing and a Curse, undertaken after the DBTs followed Southern Rock Opera and Decoration Day with 2004’s excellent if slower The Dirty South and still couldn’t pay their bills. So they set themselves to squeezing 11 songs into 43 minutes without telling a tale or mentioning a Southern place, although Cooley cheated with “Space City”—which along with the Hood sermon “A World of Hurt” outshines everything else on a project whose blessings were scant, with Isbell quitting after it was done. But that still leaves a whole load of songs about the South, and if plenty of these are about the rock life itself, that life isn’t always their own: Southern Rock Opera is about Skynyrd first and a memoiristic DBT second, and later came Carl Perkins (sad), George Jones (jocular), and the matched junkies of Canadian Dixie-roots figureheads the Band, “Danko/Manuel” (funereal). Anyway, other themes have proven just as durable.

The Drive-By Truckers have always spoken up for the underdog louder than most bands. But though they’ve shown a grasp of the purely economic since Cooley’s 1999 “Uncle Frank,” about an illiterate smallholder driven to suicide by a TVA land grab, most of their early sympathies wound up with a typical rock and roll assortment of stunt riders and substance abusers, which augmented by their colder-than-Nashville eye for connubial gloom gave them plenty of hard-ups to sing about. As Hood and Cooley found fans, however, they grew more responsible and more tender. On Decoration Day, for instance, Hood’s “My Sweet Annette,” in which Annette gets left at the altar back in 1933, and “Your Daddy Hates Me,” which doesn’t stop Hood from loving her daddy, aren’t happy songs, but they aren’t merely “dark” either, and Cooley’s “Sounds Better in the Song” sees through the musical wanderer who brags, “Lord knows, I can’t change.” The Dirty South didn’t derail this trend—“Puttin’ People on the Moon,” about cancer in a factory town gone to rust, epitomizes it. But it did indulge their more cinematic ambitions, including several songs from an abortive Hood project about organized crime. Then came the Isbell split—which all parties are polite about, although for sure Isbell is headstrong, and for sure the memorable songs on his two solo albums deserve livelier company than those other ones. And then, after a payday tour with the Black Crowes, came 2008’s transcendent Brighter Than Creation’s Dark.

Most DBT fanatics swear by Southern Rock Opera and Decoration Day, and so do I. But it was Brighter Than Creation’s Dark that made me a fanatic too. With Neff’s steel keening away, it’s their most country album, but there’s a soulfulness in it when Shonna Tucker steps to the mic, and crucial keyboard colors from legendary white-soul songwriter-sideman Spooner Oldham, who worked with Patterson’s bass-playing dad David Hood in the heyday of Muscle Shoals. Hood’s vocals are subtler, more thoughtful than vehement, and superior melodist Cooley chips in seven tunes less sardonic than a norm in which even one called “Marry Me” leaves you wondering what the catch is—like “Bob,” a fond look at the local gay guy and/or oddball, and “Lisa’s Birthday,” honoring a party girl who turns 21 several times a year. Hood’s topics include a husband’s drink, a husband’s meth, a husband’s pre-emptive suicide, a husband remembering his family from heaven, GI shoots Iraqi, GI’s wife can’t sleep, opening acts, the cinematography of John Ford, and, my favorite because nothing “happens,” the tone-establishing “The Righteous Path,” which begins “I got a brand new car that drinks a bunch of gas/I got a house in a neighborhood that’s fading fast” and heads downhill without crashing. Yet.

In an unusually meaty rock-doc shot five years ago but released on DVD simultaneously with Go Go Boots, Barr Weissman’s The Secret to a Happy Ending, Temple University historian Bryant Simon calls the Drive-Bys “a very political band. They write about class all the time.” This kind of perspective is both unheard of and the nub, because it extends the explicit class animus and secular skepticism of Cooley’s “Uncle Frank,” Hood’s “Sink Hole,” and Isbell’s “The Day John Henry Died” to the sullen desperation of the band’s domestic dramas and low-life blowouts. Brighter Than Creation’s Dark takes the opposite tack. Hood's laid-back mood, Cooley’s kind calm, and Tucker’s female principle jell around “The Righteous Path” until it feels like an album about—to take a few of Hood’s words out of context—“the good things, and that’s much, much harder.” I was disappointed to learn recently that the husband-in-heaven “Two Daughters and a Beautiful Wife” was inspired not by the premature death of a fictional dad but by the spree killing of an entire real-life family—a family Hood, who carries a trouble magnet in his jeans, knew personally. I’d much rather he write human interest stories than TV treatments.

Loving an album the way I love Brighter Than Creation’s Dark can spoil ordinary pleasures, and so I failed to fully appreciate The Big To-Do in 2010, though Lord knows I tried. Go-Go Boots I’m more objective about—solid record, no Decoration Day. Both are the good work of a great band who resemble Tom Petty’s Heartbreakers more than they used to—new pianist Jay Gonzalez is a Benmont Tench type rather than a Spooner Oldham type, which as avowed Petty fans the other guys knew coming in. But that’s a detail. There are those who prize the Drive-Bys’ music per se—they cut a Muscle Shoals album with late-breaking soul diva Bettye LaVette and won a 2010 Grammy for the instrumental Booker T. collab Potato Hole. And I like them fine as a band—at the Bowery Ballroom Cooley’s solos riveted, and when Neff picked up a Gibson they were Skynyrd enough for Neil Young himself. But their overwhelmingly male audience adores them for a songbook with few equals, and topping Brighter Than Creation’s Dark straight away was, simply put, impossible. So the next two were merely mortal, and although I wish the title song of Go-Go Boots, in which an evil preacher hires hit men to off his wife (and there’s more), was more John Ford and less The Glades, I’ll make do and then some with Shonna’s soul and Cooley’s ready-steady and the Eddie Hinton covers and the cop-vet pairing.

I don’t use my shuffle function much because I still subscribe to the belief that albums signify as such. But with this body of work I decided to stick five lesser CDs in the changer and find out what happened. Of course, songs entered my cerebellum afresh—the old “Zoloft,” pretty juvenile (as they knew); the new “The Weakest Man,” pretty pathetic (as he knew). But most of all the Drive-By Truckers’ music per se revealed itself from Pizza Deliverance, back when they were notional gangstabillies flipping the bird at the cheap all-American-ness of the New South, to Go-Go Boots, in which they surely hope reside residuals sufficient to cover their Koch-targeted healthcare costs and kids’ educations. By no means is it one seamless thing—guitars that once twanged and abraded now boom and envelop, and the unembellished beat has muscled up. But what’s most striking is how the voices provide sound as well as meaning. Like many lesser singers, Hood and Cooley resist description. Hood isn’t near pretty and switches sandpaper grades regularly, yet he’s sweet a lot and thoughtful more and more, and at times his drawl can seem as universal as a ‘60s Brit’s. Cooley is more unreconstructed, with a depth that suggests George Jones admiring Lefty Frizzell’s flow and the diffidence of a fella who’ll crack one hell of a joke 15 seconds after that stranger leaves the room.

Those are just takes, of course. With important voices there are always more. So let me leave you with Walter Cherretté, a Belgian commenter on my MSN blog, where gather many DBT fanatics, who claims he doesn't speak English well enough to register lyrics—which can’t be entirely true, but point taken. It was a blog comment in a second language, so I’ve cleaned up the grammar: “I’m always asking myself what does that voice mean. It may be the most beautiful lyric, but if that person’s voice doesn’t hit me, it means nothing to me. Never understood the lyrics to ‘Like a Rolling Stone’ or ‘Expecting to Fly.’ But they were American voices, and so’s Patterson’s."

Except to add “So’s Cooley’s,” let’s leave it there. — Barnes & Noble Review, March 24, 2011