A month or two ago I got the letter below as an Xgau Sez question, and wrote the answer that follows in response. But rather than merely link to the diary I cited, which ran over two weeks, I thought I’d publish the whole thing as a single Big Lookback. There is, however, a link to the more painstaking and essayistic “Vendant l’Afrique.”

Have you ever had the chance to travel to these African countries whose music you love so much? If so, I think I speak on behalf of everyone when I say it would be fantastic to hear a travel story or two please! — Jake, Newfoundland

I’ve managed to visit Africa twice. In 1995 I attended the second biannual Marché des Arts du Spectacle Africain in Abidjan, recounted in a Voice column called “Vendant l’Afrique” that’s collected as part of the Africa section of Is It Still Good to Ya?, and on a visit to Dakar in 2010, where I was put up by my ex-student Drew Hinshaw and his fiancée Celeste Mason. Drew, who for years now has covered much of Europe for the Wall Street Journal from Warsaw, where he lives with Celeste and their two kids, began his journalistic career as a foreign correspondent in Ghana and then Senegal; he co-authored a compassionate, dogged, skeptical, inspiring, and very much recommended 2021 book about the kidnapping of 276 Nigerian Christian high school students by Islamic militants called Bring Back Our Girls. I spent quite a memorable week in Dakar, not all of it music-focused, and was very lucky to enjoy not just the hospitality but the guidance of Celeste and especially Drew, who has a tremendous ear for languages and proved fluent in both French and Wolof. I was working for MSN at the time and there published a two-part diary recounting my adventures.

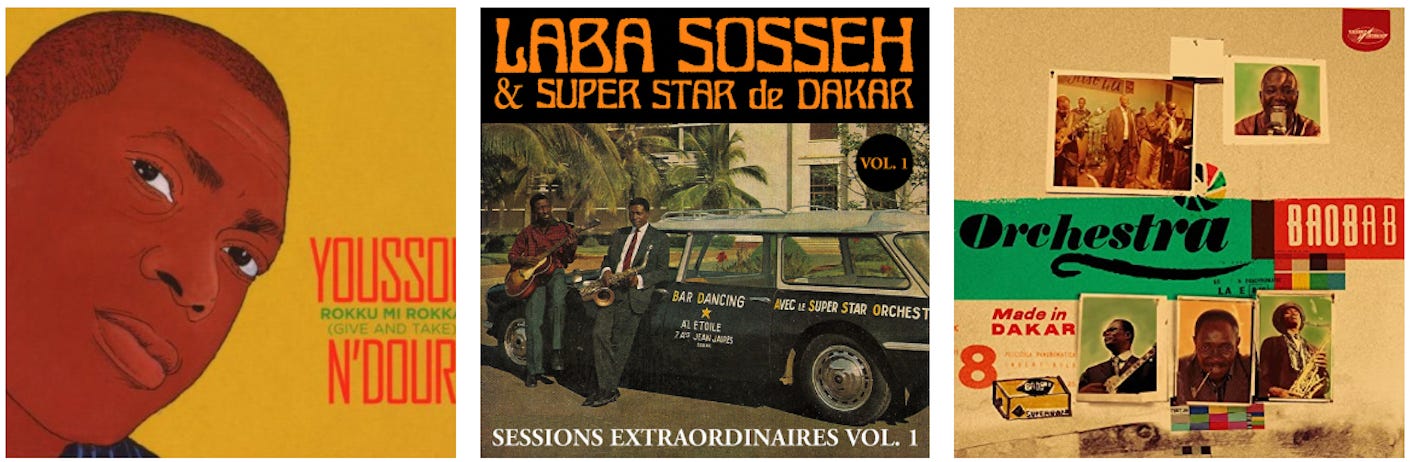

I didn’t spend the week of November 7 in Dakar because I expected the music to be fabulous. If that had been the idea, I wouldn’t have missed Saturday night to save on airfare, or picked the week Youssou N’Dour was in New York. Dakar is home to a lot of music I care about—N’Dour above all, the greatest pop musician alive as far as I’m concerned, followed by salsa-leaning Orchestra Baobab, the kings of the city until N’Dour’s more distinctively Dakarois mbalax dethroned them, then various lesser mbalax artists, plus Africa’s most deeply engaged rap scene.

But where the music of neighboring Mali has become a major export, Senegal has something like a functional economy, and its capital is the most urbane urban place between Cairo and Pretoria. This makes Dakar the cultural capital of Francophone West Africa, especially with Abidjan ripped apart by the Ivory Coast’s Christian-Muslim tensions, which the 95 percent Muslim Senegal is free of, in part because it’s Sufi, Islam’s most tolerant and also music-friendly strain. The city’s status as a musical destination is secondary to this larger status.

My base in Dakar wasn’t the Plateau, the downtown business district, or Les Almadies, where beaches and villas attract vacationers and the local rich. It was an unpretentious neighborhood called Baobab, where my friend and ex-student Drew Hinshaw shares a small house with his fiancée, Celeste Mason. Drew covers Senegal for Bloomberg News, writes freelance music journalism, and speaks French and Wolof; Celeste teaches fourth-graders and is learning both. Since I read French fairly well but speak it hardly at all, Drew and usually Celeste were invaluable companions on my explorations. But music was my companion, too, whether there was a show to go to or not. There were fabulous moments. But what impressed me was how pervasive it was.

SUNDAY: Just in getting oriented come two exemplary lesser moments. As we wend through a poor neighborhood near the huge, North Korean-built African Renaissance Monument, four skinny young girls notice the three toubabs coming down their alley. Instantly they form a tiny dance ensemble, raising their hands to shoulder height and jutting their chests in what I’m later told is last spring’s move. And at the jammed HLM market, where there are no CD stalls but four loudspeaker setups, three of them blast competing Youssou tracks that are complex and driving no matter how crackly. I own upwards of 20 N’Dour albums and Drew knows the recent hits—there’s one about power outages. Neither of us recognizes a single song.

Sunday’s only musical choice is open-air Just4U in the university district of Point E. Drew and Celeste saw Orchestra Baobab here just last night. The small mixed-race crowd includes a table that cheers on a mixed-race oud-trumpet-drum-vocal combo our waiter just calls “the Moroccans,” then splits with the band when their 20-minute set is finally over. But musos keep drifting in as midnight approaches, and on comes guitar-bearing 35-year-old Fulani vocalist Alioune Guissé, fronting kora and synth, bass and gourds, and two excellent female harmony-and-response singers. Guissé has studied traditional music at Senegal’s École des Arts, spent years in the U.S., and pursued trad-modern permutations throughout his marginal career—not a promising resume at a joint named after an imaginary Prince song.

But with his singers in sync and his brother-I-think scraping the gourds with a beaded device, he establishes a circular groove I hear as Malian, though it probably isn’t. It’s as trancelike as it’s supposed to be, which doesn’t always happen with such grooves, and for a while we’re psyched. But our attention flags the way attention does when you haven’t slept and can’t understand the words, so we prepare to leave when the next song ends. Only it doesn’t.

Unnoticed by me, the trance has become danceable, picking up half a notch as the backup singers power both tempo and melody. Dancers move forward, a few cavorting like those girls in the alley. Others cut steps in the rear. As the two women shout their hook, a tama drummer from nowhere beefs up the gourds. Twenty minutes in, I glance at my watch. It’s 12:48. The song goes on until 12:56 with no sense of strain. I’m reminded not of Prince, but of P-Funk.

MONDAY: Lunch in the Plateau with two N’Dour connections who will hook me up all week. Ashley Maher is a singer-songwriter with an apartment in L.A., a son in Accra, and a 2008 album called Amina that’s remarkably reminiscent of post-classic Joni Mitchell. She has a song on the European edition of N’Dour’s Rakka Mi Rakka album and in 2008 joined him onstage at Bercy in Paris to dance sabar, the full-service version of the move those girls busted yesterday. Babacar Thiam is a round, smiling, voluble, high-voiced multitasker who road-managed N’Dour until 2008 and now runs several businesses, including Orchestra Baobab’s career. He moved on after prying 125 visas from Senegal’s bureaucracy in the month before Bercy.

TUESDAY: I ask Drew to try a number I have for Serigne MBacké Fall, the director of Groupe Walfadjri, a centrist-progressive news organization comprising radio and TV stations and a daily paper. I figure he’ll blow us off but maybe take some questions later; instead he suggests dinner. Our connection is Rick Shain, a historian of Senegalese salsa, which with its synthesis of African rhythms and European sophistication was long the favored music of Senegal’s post-independence elite. A conversation impeded by my lousy French and Fall’s nonexistent English picks up when I recall the name of Kanda Bongo Man guitarist Diblo Dibala and his classic album Extra Ball, a title Fall writes in his notebook and underlines twice. He raves about a salsero unknown to me named Laba Sosseh; later Shain will send me an album whose heavy clavé converts me pronto. Fall is a progressive who believes hip-hop is pop’s only political hope but scorns samplers and keyboard beats. He’s a media mogul who confesses that he can’t watch TV at night because he's too busy with a record collection he enumerates down to the 45s. Driving us back to Baobab, he sticks an Orquesta Aragon CD in the slot. He knows every beat and dynamic twist as he sings along in unhalting Spanish.

WEDNESDAY: Music begins late in Dakar, so it’s almost 2 when Drew, myself, and a young American experimental composer-conductor named Nathan Fuhr arrive at le Ravin in Guediawaye, a planned commuter town fallen on hard times. There’s a racket going on as we duck down dark stairs to a dim open-air space, where atop the tuneless banging and ululation reigns a hefty woman in her 30s named Khady Mboup. Mboup says she sings goyane, from the Saloum delta south of Dakar. To me it sounds like Islamic devotional music that happens to be accompanied by a second female singer, four male drummers, two rhythm lutists, and a woman beating a plastic washtub with a special name—a pan. Only it’s Islamic devotional music to which dozens of Africans are dancing sabar far more vigorously and lasciviously than at Just4U.

Sabar is a body dance, all improvised torso bends, arm twists, and leg raises. I’m not surprised when Ashley Maher gets up—she’s a pro, with her own contained, confident, humorously unlascivious style. Nor am I surprised when Groupe Goorgoorlu, three male dancers with whom she’s been shooting an AIDS video, elaborate the music with indescribable rhythmic contortions. What surprises me is that avant-gardist Fuhr dances sabar too, and with panache, cockily mimicking if not quite matching Goorgoorlu shape for shape and gesture for gesture. As an elder, I’m exempted from the competition; approached by several cleavage-flaunting celebrants, young Drew boogies and bears it. The hour-plus set is both foreign and mortal enough to lose me at times, and eventually what seemed surreally intense normalizes. But in a lifetime of going out to music, this ranks with the most unlikely shows I’ve seen—dozens of African men and women in a disintegrating housing development seeking late-night transcendence whose full emotional or is it spiritual import? I wouldn’t dare guess.

Between sets, Drew and Nathan remember that they have to work in the morning. It’s around 3:30. I would have stayed, I swear it.

THURSDAY: While Drew writes, I try to make sense of the radio. Unable to understand the announcers, who range from sober to hyper just like in the States, I can’t locate N’Dour's or Walfadjri’s stations, but find that the American pop-rap Drew says dominates the discos comes up no more often than traditional grooves like Guissé’s or true Islamic devotional music, which proves much graver than what I heard last night, not to mention has no drums.

I confine the day’s research to N’Dour’s broadcasting operation, with essential help from Thiam—whether I’m messing up the place, the time, or my cell phone, Babacar is on his own phone bailing me out. First I taxi mistakenly to the radio station, located up narrow stairs in N’Dour’s crowded old Medina hood, which provides quite a contrast to the spacious new TV facility in Les Almadies. There my guide is Patrick Thomas, an articulate young Liberian who entered N’Dour’s employ shortly after approaching him at a concert. Senegalese president Abdoulaye Wade tried to deny N’Dour a satellite license, acceding only after N’Dour agreed to stick to “cultural” programming. But as Thomas introduces me to reporters, presenters, and techs—from not just Senegal but Mali, Chad, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, all under 35 except for a Belgian cameraman my age—they’ve clearly figured out that culture doesn’t just mean “the arts.” It means the whole life of a people. Do they do sports? Comedy? Sure. But also an “information magazine” and wide-ranging talk shows. And though they’re owned by the king of mbalax, a lot of hip-hop.

FRIDAY: In the Medina market we find a CD stall selling crude bootlegs for 1,000 CFAs—about two bucks. I’m happy with new mbalax siren Viviane Chedid and a board tape from one of N'Dour's Senegalese concerts. But the prize is a Youssou album featuring titles I don't recognize. It’s not like I have much memory for Wolof, but this time a Web search reveals that I’ve purchased an approximation of the Senegal-only Alssaama. Although collectors pretend N’Dour’s Senegal-only music is his truest, I believe he put Alssaama’s two best songs on his worldwide Rokku Mi Rakka. But it’s cool to have the others.

Everyone has told me N’Dour guitarist Mamadou Jimi Mbaye is a helluva guy, and that figures—why else would his not terribly well-sung 1997 Dakar Heart inspire such word-of-mouth? And when Ashley Maher reports that Mbaye, who played on her album Amina, is back from Europe, I find that he’s a helluva guy: gracious, candid, palpably intelligent. Although he has plenty of catching up to do with his two wives and newborn seventh child, he spends an hour with us, during which he nails a Bob Marley song, shows off his karate, and praises the politics of Senegalese hip-hop with fewer reservations than his contemporary Serigne MBacké Fall and with special praises for legendary ‘90s duo Positive Black Soul. He’s also surprisingly critical of his boss of 30 years. Although Mbaye gives me permission to quote him if I see fit—“We’ll have an argument, but it will be all right”—I have no desire to make trouble in the best band in the world, so I won’t go into detail beyond one brief sentence: “He likes power.” Back home, Dakar Heart starts sounding good. So does an advance of his forthcoming Khare Dounya, Auto-Tune and all.

Our scheduled entertainment is the well-regarded Yoro Ndiaye at Just4U, only Celeste latches onto a hot rumor: at Le Blue Note in Almadies, Awadi, who was half of the same Positive Black Soul Mbaye was just extolling, is playing. Can’t skip that. The delay that ensues after we pay 5,000 CFAs for an 11 o’clock show has nothing to do with what toubabs like to call “African time.” It’s rock club time in its purest form, so that when the music finally begins at 12:05, we’re stuck with not Awadi but a guitar-strummer in striped shirt and red Cons who for 40 minutes projects the soul-claiming self-regard that afflicts purveyors of musical sensitivity the world over. Soul-sapping though it is, this ordeal has the healthy side effect of deromanticizing Dakar, a place modern enough to have its own wankers. And in a departure from rock club time, there’s no intermission—Awadi fronts the same band as the guitar-strummer, and they’re so glad to see him that their groove roars and darkens the moment he hops onstage and pumps out his harsh staccato. Due at Just4U, Drew and I see half of a set Celeste tells us never faltered. She also buys me a 1000-CFA CD, the trilingual, pan-African Présidents d’Afrique, which, as rarely happens when rappers go solo, is both rougher and more sophisticated than his group work. There’s still the language problem that undercuts all international hip-hop crossovers, and Le Blue Note, after all, is a plush room full of toubabs. But if N’Dour’s people hope to shake things up with homegrown hip-hop, music like Awadi’s is why.

A personable, even-keeled low tenor of about 35 who’ll hit this year’s globalFEST in New York January 9, Yoro Ndaiye is the kind of well-spoken guy world music tastemakers love. Slicker than Alioune Guissé, he’s also solider and somewhat less trad, featuring a broadly schooled guitarist and an accomplished trap drummer who’s nevertheless less impressive than Awadi’s trap drummer. (Suspect African pop has stagnated along with its economy? Twenty years ago the continent’s only kitmaster of note was Fela’s Tony Allen.) Just4U is almost full as we squeeze into the back of a Hi-NRG finale that has Ashley high-stepping up front. And though the population density has decreased by the 2 o’clock set, the place is still hopping. Gradually, Drew and I are won over by Ndiaye’s musicality, and also by the big wooden balafon, an instrument that at its best sounds like a king-size xylophone with its tinkle dampened by packed earth.

Then there’s another long WTF moment. As the finale begins, a very black, fairly tall, slightly hunched blind man of 45 or 50 comes onstage. There’s banter from Ndiaye as he shrugs to the music, but when he opens up and sings, he’s got the stuff. Only soon he pales before the overt sexuality of café-au-lait young soprano Aida Samb, who is in turn topped by a brown-skinned fiftysomething in maroon skullcap and beige boubou who appears sedate, proves hilarious, and casually unleashes a throbbing baritone that blows the house down—only he’s then run through by a senior citizen who understands that when you’re old enough you can dumbfound the juveniles with just a few well-timed remnants of potency. Ndiaye later would fret to Maher that he should be tougher with guest performers. I think they made the night.

SATURDAY: On my last day, Babacar Thiam, who has been promising Orchestra Baobab all week, crams Drew, Celeste, myself, and himself into a cab that takes us to the handsome middle-class home of original member Rudy Gomis. Gomis and fellow vocalist Balla Sidibe have been in Baobab since 1970, as have the two absent members: crowd-pleasing saxophonist Issa Cissoko and, crucially, guitarist-mastermind Barthelemy Attisso, who still practices law in Togo, as he has since the band broke up in 1988. With Gomis and a few others flexing their English and Babacar and Drew translating, we have a warm hourlong conversation. Baobab are working on a new album that will feature American admirers Dave Matthews, Trey Anastasio, and hopefully Carlos Santana. Good move. But I’m more struck by the tale of how they reconvened. Baobab disbanded when their salsa variant, which dance nuts like Serigne Fall complain is too slow and I find gripping, even hypnotic, was rendered commercially obsolete by N’Dour's mbalax. They regrouped at the behest of World Circuit’s Nick Gold, who gave the world-music circuit Buena Vista Social Club. The hitch was that Attisso, thriving 1400 miles east of Dakar, wasn’t interested. So Youssou N’Dour called him up. You have to come back, N’Dour told him. Baobab can be a great band again. He was right, too—they’ve never been better. Obviously the man likes power. But pretty often he does good with it.

The three of us have dinner in the Plateau across the street from the Institut Francais, where a poetry slam I won’t understand is scheduled. But in one of the rare instances of African time I encounter all week, it’s late getting started. So we return to Baobab and play music I’ve brought till I have to go to the airport. Orchestra Baobab’s 1970 album, definitely. But also American hip-hop and then John Prine and Brad Paisley. We’re in Dakar, and it all sounds great. — MSN Music, December 30, 2010 & January 7 2011