The Big Lookback: Chuck D All Over the Map

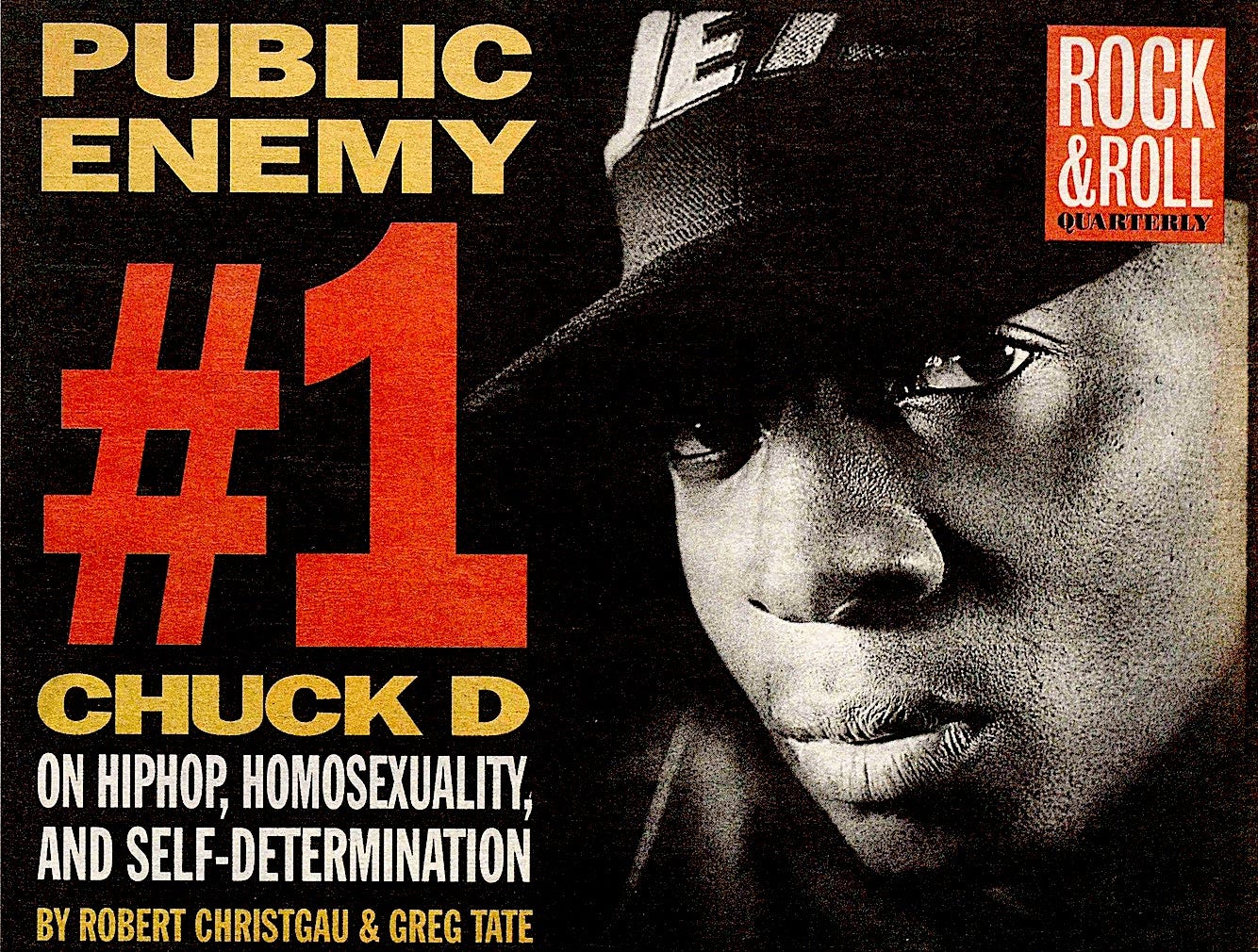

From the Village Voice, Oct. 22, 1991: Greg Tate and Robert Christgau interview Chuck D

The two nicest things the late and still painfully lamented Greg Tate ever said about me were that I “believed Afro-diasporic musics should on occasion be covered by people who weren’t strangers to those communities” and that my editing “was always intense, because he was 1,000 percent present. It was like life or death to him, the quality of the section, the quality of the writing.” What’s nicest about these compliments is that the first came in 2005 and the second in 2017, long after we were an item. It was 1981 when I began publishing Greg in the Village Voice under his original byline “Greg ‘Ironman’ Tate.” He relocated to Harlem from D.C. in 1982. But after the Voice music section passed from my hands in 1985 I edited him more sporadically, especially once he became a staff writer in 1987. And although we sure kept talking, only once did we publicly collaborate: in the 1991 Chuck D interview that serves as this month’s Big Lookback, which appeared in the Voice’s “Rock and Roll Quarterly” supplement. I got more of the Qs in this Q&A simply because I was the more aggressive guy—as flamboyant as Tate’s persona was, there was a self-effacing if by no means humble gentleness to the person. But we’d gabbed plenty about the homophobia question as we drove out, and that was big for Greg, a heterosexual male already well on his way to identifying, as his 2016 collection Flyboy 2 put it, “Black Lesbian gangsta feminist.”

As the published intro explained, Greg and I double-teamed the ever loquacious Chuck D at Public Enemy HQ in Hempstead, Strong Island, in the early autumn of 1991. That’s three decades ago now, when it was reasonable to expect Village Voice readers to be intimate with the controversy initially ignited by Public Enemy’s off-and-on, in-and-out, and eventually gone Minister of Information Professor Griff’s interview with David Mills of the Washington Times—a controversy few under 50 now recall. The curious should take a look at this wide-ranging 1989 summation by RJ Smith, then the not yet well-respected biographer (James Brown, Robert Frank, soon Chuck Berry!!) and historian (The Great Black Way) who Chuck D treats to an uncontextualized “I don’t like that motherfucker” toward the end; it provides a glimpse of what was involved, ignited above all by the unmistakable, unforgivable, and radically uninformed anti-Semitism of Griff's remarks (which it’s only fair to note he did eventually apologize for—sort of).

For sure there are other references that might confuse today’s reader. The St. Ides peroration refers to Ice Cube’s ad deal with that beverage, which as Chuck D recalls in his Fight the Power memoir irked him especially because he’d just changed a song called “A Million Body Bags” to “A Million Bottlebags” after concluding that “Black people drink malt liquor like it’s going in style” in part because “Malt liquor has a higher alcohol content than beer, but breweries usually won’t reveal the ingredients on the labels.” Dr. Frances Cress Welsing, who died in 2016, was a psychiatrist who held that whites were an inferior race who’d been driven out of Africa many ages ago. Molefi Kante Asante was and remains a leading Afrocentrist philosopher and activist. “Anita” refers to soul balladeer and crooner Anita Baker. The long colloquy on homophobia in which Tate takes such an active role turns largely on the suffix “phobia,” meaning irrational fear, which Chuck was hardly the only straight male of that time or indeed this one to regard as an insult to his courageous manhood. Rereading this conversation, I was struck by how very little interest Chuck evinces in not just romance but sex. But how sexist that does or doesn’t make him seems moot—he has always been one of the rare rappers whose rhymes very seldom demean women. It is very much worth noting that his wife of many years, Gaye Theresa Johnson, is a Ph.D who teaches in the Black Studies department at UCLA.

The day before Public Enemy’s monthlong tour with Anthrax began, we drove out to the nondescript Hempstead office building that Chuck D, Hank Shocklee, and their crew have occupied since they were running Long Island’s first hiphop sound system back in 1982. S1W’s, PE merchandisers, Media Assassin Harry Allen, and other employees contributed to the general hubbub. On the walls of the front office were samples of PE fashion: Spike Lee-style baseball shirts and hats, tour jackets, T-shirts, the whole nine. Chuck corralled us into a cramped conference room whose dominant feature was a map of the United States complete with zip codes. As he lectured us on the vagaries of hiphop as a national phenomenon, Chuck often rose from his chair and pointed to regions of the map to make himself clearer. The conversation began with Chuck interrogating Christgau about how he became a writer and ended with him apologizing to Tate for once branding him a Village Voice porch nigger. It lasted close to three hours, and for the most part Chuck didn’t duck our questions, although he did forestall them with his verbosity—as John Leland has said, Chuck may be louder than a bomb, but he’s a lot less succinct. Needless to say, what follows is an edited version.

1. Who Has Spare Time?

RC: How much input did the old crew have into Apocalypse 91? Hank, Keith, Eric—

CHUCK D: Hank is the mastermind of all.

RC: Was he on this record now?

CHUCK D: Yeah, that was Hank.

TATE: Y’all work like Miles, now, it’s just like, you come to the studio, you do your part, and it’s already there?

CHUCK D: No, it’s not like that. The Bomb Squad is still the Bomb Squad.

RC: Do you think there’s any musical evolution on the new record? Do you see it as being different musically as opposed to lyrically?

CHUCK D: The difference lyrically and difference musically is it’s more focused—it’s more hard. It’s sort of like Bum Rush the Show. Each album we do differently. I think I got real creative on the last one. Less creative on this one. You know, you venture off into different sounds and techniques and—

RC: The mix isn’t as dense, would you say?

CHUCK D: Of course. That was intentional. We hope to be trendsetters and not followers. The main difference on this is just tempo. We like to think of things as tempo first and not sound. Other people would probably say sonics before tempo. No. We’re in tune to tempo—we were the first rap group to really tempo it up, on “Bring the Noise.” That was 109 beats per minute. These tempos basically give you a Midwest, middle-of-the-country feel, with a little bit of east-west hard edge.

RC: How do the BPMs range?

CHUCK D: A lot of them are in the 96 to 102 range, which people will say is slow for PE, but then again, these are people that—what’s danceable here [points at East Coast on map] don’t mean shit. I just come from Kansas City.

RC: So the music is getting hard.

CHUCK D: On this album. I might just bug out on the next one. But when I bug out, it’s going to hit 85 to 90 per cent of the places. It might not hit here [points to New York] at all. But give me the rest, I’ll take it. Fear of a Black Planet was the most successful album we had—not because of all the hype and hysteria. It was a world record. Because of all the different feels and the different textures and the flow it had, I can do it—get the same feeling [more pointing] here, here, here, here, you know what I’m saying? Just in L.A., a kid is breaking down the rappers from different areas and he says, “Public Enemy, man, ain’t even like y’all from New York. It’s like y’all from somefuckingwhere— like, you’re fucking everywhere.” I say, “Well, we are from everywhere, and it reflects in our music, and it reflects in our lyrics, you know.” I’m a person—I ride on Greyhound through the middle. I ride Greyhound through Arkansas and Arizona. I’ll sit on Greyhound for hours just listening to my music, look out the window and write, you know. Yo, I just drove—went down to Disneyworld. I could drive like—see, there’s always a job in the business. Let’s say they say, “Chuck, you out of the business,” man, I’ll be a bus driver. I know the fucking roads, man.

RC: What do you do with your spare time?

CHUCK D: Who has spare time?

RC: Everybody has some spare time, man.

CHUCK D: Well, my business and my thing I like to do is more fun than anybody else’s—

RC: I live the same way, but nevertheless, I got leisure, you’ve got—

CHUCK D: Well, sometimes I just like to go in my fucking basement and just fucking watch fucking TV or videotapes. I can’t really watch too many movies. I usually like watching sports. I watch sports, you know—

RC: Do you listen to music much?

CHUCK D: I listen to Motown, I listen to a lot of tapes—usually when I’m on the road, when I’m on an airplane. When I’m home, I don’t really listen to music as much as I like to watch videos.

TATE: Music videos, or just—

CHUCK D: Music and sports. I can’t watch movies, really, except for black movies. I just seen Livin’ Large yesterday and you know, to the average person it might be like a three-cent movie, but I had a good time watching it. You know, me and a couple of the brothers’ families went out. I said, yeah, that’s some kind of dope.

RC: You listen to any jazz or blues?

CHUCK D: I wasn’t a jazz fanatic. My pops, like, was a jazz person—all that abstract shit. I was like, nah.

RC: Not for you?

CHUCK D: Not for me at all. I like blues more than jazz. ‘Cause blues deals with lyrics—more feeling, you know what I’m saying? And it has so much ironic twist in it—it’s usually about the slightest shit that black people talk about, you know, day by day. And I do a lot of hanging in places like down South, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Atlanta.

RC: Do you listen to any metal or white rock?

CHUCK D: Yeah, once in a while. I like watching the videos more than I like listening to it.

TATE: When you hang out down South, do you hang out in music clubs, or do you just hang?

CHUCK D: Music clubs, Beale Street, the whole nine. I always liked the blues. But I’ve liked it more since I’ve been able to go to these places.

RC: It would be great to sample some of that shit. You hear very little in the way of blues samples.

CHUCK D: Well, you know, musically it moves me, but lyrically, man, I’ll be like saying, Goddamn. And that’s why I try to move a lot of rapping and rap music the same. At the end of the day, I don’t know what the fuck you write about, just make somebody just say, Damn, you know. That is a good point of view, you know what I’m saying? I mean, look at N.W.A.—you might not agree with what the fuck they’re saying, but you at least know at the end of the song, like, yo, these motherfuckers meant what they’re saying, you know?

2. Hardcore Responsibility

TATE: People talk about the positive and negative images of rap, and then there’s a whole other line of thought that says the music is important no matter what it’s talking about ‘cause it’s creating a forum for discussion.

CHUCK D: It’s important to be positive because you got to understand, the only time the structure wants to put anybody black up there in the spotlights if we are athletes or entertainers. If all the athletes and entertainers are going to get projected like that, we’ve got to say, damn, we’ve got a little bit more responsibility than the average white musician that comes along and just wants to talk about his dick. ‘Cause we’ve got to say, all right, yeah, this is a story to tell, but at the same time, this is probably going to be the result of it. I mean, I talk about a drive-by, I might start drive-bys in St. Louis. That’s a tight line, and we’ve got to deal with it, ‘cause we're going to be listened, watched, and followed a lot closer than a lot of white kids.

RC: But you just said N.W.A. at least had their own point of view—

CHUCK D: They’ve got their own point of view, that’s coming from and artistic point of view, but socially—

RC: You’ve got your doubts about that sort of representation?

CHUCK D: ‘Cause I see the fucking results of it. And you got to have a structure in the society, in the school system, that’s able to say well, this is the right, and this is the wrong. We could say that families are supposed to do it, but we ain’t got family the way it’s supposed to be. So I mean, we’ve got to go to a school or structure that can teach us family.

RC: You got kids yourself?

CHUCK D: I got a daughter.

RC: How old is she?

CHUCK D: She’s going to be three next week. And you know, that shit is a motherfucking task. [Laughter.]

RC: I know. I got a daughter, Greg’s got a daughter.

CHUCK D: I’m saying, you know, people have to be taught how to do certain things. And then, let’s go back to the music, the positive and the negative. A guy’s going to talk negative shit because that’s what he sees. Rappers only talk what they know. I mean, sometimes you’ve got people going off into the fantasy world, like the Geto Boys when they talk about mind playing tricks on me, Chuckie and stuff like that, and make analogies saying, well, you can’t talk about me because, hey, all those fucking crazy movies coming out an nobody’s getting any heat for that. But we have a double-edged sword hanging over our head, a guillotine, that’s saying, well, we do this, we’re going to be followed—you know, people going to do this shit in reality. And I believe that.

‘Cause, I mean, everywhere I go, I mean, I go to prisons, and, you know, brothers—if they get no guidance from zero to 16, they’re going to follow something that can relate to them best. And if something can relate to them best that they really, really like, they’re going to follow it. They’re going to say, “I got to kick this motherfucker tonight.” Boom, boom, boom. And later on, they’ll be like, “Damn, damn.” Like that brother that got to go to the fucking joint now for killing that Jewish guy. And ain’t nobody fucking behind him now. He gotta go to the fucking joint. He gonna get fried. Somebody didn’t tell him to put his brain in gear. Now he’s gotta suffer the consequences. I feel sorry for him. Because I’ve talked to a lot of brothers in jail and usually brothers in jail are in for impulse. Boom!

That’s why I started talking about the “1 Million Bottle Bags.” Because I tell you a lot of shit be starting off because of distorted thinking like, damn, usually brothers that know each other, be like drinking. They be like, “What you say?” “I ain’t say shit, man.” “Your fucking mother.” And then somebody got a fucking nine or Uzi in the territory, and the shit escalate to even a higher pitch, couple of people in there going, “Yo, just, chill, chill, chill.” And sometimes you get, you know, “Fuck that, motherfucker.” And it all be starting up because motherfuckers is fucked up.

RC: Do you drink at all?

CHUCK D: I don’t drink. My crew don’t even touch meat. Me, I eat it, if my wife cooks it at the crib.

TATE: Did you talk with Ice Cube about the St. Ides thing?

CHUCK D: Yeah, I mean I briefed it on him. You know, he said, “Yo, man, just trying to get out of it.” Trying to stop it, but he’s contracted. I said, “Yo, Cube, hey, there ain’t nothing against you, I mean, it’s your thing, your guilt thing, but you should have had quality control.” The people at St. Ides said, “Well, we really respect you Chuck D, you know.” I told ‘em I don’t respect y’all, fuck y’all. I see the results. I’m not just fucking reading stats. You’re in the black community, you can run, you can’t hide. There ain’t nowhere you can go and live and say, well, I’m going to be far away from it. Nowhere.

I’m seeing results whether it be Memphis, Houston, St. Louis, Chicago, Detroit—it could be the smaller fucking cities. I’ll take you right in the ‘Velt, Roosevelt—one square mile. Got 14 delis in there, and every single deli got Ice Cube’s poster. The people say, “Well, why do you give so much of a damn?” Because I’ve got to live in this motherfucker. And I’m grown. Once you’re over 18, fun and games got to be put to number three. Responsibility and business got to be one and two and you can have fun and games and shit, but once you understand those number one and two things, you understand that fun and games are being played on your ass. I tell motherfuckers in a minute, you can be hardcore and be positive. Thieves and pimps and murderers, man, motherfuckers got to pay a penalty. The problem is that some white boy coming in and trying to remedy the situation and we need to start doing it ourselves. The more grown people you have that understand they’re adults and take control of their community, the less bullshit you have coming in. And you used to have something like that until quote unquote so-called integration.

TATE: Desegregation.

CHUCK D: Yeah, right.

TATE: That’s what the older folks used to talk about. If you were doing any kind of crime, you just knew not to do it in nobody’s face. If you were drinking, you didn’t drink in public, you didn’t fall down in the street.

CHUCK D: It was a time, right. It was hardcore. Hardcore will never die and need to come back. You can be positive in the hardcore. Hardcore got this connotation that other people put on it of saying that it’s negative and no, no—hardcore, it’s like you taking control. I tell brothers, you say you hard, but your life harder than you. How hard can you be? Your life kicking you in the ass. Fucking world is harder than any motherfucker.

This stuff should be coming to people when they’re three, four. Especially young black males, three, four, seven, eight. And it gotta come every day. That’s what the father does, is supposed to do. I mean, my pops had to work, but my pops was able to give it to me at the right time. And I think the key is in the black structure in society. We have to rebuild the black man, young black males got to built to be men. And then you will start seeing a clearer picture, you know. It’s a lot more simple than it is complex.

And I think that’s something that definitely got to be taught through the school systems. I mean a lot of things have to be taught to us. Once again, I go back to slavery. Slavery has done a lot of fucking detriment, where it’s almost irreparable unless we’re going to fucking eight-hour-a-day training sessions that satisfy our intellect but also satisfy our wants and needs, you know. I mean, mentally and physically. School’s got to be school. And a school for black people, black kids, definitely it got to be different from white kids.

The remedies and how it can get done is all in the government’s hands. We talk about reparations, I’m not talking about sending everybody a fucking $10,000 check. If you went outside and gave motherfuckers $10,000 each, those motherfuckers wouldn’t know what the fuck to do with it. I’m saying, you got to have a fucking training programming medium so people will be able to say, well, damn, now I’m being taught to think.

TATE: That kind of begs the question of whether the government wouldn’t just as soon black people stay where they are.

CHUCK D: I don’t think the government wants to see that happen. First of all, they’re saying we’re only 10 per cent, so we have to submit to whatever goes down. But we’re a growing quote unquote 10 per cent. And in order for them to satisfy black people in the year 2000 they better come up with some shit. They already came up with a result of genocide that got us fucking each other up. I’m saying, we need to come out of that dead zone. We come out of that dead zone then we can talk about plan two, three or four. It’s either got to be his way or it’s going to be fucked up, it’s going to be crazy. That’s why I said, “Welcome to the Terrordome.” I wrote that record at the end of ‘89, to signify the Terrordome is the 1990s. It’s a make-it-or-break-it period for us. We do the right thing, we'll be able to pull into the 21st century with some kind of program. We do the wrong thing, the 21st century is going to be gone, there’ll be no coming back.

RC: I buy that.

CHUCK D: I don’t know how much effect it has—I’m not here to judge effect or results. A lot of times, the weight that lot of people put on Public Enemy is because they don’t see these other things. When I first did Public Enemy my role was bring information, saying, “Well, bro, there’s a Karenga, there’s a Farrakhan, there’s people out there that have been studying in whatever field. There’s a Dr. Welsing. Check these people out. We need to get into it, ‘cause these people have put in 40 or 50 years of unacknowledged time, for the benefit of where we should go.”

But Public Enemy’s just one fucking thing. I’m only one motherfucking person. And I’m saying to each and every black person, you look in your family—it might not be your immediate family—you’re gonna find either murder, drugs, alcohol abuse, and disease, or jail, somebody getting jailed. I’m saying you can run but you can’t hide. Which means that everybody gotta be able to at least work forward or try to remedy the situation.

TATE: You’re really talking about personal accountability. You’re not in this necessarily believing you’re going to change the world.

CHUCK D: No, no, of course not. There’s no one motherfucker that can change the world. I’m saying that my fucking job as an adult is just to make sure that my community is all right for me—or whoever, a child or adult—to live in.

3. TCB

TATE: When I saw you down at the conference in D.C., on one of the panels you said, “Yeah, a lot of people think I spend a lot of time reading this, that, and the other thing. The one thing that I really study is the music business.” How did you become so fanatical about the business?

CHUCK D: I approached Hank back when he was a monster DJ out here—I used to be a fan of theirs [Spectrum City, Hank’s sound system]. I just saw that one of the gigs I went to there wasn’t enough people there, and I came up to Hank out of nowhere and tried to explain that it was presented wrong. I thought, you know, in order to catch people’s attention, you know, fliers should be done in the same way most black people buy things. And later on, I was just toying around on the mike at Adelphi. They had never really allowed MCs, and I guess I was the one. Hank liked me because of the way I sound. So we became partners in ‘79, and we would wait for people to hire us. But that begun to be a dead-end road because you always dealt with somebody that wanted to rip you off. So that’s when you say, “Yo, man, we rocking the house, but somebody’s always leaving out the back door with the money.” So I say, “Yo, man, look, we going to do this. I keep the people busy and you keep that person at the door.”

TATE: The both of your families are businesspeople?

CHUCK D: My father had his own business at 40 after he went through the same bullshit in the white corporation, and he was working in the corporation for 20-some-odd years and all of a sudden they had a fucking attitude of, you know, well, maybe he could go somewhere else.

TATE: What kind of a corporation was it?

CHUCK D: The fabric business—979 Third Avenue, the D&D building. He worked in a couple of companies in the fabric business. Jack-of-all-trades. But his official title was really shipping and receiving manager, you know, warehouse manager. He knew all about the business.

RC: And then what’d he start to do at 40?

CHUCK D: He just dropped it and what he did, all his contacts and all his friends, he started a trucking company that dealt with undercutting the other trucking companies. It was rocky for about two years and then it coasted. Still was a battle, because it was a lone one-man thing, battling the structure. But I learned a lot from my father. He just said, you know, if I’m making less, fuck it. Eventually, you know, what it gives you in peace of mind is more important. My moms couldn’t understand it, you know, but then later on she did. But that move taught me a lot. It just showed me that business is the only way to go. I don’t care if I’m making $10 on my own, it’s better than getting $100 from somewhere and you don’t know where it’s coming from.

RC: What were you doing between ‘79 and ‘84?

CHUCK D: ‘79 and ‘84 we was what you’d call the hiphop movement in Long Island, Queens.

RC: And you were making money off of hiphop?

CHUCK D: Yeah, we was making money. Paying bills. Wasn’t making profit, but we was paying bills. And what drove us is, like, yo, you’ve got to pay these bills. Lighting and rent and shit like that.

RC: So you weren’t making a profit. How were you eating?

CHUCK D: I was in college just like you.

4. Out of One People, Many Afrocentrisms

TATE: One of the things that you read all the time about all the rappers that come from the suburbs—there’s this idea ‘cause you’re in the suburbs, you don’t know anything racism, discrimination.

CHUCK D: That’s bullshit. There’s apartheid out here like a motherfucker. There’s a lot of black people out here but it’s in pockets. Roosevelt is one square mile but in Merrick it’s like no blacks there. You know, they ask for ID—how is that different from a pass?

TATE: I have a friend that grew up in Elmont. Right next to her neighborhood is this huge high school. And they rezoned her neighborhood out of that, so it’s still like a predominantly white high school.

CHUCK D: If you look into cities, cities are just places that say, come on up from down there so we can put y’all in one area, stack y’all on top of each other, we’ll make it easy for you to get you a job. And that’s why we’re catching so much hell in cities today. People are saying, “What about the Crown Heights thing, the Brooklyn situation?” I say, Brooklyn’s a fucked up place to be. The shit ain’t right for you. The place is getting packed and packed, more and more, they stacking people on top, and there’s no way to fucking have a clear fucking type of thinking there, you know, when you’re all tight with everybody. And then when you’ve got two fucking communities just getting bigger and bigger, forcing into each other, shit’s going to break wild if everybody don’t get no explanations on how to take care of themselves. The city ain’t never been right for us, you know what I’m saying? I always look back, like in Africa, we were always nomadic people. You know, shit get crazy—go, move, you know what I’m saying? Get the fuck on out of town.

TATE: You were in a program that was run by the Panthers, right?

CHUCK D: It was two years, summer school. At their house. Panthers, Islamic brothers, just brothers from the neighborhood, students, you know. And it was the thing that turned me around, turned a lot of us around. It wasn’t like what it gave us then. We noticed it years later. You know, “Hey, remember African American Experience?” At this time in America, around ‘77 and ‘78, motherfuckers was like laughing at dashikis, and we said, “Damn, that shit was sort of fly back then.” We’re not saying we would wear them, but, you know, we had a respect for that. Whereas a lot of kids in other areas was like, “What?” And it came up the roots that that supplementary education gave us. These guys and these sisters weren’t saying don’t go to school, which a lot of people were using as an excuse: “Oh man, school ain’t teaching me what I need to know.” Yeah, but you got to know that because right now we have a lot of people in America, we have potential and talent for a lot of different things but we’re unskilled.

RC: So you're in favor of an Afrocentric curriculum, obviously.

CHUCK D: It’s the only key to our survival.

RC: Can you tell me what Afrocentric thinkers you especially relate to? Do you read a lot of this stuff?

CHUCK D: I read a lot of it. But you know, basically, it’s the same story interrelated.

RC: Wait—give me a couple of names. Asante, Williams.

CHUCK D: Ah, man, come on. Asante’s cool, you know, Karenga. I mean, everybody—I think a lot of brothers, I mean, going back to Marcus, got concrete plans. A lot of brothers had concrete plans for the time, but then again, we have to realize, times, they’ve really changed.

I think all the black philosophers have something in line. Like people talk about Stanley Crouch, how much of an asshole he is. I think, deep down, he wants to see something better for black people even though he might sound like an asshole. It’s just that a lot of brothers that fight for the struggle, they fight for the struggle so long that they get beat down by white supremacy and don’t realize it. So their views become so radical that every time you hear their mouth they sound like, “This nigger antiblack or what?”

RC: Do you think the aspect of Afrocentric theory that’s about the greatness of ancient black civilizations is as important as it’s made out to be? Or are you more interested in contemporary history, all the aftereffects of the slave trade?

CHUCK D: Contemporary stuff. I think that’s important. But I’m really dealing with everything. History is everything. White capitalism, white supremacy, slave trade, movement of blacks, and black people catching hell all over. That takes studying. And a motherfucker in the eighth grade should have that down. Those are the basics. You don’t understand that shit from fourth to eighth grade and it doesn’t get drilled into you and it doesn’t make you feel good. Learning should be feeling good like a motherfucker. Learning should be something like, “Damn, man, I’m learning a lot today.”

You know, you walk into a fourth and fifth grade, in a black school—quote unquote black school—today, I’m telling you, you’re finding chaos right now, ‘cause rappers came in the game and threw that confusing element in it, and now kids is like, “Yo, fuck this motherfuck.” School, I’m telling you, the educational system from here to here is at war, I’m telling you. In the ‘90s, by 1995, it’s gone. I’ll tell you, I do speaking engagements, I went to fucking Evansville. White high school. Eighty per cent white. And every one of the white kids is number one like this, “What's up man, uh, yo. [Laughs] Yo, thanks a lot man, y’all teaching us a different perspective, because I can take so much of this Patrick Henry bullshit.”

RC: Well, now that you’ve set up this expectation, and you'‘e got this fucked up school system, do you think this school system is so fucked up that it’s just as well that they ain’t listening? Or don’t you think it might be a good idea for them to learn how to do their addition and read and write?

CHUCK D: It don't take mothers long to take skills down. They spread it, they try to make it interesting, you know what I’m saying? Skills is skills. To get those basic skills down--they spread it so fucking far apart, 12 years, and you're taking 12 years of skills. There’s some of them are unnecessary skills. If you had kids saying, well, damn, I want to, like, put Nintendo computers together, it might be advantageous for you to—well, you better do good in calculus or trig or some shit like that.

So I don’t make some statement like, yeah, I hope to make some money to send my daughter to college. I hope to make some businesses that she can run. And that’s the fucking thing about capitalism—we as black people keep looking for fucking jobs, we ain’t getting no jobs ‘cause there’s a tight rope on white business, and they definitely ain’t giving a black face a fucking job because business is family.

RC: It’s Farrakhan’s orientation to that kind of thing that you like best about his program.

CHUCK D: A lot of things I like best. You can’t say it’s just that one thing. But, yes, self-sufficiency is the best program.

RC: Do you think he’s actually achieved that?

CHUCK D: Farrakhan’s one man.

RC: I know that. I’m talking about the NOI [Nation of Islam]. Do you think the NOI is actually—

CHUCK D: NOI is full of individuals that treat it like an organization and many brothers in the NOI have small businesses. It’s not just some big fucking corporation juggernaut. Basically, it’s an organization of united brothers and sisters around the country that say, “Yo, now, we're going to do for ourselves.”

RC: Do you buy the notion that some sort of an African-centered religion might be very useful in making this happen, in giving this sense of community? Not necessarily the NOI, but say the kind of thing Asante talks about.

CHUCK D: No, I just think that we could still have the various different philosophies and different viewpoints of life. Everybody ain’t made out of a cookie cutter. Everybody’s got different opinions—everybody got different tastes and different feelings on how they want to look at life. It’s only, there’s a right way and there’s a wrong way, you know what I’m saying? The wrong way is getting in somebody’s path and disrespecting nature, which is God’s plan—we only got one place we know we and other human beings can live. And the white structure and the European structure has proven contrary to both. It’s fucked up other human beings, and it’s fucked up the planet.

5. Carlton Ridenhour as Chuck D

RC: Visually, how do you project your own persona? Do you think about how you look?

CHUCK D: Do I look in the mirror and bust pimples?

RC: No, I’m just talking about how you present yourself visually, how you think about that.

CHUCK D: Well, out of strength. Back in the day, I was like the first to put on a black Raiders hat, because it was a black hat. One of the few black hats you could find. The Raiders had kind of silver and black, and I said, “Well why not, kind of dope.” They didn’t make Raiders hats, I would have been in trouble.

RC: So you do think about this. Now broaden it out a little bit: how was Chuck D different from Carlton Ridenhour?

CHUCK D: Because he is on the wall. Ain’t no different. Maybe it’s a little different five years later, because I know that I’m older and I got more responsibility, but shit, it’s not that much different.

RC: You set yourself up as a teacher, right?

CHUCK D: I set myself up as not only a teacher, but an older brother. ‘Cause when I was working the hiphop, you know, people were saying, “Why y’all fucking with them kids?” When me and Hank first got involved, we said, “Yo, man, we into the music, we’re going to give our communities something, some kind of outlet”—15-, 16-, 17-year-old brothers. ‘Cause older brothers was what? Either being locked up, going off into the working world, and saying, “Well, fuck it, I got my thing.” Or they were going into the fucking army, especially the army. But what they would leave is a whole bunch of brothers, 16, 15, 14, 13, with no direction. And they wasn’t really listening to their parents. Once again, there’s a lot of single parents and then the parents that was there—there’s such a gap, you know what I'm saying? Brother come home, bring home his Run-D.M.C., and the father, he only into his fucking Anita, you know what I’m saying? And never the two would communicate.

Other people came and said, “Damn, saying you’re older in rap is like taboo.” I started making records when I was 26. So I just threw all that shit out the window. ‘Cause when I was growing up, I liked the Tempts. You didn’t look at them as being old motherfucking men. O’Jays—bad as a motherfucker. So I said, well, basically your older brother can communicate to younger brothers ‘cause younger brothers want to get to where their older brothers are. I got a car, I ain’t got to go to school no more, and I’m working. I got a little bit of money with me. Somebody 14 saying, “Hey, it ain’t bad. I can relate to some of that.”

RC: Do you think that your fans think you’re wiser, more knowledgeable that you actually are?

CHUCK D: I’m using age as a weapon. Me and Ice-T probably talk to more brothers than anyone. And Ice-T got a couple of years on me. I say, “Look man, I been through what you did and some.” And they’re, “Bro, fuck it, man, you got this and you got that.” I say, “Still black in America. I know exactly where you heading to.”

6. Who to Sock It To

TATE: There was an article, long time ago, where you were quoted as saying, there’s no way a homosexual could be a black leader. And there’s also that whole charge that you’re homophobic—

CHUCK D: I’m not afraid of them. I’m just not one. I’m not on that side. I’m just not on that side.

TATE: Yeah, but what does that mean about how you feel about people who are on that side?

CHUCK D: That’s their thing. Do what they want to do. I can’t tell them who to sock it to. I mean, that’s their thing. Would I let a homosexual in my kitchen to eat dinner? Yeah, why not? Would I let him into my room while I’m sleeping—

RC: Well, but I’m sure no homosexual is interested.

CHUCK D: How could I be afraid of a homosexual? Can’t be afraid of them.

TATE: A lot of people are afraid of them. Afraid of what they represent.

RC: Or they’re afraid of what might be inside themselves, too.

CHUCK D: I think they’re a little confused. That’s my personal viewpoint. Love got a distorted fucking viewpoint on it. Who gives anybody a badge to say what love is? Love—homosexuals can come from lack of love as well. From somebody not really knowing what true love is. Heterosexuality—a lot of people think it’s love is not love either, you know what I’m saying? Love can be a concern, it can even not be sexual.

RC: You’re not saying that homosexuals who love other men don’t really love them?

CHUCK D: No, I’m not saying that at all. They can love them all they want. I won’t love them. Not in that way.

RC: Do you think there could be a—

CHUCK D: A homosexual leader?

RC: Black leader? Bayard Rustin, for instance?

CHUCK D: Leader—why would sexuality have something to do with it?

RC: Don;t ask me.

CHUCK D: I don’t come out and say, “Yo, man, I'm a heterosexual.” So why does your sexuality have to do with anything? What business is it—

RC: I’m glad to hear you say that, Chuck. That’s the way I feel about it.

CHUCK D: But no, this is what I’m saying. A lot of homosexuals, they call it out of the closet. They use it as a badge. That ain’t no badge. It’s like somebody going and saying, “Yeah, well I fucked nine bitches three weeks ago.”

RC: It’s a badge because it’s a source of oppression, that’s why.

CHUCK D: They use it as a badge, I’m telling you. What the fuck does your sexuality have to do with anything?

RC: It can have a lot to do with whether you’re free to live your life the way you want to live it.

TATE: It wouldn’t be no issue if people weren’t kicking people's asses.

CHUCK D: No, no, no. Number one, I think—this is number one—it’s like this: If sexuality becomes an issue, then the fucking society, twisted as it is, it’s going to come out like it’s going to come out. I’m like saying, what’s the fucking whole point of pushing it—all right, yeah, I’m fucking these motherfuckers, but accept me anyway. I don’t give a fuck who you’re fucking.

RC: A lot of people do, Chuck.

CHUCK D: It’s a waste of time.

RC: I’m glad to hear you say that but it worries me when homosexuals or perceived homosexuals get beaten up by straights, for whatever reason.

CHUCK D: But why would anybody wear sexuality as a badge?

RC: Because they’re oppressed as a result of it.

CHUCK D: You think they’re oppressed ‘cause of them wearing it as a badge.

RC: I think they’re oppressed because they’re gay.

TATE: It’s like, historically what happens is somebody says, “That motherfucker’s a faggot, I’m going to kick his ass.” It’s not like this person’s going around wearing a placard, but it’s because of the prejudice that exists toward this person’s sexuality. They get oppressed.

CHUCK D: My whole point is like nobody—you know, this is an average thing in the neighborhoods, like, homeboy was just with a girl, right? And usually in the neighborhoods, it’s like, motherfucker’s got to tell a story. Like, all right, that you getting that pussy. I don’t want to hear that. You know, I’m bored with you, let’s talk about something that’s constructive, not you getting that ass, you know what I’m saying? That’s the same thing, it’s like, that’s bullshit talk.

TATE: It’s like if you espouse black nationalist philosophy you’re going to get your ass kicked in this society. But nine times out of ten, if you believe in it, you’re going to put that shit out there, ‘cause that’s what you believe.

CHUCK D: That ain’t got nothing to do with my sexuality. Somebody come over and say—suppose my point of view is like this: I’m Chuck D, I ain’t fucking no white bitches. What’s the point of that? I say, “Yo, I don’t like white women, black women is what I like.” You know what I’m saying? That’s not even a point. That’s not even the issue. A lot of things is behind the closet. A lot of things should remain behind the closet, you know what I’m saying? A lot of things should remain behind closed doors. True or false?

RC: Not necessarily, Chuck.

TATE: It’s like, your sex life is probably behind closed doors. But somebody sees you in the street and decides they’re going to kick your ass ‘cause—

RC: Or if you’re told you can’t teach elementary school because you’re gay, which happens, that’s bullshit. And gay people have to protect themselves against that.

CHUCK D: This is what I’m saying. A motherfucker goes out, and he’s effeminate or whatever, and the mother going to beat him up, that’s a stupid motherfucker. But if that causes people to come out and say, Yeah, fuck it, I’m gay. I’m like saying, All right, OK.

TATE: But that’s usually why people do become militant—because somebody’s trying to destroy them because of their identity.

CHUCK D: But there’s still some things that—I don’t know—that’s just a personal point of view. I think more gays, you know—their business is their business. That’s my whole thing. Do the job. Why should the sexuality be a fucking postcard? This is who I like fucking, this is who I’m in love with. If I came out and said, This is what I like fucking and this is my fucking agenda, I’m not really getting the job done.

RC: I just want to see if I can get a straight answer. Do you think that there’s prejudice against gay people in this society?

CHUCK D: Of course there’s prejudice, but at the same time I understand that a lot of it—I don't want to say that it’s brought on themselves. I say a lot of it should remain behind closed doors.

RC: All right. Circle again.

CHUCK D: That’s my feeling. Because if, it comes out it really is—

RC: Do you think it’s right to contribute to that prejudice?

CHUCK D: No.

RC: When Flav says Cagney beat up a fag in the New York Post song--

CHUCK D: Flavor doesn’t like homos. And a lot of people say, “Yo, man, fuck them.” Look, you’re asking me, you’re talking to me—

RC: I mean, if we’re all human beings, and all the rest of that nice talk, so are homosexuals, and they ought to be treated like human beings.

CHUCK D: Well, treat them like human beings. I’m saying that’s cool. I mean, I ride a train with one, I ride a bus with one. I'll even do business with one. I do business with them all the time. I’ve been doing business since I was fucking 12—in the D&D building—got nothing but homosexuals in it. That was one of my first jobs. My father always said, those are the people, this is what they do. You do what you do, they do what they do and call it a day. My whole thing is—it doesn’t become an issue with me. It’s a waste of my fucking time. Talking about homosexuality is almost like talking about Jews, you know, it’s a waste of my fucking time. I don’t spend much of my day talking about either.

RC: Or thinking, I’m sure.

CHUCK D: Like, yo, their thing is their thing, you know what I’m saying? My whole thing is usually black people. And to anybody whoever might do whatever they want to do, it’s like, Yo, that’s your program, you know what I’m saying? And when people ask me questions about it, sometimes, it gets difficult, because I’m like, you know, I haven’t studied other people’s religions to tell them this and that. You know a lot of times when you talk about Jewish people, I would like to say, I don’t know. Here in America I look at things in black and white, I’m not breaking down nobody’s classification.

7. Hard and Soft

RC: On the new record, there’s an anti-Quiet Storm song [“How to Kill a Radio Consultant”].

CHUCK D: I hate Quiet Storm. My wife loves that shit. I don’t understand it.

TATE: Boy-girl thing.

CHUCK D: All you fucking do is go to sleep to that shit.

RC: Well, no, there’s other things you can do. But that’s behind closed doors, Chuck. Many would say it’s good fucking music.

CHUCK D: I think a beat is better.

RC: But do you think romantic music is escapist bullshit? Is that how you feel about it?

CHUCK D: To me personally, I think it was better r&b in the ‘60s. It ain’t because I’m trying to sound like an old motherfucker, but I just think that more heart and soul went into the concern over the lyrics and the lyrics led somewhere. The brothers back then and sisters back then sang a tune and the lyrics was kicking, and the music was felt. I mean, you know, today, I mean I love the fuck out of BBD [Bell Biv Devoe] and shit, ‘cause it’s something I can relate to, I like Keith Sweat, and I like a lot of new guys. But I can’t go too much past them.

RC: Not even Luther?

CHUCK D: I respect Luther as a skilled artist. Whether he’s my skilled artist? I brought Power of Love to the crib, I have doubts I’ll be cracking it, though. Not my cup of tea.

RC: I know the feeling. But there’s a sense in which PE’s music is very much boys’ music.

CHUCK D: Right.

RC: Do you think that those hard beats express everything that you want to be, spiritually? I like hard beats a lot. But I also want to be compassionate, sensitive, as well as angry. PE’s music—it’s so militantly unromantic.

CHUCK D: But it romanticizes certain things that we tend to ignore. I mean—I wrote a love song, “98” [“You're Gonna Get Yours”]. That was my love song, man. It wasn’t that that 98 was all there—barely had four wheels, man. But that was my motherfucking shit, you know.

RC: Do you think you can do a song like that about women, about love and women? ‘Cause you don’t do it at all.

CHUCK D: Why should I write that song? I’ll leave that up to Luther.

RC: Because if creating strong young black men is what your central thing is about, and you’re deep into the family, then it seems to be that there’s a place where hard beats stop, spiritually. It can get you so far.

CHUCK D: There’s a place where hard beats stop. And it stops at the end of my record. You want to listen to something that’s mellow, then you want to listen to somebody else. L.L. might give you that song. Bobby Brown might give it to you.

RC: And you hope somebody does.

CHUCK D: Somebody does, anyway. I tell you what I think, though, I just feel like cursing is kind of played. The Geto Boys took it as far as you could take it. When I went down South, the album that I could play that met the medium of everybody in the car—my sister-in-law, and my other sister-in-law, she’s 14, my daughter, my niece, they’re like three and four, my wife—so you know, I was surrounded by Apaches, I can’t be playing Boyz N the Hood soundtrack now. I got my tapes here—can’t play Robin Harris. You know who we ended up playing six times? L.L. Mama Said Knock You Out. It was hard enough for me, nice enough for the wife. It’s like the hardest pop record ever made. He made a fucking hard album without cursing.

8. It’s a Black Thing, You Got to Understand

RC: You just toured with the Sisters of Mercy and you’re touring with Anthrax now too? Would you say you’re targeting the white audience, or it’s just what happened?

CHUCK D: It’s just what happened.

RC: You said that the 1990s were a crucial time for black people in this country. At your most optimistic, how would you envision race relations in this country shaking out, say, 25 years from now? At your most optimistic.

CHUCK D: That’s when it’ll start.

RC: What do you mean?

CHUCK D: It’s going to take 25 years of hard work amongst ourselves to even get to that point. For us having an understanding of ourselves and our community, saying, well, we do well with you or without you. That’s the only time you respect somebody, when they say, I can do with you or without you. We got to get it going on. Usually, we’re just, Help me, can help me, sympathize with me, ‘cause we ain’t got it going on. I mean, be realistic. What we really need white people to do is just support us in our theories—just stay the fuck out of the way for a little while and if you’re going to do anything, just throw money and don’t ask for it back. It’s a hard thing to swallow, but, you know, you’ve got to understand. I’m in the middle of a tornado just as well as Greg. This is a mess that we didn’t start and we'‘e trying to find our way out of, you know what I’m saying?

RC: Do you think white people can help at all in this? Do you think that nothing we have to say—

CHUCK D: Throw some money.

RC: No ideas.

CHUCK D: No ideas. Money talks.

RC: So you’ve got no interest in reaching white people? It’s just incidental?

CHUCK D: My interest is reaching black people and whites who are good enough to listen and they want to fucking listen, fine.

RC: Do you think you can do them any good that’ll end up doing you good?

CHUCK D: They'll at least know our side and our perspective. Whether it’s the truth or not—

RC: It’s your perspective. And is that an important part of what you have to achieve here? ‘Cause after all, I mean—in your most optimistic projection, you see that it’ll take 25 years. And that’s assuming—

CHUCK D: Minimum.

RC: I understand. That seems realistic to me, at a minimum. But that’s assuming that the white people who still run this country and probably still will, certainly still will—

CHUCK D: Or their sons and daughters.

RC: Or their sons and daughters—will let you do it, won’t get in your way. And of course, they will get in your way, no question about that. The only question is how much.

CHUCK D: They can only get in one person’s way. They can’t get into fucking millions of people’s way. I’m a realist. I’m saying, we don’t get our act together this decade, it’s over. I’m not going to wait for that 25; I’m not going to wait for race relations. What’s going to happen, it’s going to be utter chaos 25 years from now. White people are going to be killed just like black people are getting killed. Senseless. Without mercy. It’s going to be like—it’s going to run rampant. You’re going to see more white mass murderers, more motherfuckers that qualify to be in asylums on the streets. You’re just going to see more madness. You can’t pile madness on top of madness, then it gets to a height where it gets totally crazy.

RC: Do you think there’s any way in which the success or failure of this project depends on what happens economically in this country? I mean, is it more likely to happen if some economic exploitation stops that doesn’t just apply to black people, it applies to white people as well? Do you have an economic vision that exists alongside the racial vision?

CHUCK D: I’m not an economist, so—

RC: You’re not a historian either.

CHUCK D: I’m not a historian and I’m not an expert on racial theory either. I think Dr. Welsing and the other people’ll tell you a lot better than myself about what my feelings . . . Of course it’s got to get better economically in order for this thing to come about. If it doesn’t get better economically, we have to figure out what we can do with what we got.

RC: Well, a certain portion of white racism comes out of economic resentment and fear.

CHUCK D: A great portion of it. But after everybody’s economically satisfied who knows what other racism—

RC: Damn right. No question.

CHUCK D: You’ll see shit coming out—motherfuckers want to be that way just ‘cause, fuck it, I just want to be this way. You know, it’s like with a lawn, right? You can have crabgrass, right? Cutting it ain’t going to do a damn thing—going to just grow back. It's got a fucking deep root, that motherfucker.

RC: And how do you do that?

CHUCK D: I’m not an economist. I know I’ve given a lot of ideas but you gotta say but this whole interview has just been my ideas. I could be right, I could be wrong.

TATE: I know what you’re getting to in terms of—you’re moving towards the whole idea of some kind of alliance, I guess, between—

RC: Obviously it’s what I think. But I really wasn’t moving towards anything—I really wanted to know what he thought.

CHUCK D: Economically between blacks and whites the only alliance that will happen will be black businesses and white businesses. That’s just like I do. I work with anybody, like the Mafia, man. Now, for—I’m not working for no one again. I tell companies right now, I’m in a business dispute with this particular company that I’m working, and I might say, no exclusivity on this end, I’m giving you exclusivity on this end—none. I know too much about slavery to be a slave again. I don’t care how much money you throw on the table. It’s just like—I’m not working for no one again.

9. P.S.

RC: OK. Enough. As far as I’m concerned. Is there anything else you want to ask?

TATE: Nothing.

CHUCK D: [To Greg.] I want to just apologize for that porch-nigger statement. I was mad. I can take criticism from anybody. But at that time, it was like I couldn’t see just getting criticized while I think I’m trying to do the right job, you know, in a white paper. I can get criticized all day long in the Sun, or Amsterdam News, or even on the block. I’m like, all right, I take my licks. But I felt like, damn, at least if I had talked face to face with homeboy, I could have explained it, being that he’s a brother.

RC: Think the Voice is after your ass? Do you still think that?

CHUCK D: No, I break it down to people, just like the Voice. RJ Smith—I don't like that motherfucker. I just don’t like him. Why? ‘Cause I just feel I don’t like him.

RC: You think he shouldn’t have reported that stuff that Griff said?

CHUCK D: Yeah. But as far—RJ Smith, it’s not so much that, it’s just, damn, we got a chance to get this nigger’s—

RC: That ain’t what happened.

CHUCK D: It’s a big story for me.

TATE: I mean, if he didn’t, listen, somebody else at the paper—

RC: I would’ve. Damn right I would’ve. What Griff said to David Mills was intolerable. Intolerable. And you gotta deal with it.

CHUCK D: I know, I deal with it. That was a situation where, you know, you have a nice guy running the ship, and expects everybody to do their fucking job correctly, no mistakes. And when the shit happens—you know, for different reasons, you’re like, damn, can’t a motherfucker do a job right? And that was that. I’m not going to do that ever again. I’m cutting the motherfucker off and watching the blood drip if they make a mistake. Look man, I built this house for everybody, the least thing you do is live in it and don’t fucking burn it down because you on some old tip, because you ain’t feeling love for a minute. That’s one thing I learned from that shit. Lead the ship and rule with a fucking firm grip. I told Flavor, man—they offered Flavor a St. Ides commercial, I said, Flavor, man, you take that shit, I’ll cut you off publicly so fucking bad.

RC: What’d Flav say?

CHUCK D: Flav still considered it. Said, Come on, you know me. I got a check and balance before any of that shit goes out.

TATE: Speaking of your responsibility, what about the Dee Barnes situation?

CHUCK D: That shit was foul. So I went out there not too long after that and I know Dre’s crew and all, ‘cause they worked with us on tour, and I was like, “How the fuck can y’all let this happen?” They was like, “Yo, Chuck, you know, he was drunk.” I said,

“Y’all fucking dumb.” That shit was foul, man. But my whole thing is like, I won’t get another brother in print—unless they come out in the media, or in the same print, and attack me.

RC: All right. There's one other question. Along with the Dee Barnes thing, seems to me I gotta also ask about the New York Post song and the incident with Flav. Do you think—

CHUCK D: They printed his address. That’s why I was mad. I tried to sue the Post. Tried to sue them. My lawyer told—

RC: Do you think that the incident itself wasn’t worthy of report?

CHUCK D: 'Cause you don't know the incident.

RC: Was he brought to jail?

CHUCK D: She kicked his ass. Look, his girl kicked his ass, he smacked her back, right? She didn’t call the police, she called the news station. From Channel 12 out here in Long Island, the Post took it.

RC: That’s your version of what happened with Flav?

CHUCK D: Yo, I wasn’t there.

RC: Flav's version of what happened with Flav?

CHUCK D: That’s people’s version that was there. He’s not big enough. She was beating his ass, you know what I’m saying? I mean, my whole thing is like this: there’s bigger and better news to be putting on there. Many of us rappers’ positions are being closely watched. And there’s people out there that realize that our words are meaning a lot, no matter who we might be. If I do the slightest thing—that’s why I say, all right, I’m grown and responsible. And adults make mistakes. But when you’re spotlighted—especially if you're black—they’ll take that mistake and they’ll fucking run with it. Just like, you know, a brother was telling me, it was this major-league sports team. This brother was a future perennial all-star, you know. They pinned drugs on him—and he never even took drugs in his life. But they pinned drugs on him so he couldn’t renegotiate his salary. They pinned drugs on him and then he was eventually just run right on out of the league. So it was like, OK, we’re spotlighting you, but the smallest amount of salt in the game will fuck you up. You know? They’re just waiting for Chuck D—

RC: I don’t deny that.

CHUCK D: Chuck D arrested for rape with a white woman. Public Enemy’s over with. It’s over with. It’s gone.