Storytellers

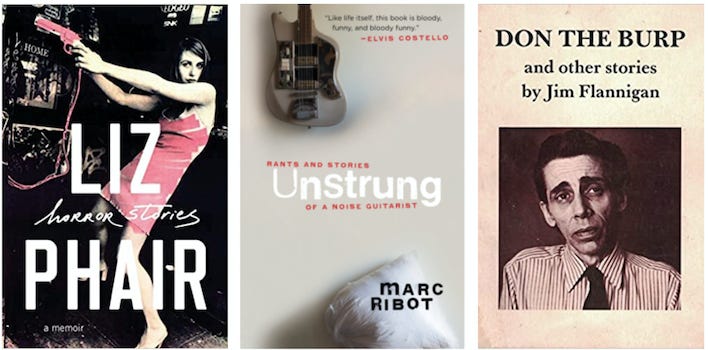

Liz Phair: "Horror Stories" (258 pp., 2019); Marc Ribot: "Unstrung: Rants and Stories of a Noise Guitarist" (216 pp., 2021); Jim Flannigan: "Don the Burp and Other Stories" (42 pp., 1980)

In part to further illuminate the eternal conundrum of just how autobiographical we can take first-person songs to be, I bought Liz Phair’s Horror Stories, a collection of autobiographical essays subtitled “A Memoir,” shortly after the iconic pop alt-rocker released Soberish, her first album of new material since 2010. Then, just as I was finishing it, Akashic Books sent me Unstrung: straight essays, memoiristic briefs, and other stuff by the irascible, idealistic avant-rock guitar dynamo Marc Ribot. And there on page 113 I was astonished to encounter, in the role of Ribot’s pot dealer, my unforgettable acquaintance Ray Dobbins, whose pseudonymous 1980 story collection I’d just devoured on the Q train to his wake at Roy Nathanson’s place. As I write there seem to be five copies of that one for sale, priced between $59.95 and $596.02 at Amazon and somewhat cheaper elsewhere.

Certainly Horror Stories is the star attraction, unexpectedly vaulting Phair to the top rank of rock litterateurs. That’s the right term, because I’m not claiming Phair’s prose compares with that of Dylan’s Chronicles or Smith’s Just Kids or Jay-Z’s Decoded or Springsteen’s Born to Run or for that matter Chuck Berry’s The Autobiography, all of which achieve a vernacularity congruent with their authors’ lyrics. Instead Phair’s ambitions as a page writer are basically literary, as in Carrie Brownstein’s Hunger Makes Me a Modern Girl or Donald Fagen’s Eminent Hipsters, admirable books that Horror Stories smokes stylistically. The praiseword I keep landing on is “immaculate.” From the first line—“We left her there. That’s the part that haunts me.”—to an impressively coherent death chapter that roams the passing of her grandmother, the aging of her parents, and fiftysomething intimations of her own, almost every sentence is clear, precise, well-situated, well-formed. Just as a prose fan I was not only impressed but drawn forward.

Thematically I found plenty to like as well, especially insofar as Phair addresses her stated project of “working so hard to become a better person.” That first line I cited refers to a girl sprawled face down on the ladies room floor, half in the stall and half out with “a big smear of excrement” visible between her legs as her upright sisters point and/or titter and/or get out of there quick. As Phair observes, this young woman isn’t merely dead drunk—she might literally be dying. Yet not a single partygoer including our 18-year-old protagonist dares give her a hand. It’s to Phair’s credit that she’s regretted it ever since, and that other chapters recount equally tiny moments—saved from spiders by her older brother at 12, comforting a surgery-bound young stranger after a high school party, felled by a bloody nose at a college reunion, minding her young son at the Lake Michigan dunes. In addition there’s a gripping not to say harrowing description of a 36-hour childbirth, a detailed account of a love affair with a liar, the announcement that “my soul resides in my pussy; in my clitoris, to be exact,” and a passage I found of special interest as an adoptive parent because she and her brother are adoptees: “For as long as I can remember, I’ve pondered the existential questions of who I am and where I came from. The specter of abandonment has waited in the wings, lurking in the shadows, insisting on acknowledgment.”

Yet at the same time I found myself put off by the cultural markers Phair lays down. Looming large among the many female artists who pushed ‘90s rock toward gender parity, Phair came out of Chicago’s Wicker Park scene to score the breakthrough Exile in Guyville at the alt-rock citadel Matador, but Steve Albini wasn’t just being the sexist elitist he is when he dismissed her as “a rich suburban girl” with an “incredibly aggressive marketing campaign.” While many alt-rock notables grew up in the tonier precincts of suburbia, the composer of “Shitloads of Money” makes clear that from childhood in Winnetka to parenthood in Lincoln-not-Wicker Park to maturity in Manhattan Beach, suburbia has always been her natural home. It’s one thing to read about the manifestly fantastic superstar lifestyles of Elvis or Aretha or Madonna—their world is one thing, us mortal folks’ another. But lesser stars like Phair are basically a species of successful professional, more famous than most for sure but not necessarily more affluent—or less bohemian. Phair is candid and sane about enjoying the glamour, recognition, perks, and income stream of her midlevel celebrity—and also about how disorienting it can still be sometimes. I liked and understood the craftily allusive Soberish better after reading her book. But though classwise I’m situated somewhere between her and Marc Ribot, getting his Unstrung in the mail was a relief. My people!

This is partly because we’re both New Yorkers and partly because we both identify left although he’s less electorally inclined than I am—for all its reflections on morality, Horror Stories barely mentions politics. Then again, Unstrung doesn’t really either—although reference is made to Ribot’s longstanding tenant activism and battles against musical Googlization, it would be misleading to claim that any of these 43 pieces, most previously unpublished and only two even 10 pages long, addresses either topic directly. In literature as in music, addressing topics directly isn’t Ribot’s way, although yes he’s recorded a whole album of protest songs and yes his farewells to guitar brother Robert Quine and compilation maestro Hal Willner come close enough. As a sideman—with Tom Waits, Elvis Costello, Marianne Faithfull, Yoko Ono, Arto Lindsay, James Carter, Susana Baca, the Jazz Passengers, and his musical soulmate John Zorn, among countless others—he’s always aimed to be direct and disruptive simultaneously, and the same goes for his writing. Immaculate is not in him.

Unresolved or not, I found most of his autobiographical material redolently factual, which is to say interesting. Learning guitar from Haitian friend-of-the-family Frantz Casseus or dismantling his daughter’s Ikea loft bed after she’s moved out, telling fragmentary tales of what it’s like to pursue your muse in northern Maine before you can use a pick or tour European metropolises alone—all this is unique and well-rendered, as are his economically detailed impressions of varied moments in varied lowish-rent NYC bohemias. Where the collection falls apart for me is in its more literary sectors—the nine brief “film (mis)treatments” (his term) and 11 fragged fictions (mine) that occupy the book’s final third. Although I’m a guy who regularly marks books up in pencil, on these pages I did so only twice—to single out the all too revealing (and dubious) “an ambivalence about compromise with the world that any realization of art entails” and to add a “nu” to one called “Dialogue of the Sushi Eaters.” “Bloody, funny, and bloody funny,” saith Elvis Costello of these trifles. I just say nu.

And then there’s Ribot’s pot dealer Ray, who given their Roy Nathanson connection I thought might be the recently deceased Dobbins even before Ribot had identified him as a Jesuit-educated gay man from Cleveland. That was Ray Dobbins for sure, and though I’d seen him barely at all in this century he was on my mind. Ray and Roy were a couple I’d met in 1970 at the Astoria Collective my pal Tom Smucker was part of. Roy was a saxophonist who backed the Shirelles for years before first joining the Lounge Lizards and then forming the Jazz Passengers and marrying a woman. Ray was merely the finest storyteller I’d ever met, an endlessly garrulous guy who combined the best aspects of a conscientious objector turned nurse and an Irish barfly after one too many. His flow was so humane, detailed, and funny that I eventually tried to get him to write features for the Voice—to no avail, he just couldn’t put the words on paper, though he did manage one about Roy’s travails as a wedding musician and much later contributed lyrics to Roy’s Fire at Keaton’s Bar & Grill. It was Ray who first turned me onto fellow Clevelander Harvey Pekar, which resulted in Voice Pekar features by first Carola Dibbell and then Marshall Berman that helped spark David Letterman into making Pekar a famously grumpy star. Together with Pekar’s widow, Joyce Brabner, Ray eventually pitched in on a Lambda Prize-winning graphic novel about Ray and pals smuggling AIDS drugs into the U.S. in the early days of that plague.

Long before Brabner or I got involved, however, another now- deceased Astoria Collective associate, Jon Ende, had taken the bullshitter by the horns by secretly taping and transcribing some of Ray’s tales and then—with Ray’s editorial and also graphic cooperation, photography being another of his skills—self-publishing them under the pseudonym Jim Flannigan in a glossy seven-by-nine-and-a-half chapbook just 42 pages long. Don the Burp and Other Stories collects eight explicit, subtle tales about growing up on Cleveland’s West Side, working at a hillbilly hamburger joint called Lawson’s, and gradually figuring out that, unlike most of the guys you know who are involved in an underground favor bank of blow jobs, massages, and pills, you’re actually gay. Most of these fellas are fundamentally decent no matter how far behind the eight ball, though a few are sexist assholes; both female characters, with one of whom “Jim” briefly tries his hand at romance, are smart, strong, and sympathetic. There’s no romanticization of the working-class male that I can discern, but plenty of respect—as long as women don’t get misused. The laughs were less plentiful than I recalled, although the title story, which is also the finale, is wry in a disorienting way. Humane, however, these tales definitely are. Phair and Ribot should only project such generosity. Me too.

Ray, who spent most of his life way overweight and had many other health problems, died peacefully a few months ago. But putting the memorial service together took a while for Roy and his wife, who told those in attendance that she’d solved the tricky problem of how to relate to her husband’s ex-lover by treating him as if he was her mother-in-law, exchanging recipes and complaining about hubby’s faults. I didn’t know many of the mourners, most of them gay men. A few of them, I gathered, have arranged to place Ray’s archives with NYU, so maybe we can hope that Don the Burp and Other Stories will enjoy some kind of second life. But I was struck as well by how well-represented Ray’s Irish Catholic family was. Two carfuls from Cleveland, it looked like to me, all of whom seemed proud that Ray was one of their own. Both of his parents, we were told, were cops. I bet they could have told some stories of their own.