Steely Dan's Long Strange Trip

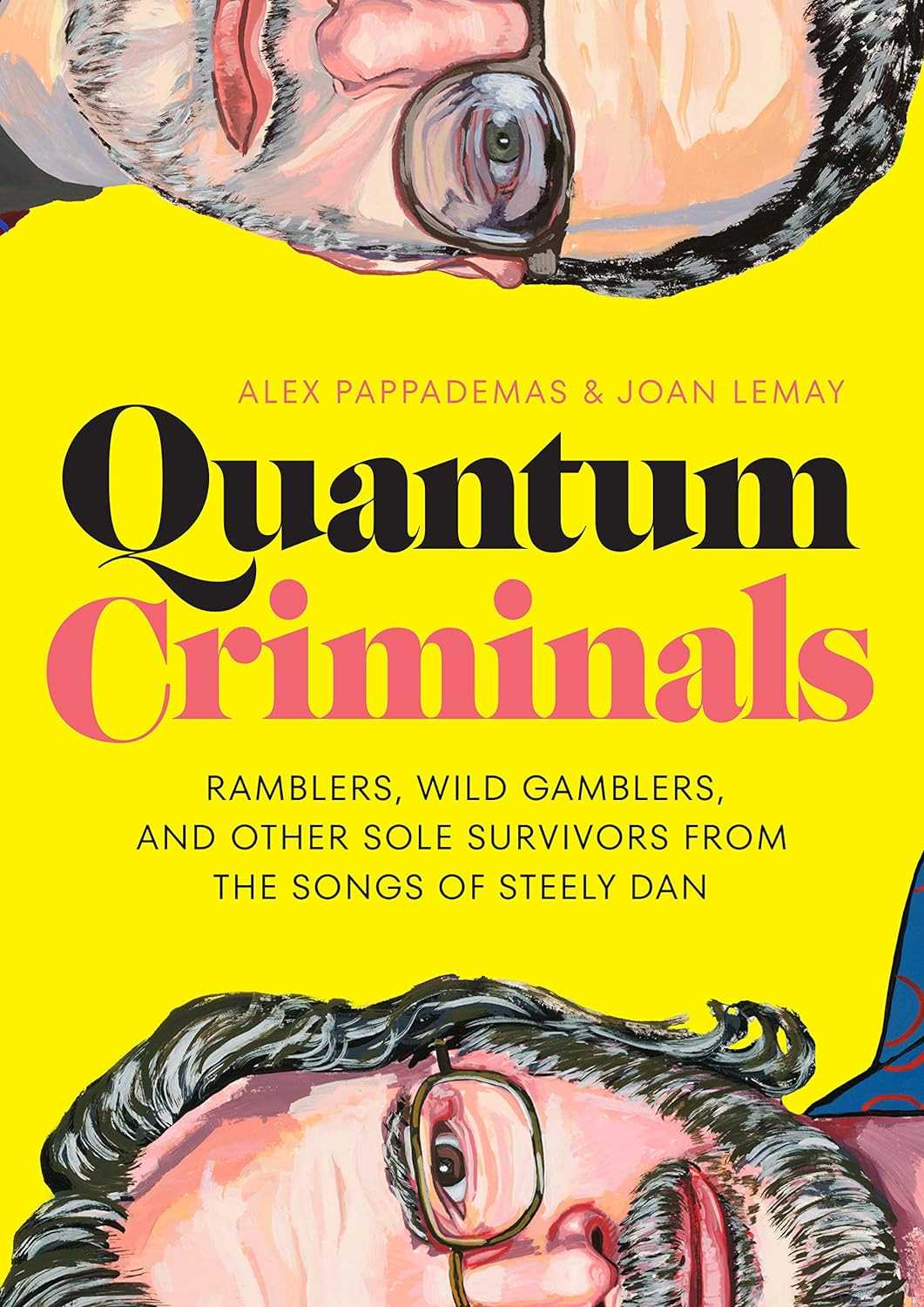

Alex Pappademas and Joan LeMay, "Quantum Criminals: Ramblers, Wild Gamblers, and Other Sole Survivors From the Songs of Steely Dan" (2023, 268 pp.)

So I’m driving uptown on a winter night in 1973 with my honey beside me and WABC blaring the hits. Sometime in there I recognize a songlet already imprinted on my auriculum—rumba‑lite drum part beneath a repeated guitar riff that soon flowers into a catchy guitar hook perfectly suited to a repeated snatch of title verbiage that goes “You go back, Jack, do it again.” About a month post‑release and already I recognize “Do It Again,” the rare hit with some intellection to it: a compelling lyric about compulsive behavior with an aptly addictive musical allure of its own. Smart. Dark. Double‑edged. Which as the fledgling rock critic of Long Island’s Newsday it’s my nice work to notice. I’ve been mailed an album by this Steely Dan group, so I put Can’t Buy a Thrill on at breakfast and Carola likes it a lot. For several years Steely Dan will flavor many of our mornings.

It was a while before I got the band into Newsday—a March 1973 Westbury Music Fair gig opening for Cheech & Chong just didn’t make the cut. But that show did render me one of the rarer members of what I can’t just call the Steely Dan cult because their fanbase has gotten way too big by now and I’m not really part of it anymore anyway: not only did I see them live when their lead singer was bland blond nonentity David Palmer, but a year later Carola and I met Donald Fagen and Walter Becker in producer Gary Katz’s hotel room. Smart guys they certainly were, and you bet I covered the headlining Westbury gig they were in town for. But though I still remember how high they rated Wayne Shorter‑period Miles, I also recall that they weren’t altogether amused when I dubbed them “the Grateful Dead of bad vibes,” which might have been a nice hook to hang a Q&A that never happened on.

By then Steely Dan had already gone public with album number three, Pretzel Logic, which became our favorite at least in part because it historicized the band’s fondness for jazz. To “Parker’s Band” and its Bird‑calling “Savoy sides presents a new saxophone sensation” it added Duke Ellington’s near‑comic 1926 instrumental “East St. Louis Toodle‑oo” and led off with their biggest hit single, “Rikki Don’t Lose That Number,” which owed a blatant but never‑paid melodic debt to Horace Silver’s “Song to My Father.” At a time when Blood Sweat & Tears were still the ultimate in jazzed‑up rock, Pretzel Logic was number one on my 1974 Dean’s List, ahead of Dylan and the Dolls even, and finished second Pazz & Jop. We dug 1975’s Katy Lied too, judging it superior to 1976’s equally well‑received The Royal Scam. That’s five albums in five years, four in a row top 10 Pazz & Jop with the big one to follow: 1977’s Aja, about which my review began “Carola suggests that by now they realize they'll never get out of El Lay, so they’ve elected to sing in their chains like the sea.” In the pivotal year of Never Mind the Bollocks, Marquee Moon, Rumours, and My Aim Is True, Aja finished only fifth Pazz & Jop. But over the years it became a widely acknowledged all‑time classic, archetypal Steely Dan—the album where their increasingly obsessive perfectionism is served up in delicious bites to the millions of fans who adore this obsessive pair and also to the structurally interchangeable L.A. studio virtuosos eager to do their captious bidding.

Despite its parallels in the carefully constructed track‑and‑hook aesthetic of pop producers typified by Sweden’s Max Martin, endlessly tailored studio perfectionism isn’t my idea of how pop music best comes to be. I prefer things a little looser—both more human and more humane. True, the aesthetic Aja and its offspring epitomize cultivates error in its own perverse ways—perverse not least because it’s so perfectionistic about how precisely and subtly it identifies, examines, tailors, and fetishizes accident and oddity. But give me a batch of catchy songs with some intellection to them and I’ll settle.

This brain‑teaser isn’t something I’d given much thought recently until I was mailed the true subject at hand here: Alex Pappademas and Joan LeMay’s high‑IQ picture book Quantum Criminals: Ramblers, Wild Gamblers, and Other Sole Survivors From the Songs of Steely Dan. That’s because I pretty much stopped thinking about Steely Dan post‑Aja, not so much because their focus had shifted from brainy songwriting to brainier production but because when punk generated “new wave” the competition got a lot stiffer in the brains department. Hip‑hop was in the wings too, just beginning to evolve its own varied species of intellection, and there too stood King Sunny Ade opening the door to the Afropop I’ve found stimulating, sustaining, and educational ever since. So for decades the most‑played Dan album around here has been Donald Fagen’s 1982 The Nightfly, which Carola prizes for its JFK‑era nostalgia—the early ‘60s as a time of promise not protest. “We’ll be eternally free yes and eternally young,” Fagen—imagining a jazz‑lite hipster DJ so much cooler and hipper than the acid‑addled “hippies” to come—assures us imperturbably in his solo album’s Grammy‑nominated opener “I.G.Y.” This glimmer of liberation is only a dream, of course. But the dream inspired a pop song that stayed in the top 40 for a month.

None of which is to even suggest that Aja didn’t leave a more pungent spoor. Fact is, it wound up apotheosizing a cult—a cult so huge and proactive that by the time I was through reading Quantum Criminals, a pleasurable enough task, I was wondering why no one else had written a Steely Dan book. Soon, however, I learned that many had, so many that in November 2021, essayist Colin Marshall published a sharp, lengthy Los Angeles Review of Books piece called “Born Middle‑Aged: Eight Books on Steely Dan”: Brian Sweet’s 1994 Steely Dan: Reelin’ in the Years, Dan Breithaupt’s 2007 33 1/3 Aja, Donald Fagen’s own 2013 memoir plus essay anthology Eminent Hipsters, Anthony Robustelli’s 2017 Steely Dan FAQ: All That’s Left to Know About This Elusive Band, Barney Hoskyns’s 2018 Major Dudes: A Steely Dan Companion, Jez Rowden’s 2019 Steely Dan: Every Album, Every Song, Brian Thornton’s 2019 Die Behind the Wheel: Crime Fiction Inspired by the Music of Steely Dan, and Brian Thornton’s 2019 A Beast Without a Name: Crime Fiction Inspired by the Music of Steely Dan. Quantum Criminals obviously belongs in this canon. In fact, it almost certainly deserves placement near if not at its very top.

Except for Eminent Hipsters, a review of which is included in my Book Reports anthology, I haven’t even laid eyes on any of the others and feel no special urge to start now. So it’s possible Quantum Criminals is a less decisive winner than I believe. But I doubt it, for two salient reasons. First, it’s big and luxurious physically, a little over seven‑by‑ten, just barely crammable into a largish normal bookshelf. Second, it’s illustrated big‑time, with each of the 50 chapters it spreads over 248 pages devoting at least half a page (with 42 full‑page) to one or more of painter-illustrator LeMay’s quasi‑realistic caricatures. Hence it’s a book both handsome and playful, with an idiosyncratic look that has the effect of suggesting that maybe these hyperintellectual musical powerhouses, down to just Fagen and hirelings after Becker died of esophagal cancer in 2017, were so ironic that not taking them at face value, whetever that could even mean, was the only way to achieve maximum comprehension. Without question Steely Dan has now played a major and perhaps even decisive role in Pappademas’s career as a rock critic. No more important than the wife and child whose emotional sustenance pointedly nourishes a closing chapter called “Daddy.” But not necessarily that much less either.

So in “an age when a grasp of ontological slipperiness became prerequisite for decoding pop culture”—examples: “Rick Ross, the Weeknd, Tyler the Creator, Fox News, Tony Soprano, and Donald Trump”—Pappademas spent what may have been years pondering “two grumpy‑looking guys obsessed with making the smoothest music of all time” while specializing lyrically in “monied decadence, druggy disconnection, slow‑motion apocalypse, and self‑destructive escapism.” “They wanted songs to sound a certain way, and pursued that fidelity at the expense of the spontaneity and friction essential to the part of rock that’s derived from rock‑‘n’‑roll,” “never wrote a song containing one iota of political idealism,” and—as Rickie Lee Jones once put it—seemed “obsessed with women they did not really like.” Pappademas is such a hell of a critic that I can’t resist quoting his take on my beloved Thelonious Monk, who “played with his right and left hands in different dimensions and made the piano sound like broken china sutured together with gold,” or appropriating his full list of penis bands after establishing that Steely Dan itself was named after a dildo fabricated by William Seward Burroughs III: “Jelly Roll Morton, Tower of Power, Throbbing Gristle, The Sex Pistols, the Meat Puppets, Whitesnake, Helmet, Tool, Mushroomhead, Swollen Members, Velvet Revolver, and Third Eye Blind.” And I accept Pappademas’s deep emotional attachment to Steely Dan, plainly a source of equilibrium for him in an age whose ontological slipperiness imperils anyone who has a heart. But as an 81‑year‑old who was a Dan fan from the very beginning, I reserve the right to wish that very smart guy Donald Fagen was mature enough to scare up sufficient spontaneity and friction to power some small battle against the ontological slipperiness that’s come to imperil us all.