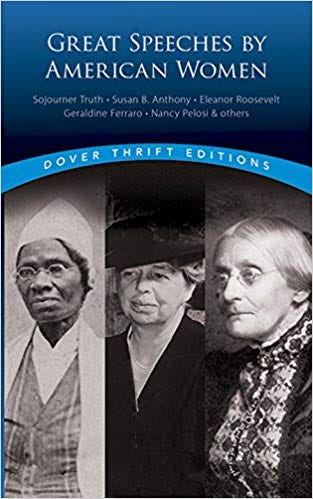

Having taken just one history course since high school, I may be more excited about this book than my juniors might be. While I’ve read unsystematically in and around feminism since I was given a copy of The Second Sex in 1965, the nearest I’ve come to history is Alice Echols’s Daring to Be Bad, which begins in 1968 and ends in 1972. By now, I hope, the women’s rights details I caught up on via this collection are part of the standard college history curriculum. But having laid down five bucks for it at the modestly mind-blowing Women’s Rights National Park in Seneca Falls, New York, I found myself equally mind-blown by its chronological selection of 21 speeches ranging from two to 22 pages, with the longer ones front-loaded because oratory was public entertainment in the 19th century.

Most of these older selections proved spellbinding for me. I was well-versed enough to recognize the names from Sojourner Truth to Jane Addams. But it was bracing and even shocking to encounter not just the eloquence of their voices but the details of the oppression they were combating: the absurdities, indignities, injustices, and outrages, as regards property and employment law as well as political rights, to which all of these brave and brilliant human beings bear witness. Twice they feel compelled to enlighten all-male audiences of legislators so sexist they need to be schooled about malefactions committed in front of their faces—often, bet on it, by themselves.

In 1854 Lucretia Mott catalogues endless evildoing in a lecture to the 5th National Women’s Rights Convention titled simply “Why Should Not Woman Seek to Be a Reformer.” In 1880 Susan B. Anthony explains to the Senate Judiciary Committee that it should pass a women’s suffrage amendment on the simple ground that cruder men reject it, dropping in similar arguments for the temperance movement that was also her passion. In 1892 Elizabeth Cady Stanton tells the same committee that women deserve rights equal to men’s because women are even more beset than men by “the immeasurable solitude of self”: “Alone she goes to the gates of death to give birth to every man that is born into the world.” In 1893 Lucy Stone, the first American woman to decline her husband’s surname, outlines half a century of women’s progress to the Chicago World’s Fair’s Congress of Women. The daring anti-lynching journalist Ida Wells-Barnett cites example after example of black men murdered by mobs of white men for the unspeakable crime of letting white women love them. Settlement house godmother Jane Addams delivers an astonishing critical essay comparing the bloody Pullman strike of 1894 to King Lear.

The 20th century material is less consistent: pols Margaret Chase Smith, Geraldine Ferraro, and, sadly, Nancy Pelosi fail to distinguish themselves, although Hillary Clinton is fine on the 2006 reauthorization of the Voting Rights Act she couldn’t know the Roberts court would gut in 2013 and you have to love the way salty left-populist Ann Richards rams home a 1988 Democratic convention keynote that begins: “After listening to George Bush all these years I figured you need to know what a real Texas accent sounds like.” But more than compensating are two longer selections I expected less from because they were by, well, celebrity feminists: Gloria Steinem and Jane Fonda.

About Steinem I should have known better. She’s always been an ace journalist who knows how to put words together, here by sketching “A 21st Century Feminism” that rather than standing “on the bank of the river, rescuing people from drowning” works to replace a “patriarchal-nationalist” system that “going on in various stages between five and eight thousand years” has proved “a failed experiment.” But Fonda deploys no less adventurous and commanding a mind as she schools a 2004 conference her daughter had scoffed was “so New Age” in unapologetically New Age terms: “the empathy gene is plucked from their hearts,” “we have to become the change that we seek,” “she moved from a place of love,” “empathic government,” “Eve, life, consciousness.” Men, she charges, are “emotionally illiterate.” But she cites her “favorite ex-husband Ted Turner” nonetheless: “Men, we had our chance and we blew it. We have to turn it over to women now.”

Sixteen years later, of course, that hasn’t happened. Instead we have every right to fear that we stand on the cusp of a sexist reaction that will wreck the planet and what was once called mankind along with it. But this book stands as a reminder that for going on two centuries, wise, brave women have been struggling to insure that the human race survives.