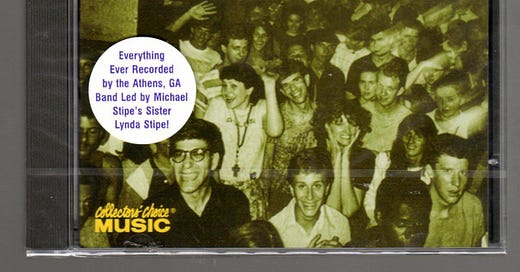

As Rob Sheffield and I discussed on the Auriculum podcast that went up yesterday, Oh-OK’s minuscule catalogue is commercially available again—though also going fast and also, to be sure, streamable—as The Complete Reissue. It comprises 17 songs where the long out-of-print 2002 CD dubbed The Complete Recordings somehow comprises 23. The CD was sequenced so the Athens band’s two legendary EPs occupy the first 10 tracks that lead into 13 live tracks; on the vinyl, four EP tracks are followed by five of the same live tracks before six EP tracks are followed by another two. There’s a sense in which this is a good idea, because the EPs are so legendary that the CD’s live stuff is experienced as a dropoff that’s less pronounced on the vinyl, in part because the material the compilers single out tends more finished and a closer match sonically—no male voices, for one thing. As a result the vinyl homes in more on the distinctly girlish voices of Lynda Stipe and Linda Hopper, who were in fact 19 and 22 when they convened in Athens G-A in 1981 but, crucially, sounded much younger. For further elucidation, I recommend the CD’s liner notes, written by Robert Christgau and Carola Dibbell, our most auspicious collaboration primarily on the strength of Carola’s insights. Details get misty 20 years on, but figure I provide the biz context, which does the job, and Carola most of the many aesthetic apercus, which both sparkle and giggle. Here those liner notes are.

The legacy of Oh-OK is tiny in every way. In a “career” that lasted from 1981 to 1984 they released all of two long-lost EPs, one a seven-inch—10 songs that totaled under 22 minutes. Essentially they comprised two members, writer-bassist Lynda Stipe and singer Linda Hopper; not only is it hard to remember the names of their two (quiet, male) drummers (David Pierce, David McNair), it’s hard to remember that on their second record they were joined by guitarist Matthew Sweet, who later became something like a star. Oh-OK liked toy instruments, small topics, rudimentary tunes. Yet after spending the CD era up on the shelf, their music doesn’t just sound utterly original, as it always did. It sounds momentous.

Before you get the wrong idea, let’s clear up a few things that Oh-OK were not. They weren’t punk, they weren’t camp, and even with Sweet strumming along they weren’t jangle-pop. Rather, in a world where all of these modes were creating much musical hubbub—Athens, Georgia, already home of the B-52’s and Lynda’s brother’s band, R.E.M.—they related recognizably to all three categories yet didn’t come near to fitting any of them. If they owed any Athens band, it was Pylon, who presaged Stipe's supple, angular, hooky bass. But alone with a simple drum kit and two blatantly feminine voices, the effect was both more awkward and more bold, like a crayon drawing.

Blatantly, but not conventionally—their small vocals were less what is called pretty than direct, savvy, fun-loving, and self-possessed. As their greatest song put it, in terms that spoke just as loudly to two-year-olds as to forty-year-olds (we checked): “I am a person, and that is enough.” At a time when every female who walked on stage signified some wonderful solution, Oh-OK signified walking on stage—unanorexic and giggly, wearing dresses, ribbons, and fluffy hairdos rather than costumes or tomboy rock and roll uniforms. It seemed as if they were so inexperienced they hadn’t had time to harden. Yet their voices weren’t as small as all that—they projected. More important, what the voices projected was a realized, if brief and suitably DIY, body of work.

The standard view among the small cadre of Oh-OK scholars is that the four songs on the seven-minute seven-inch, Wow Mini Album, are classic in their minimalist purity, while the six songs on the fourteen-minute twelve-inch, Furthermore What, were somehow compromised by that old rock and roll inevitability, maturity, not to mention Sweet’s incipient mastery of the power pop palette. But two decades later, put together on a CD that admittedly sounds bigger at track five, all ten songs—plus the 1982 live track “Random,” released in 1990 on DB Records’ Georgia comp Squares Blot Out the Sun—are of a piece. The melodies are hauntingly simple, their straightforwardly appositional two-part structures often tricked up with funny little sounds; the guileless voices skip through lyrics that make a point of delivering reassuringly familiar language or details, a touch of the everyday. But for all their sturdiness and fun, the songs are also contemplative, dreamy, a little spooky, the tunes like nightmare sequences from ‘50s movies, or ancient rounds, or the two-note chants a kid might make up to explain the puzzling rules of life.

Once again we don’t want to give the wrong impression, because we don’t think Oh-OK were really cute either. But for sure they mined the childlike. It isn’t just the direct quotes from “One Two Buckle My Shoe” and “Red Rover” and the imagery copied off kiddie wallpaper (“The old west really looked like that,” claims “Giddy Up”). It isn’t just the voices, or the way the band’s particular incomprehensibilities (“had I not gone I would have never . . . known? met? meant?” or “he is for an expandy [huh?] . . . hole? home? hoe? can’t be ‘ho”) evoke the drawl parents everywhere know means nap time. It’s the whole way these youngsters, who were 16 and 18 when they began, related to the Athens scene, which in its own beginnings was uncommonly idyllic—into play, not dark. But it wasn’t shallow. As their name announced, R.E.M.’s depth move was the dream song, which Lynda dabbled in on “Choukoutien.” But in general she approached the secrets of the subconscious by the more direct, literal route of childhood memories and polymorphic childhood consciousness. Beneath the simplicity was mystery, full of delight and touched with dread. Oh-OK were happy even though they knew there were scary things in the big woods. They found the world more interesting that way. They said why and it sounded like wow.