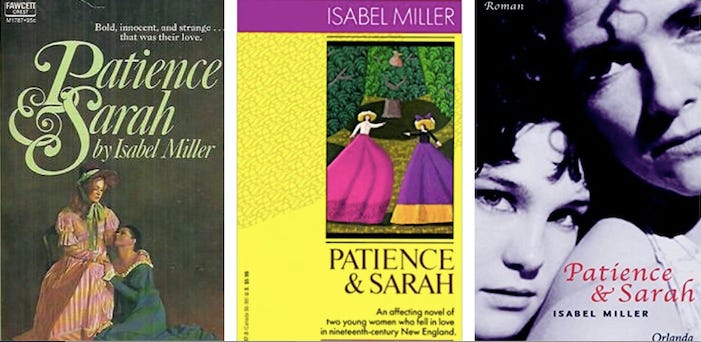

Trawling our bookshelves in search of an enjoyable novel that wasn’t too long or too light—Furst? Forster? Colette?—I came across a diminutive $1.50 Fawcett Crest paperback I’d never noticed: Patience and Sarah by Isabel Miller, cover illo two women in long 19th-century dresses with the anachronistically bare-shouldered brunette kneeling at the other’s feet. So I asked my wife, who instantly recalled reading it back in our early days—copyrighted 1969 as A Place for Us, the retitled edition is dated 1973. To my surprise she gave me a quick, enthusiastic OK. Knows me well, does my wife.

I loved this book, swallowed its 184 pages of text in under 48 hours, and though my Fawcett version would appear to be gone gone gone, a plethora of other editions is available from varying sources at widely varying prices. Amazon lists a new paperback of one such at $920.99, but you can find the novel far cheaper and even very cheap; Abebooks has 45 available as I write; if audiobooks get you going, you poor lost soul, there’s one featuring Janis Ian and Jean Smart that garnered a Grammy nomination, which reminds me to mention that in 1998 an opera version was staged and way back in 1971 the American Library Association is said to have created the Stonewall Award for this book. I mean, talk about a cult classic. Go to Goodreads, that often dismaying glimpse of everyday literary pleasures, and grok quickly how beloved it remains.

Patience and Sarah is a love story that flowers between 1816 and 1818 in eastern Connecticut’s Housatonic Valley and comes to full fruition when the two women buy a farm in Greene County in the northern Catskills. Patience is older and, thanks to her father’s providential will and testament, independently wealthy enough to set off with her beloved and buy a modest homestead; Sarah grew up in a much larger and poorer family where an endless parade of female children compelled her to literally wear the pants as her father’s right-hand man. They meet when Sarah delivers some wood one winter day and less than a week later are making out in the separate apartment Patience owns in a wing of the well-appointed family house. In a world where Sarah’s pants alone render her what Patience’s mean sister-in-law calls a “freak,” this is hot stuff. And sexy parts continue to spike a plausible, action-packed tale often described as “meticulously researched.”

I don’t know about that. Insofar as Patience and Sarah is a historical novel, it may or may not be true. Certainly one of its pleasures for me was familiarizing myself with the pasts of two northeastern regions I’ve often visited or passed through, particularly Greene County, where my sister has a summer place in a region where farming continues as well. I was also taken with the 25 pages the couple spend in a vividly rendered early Manhattan, where I know the historiography better. But although the principals are based on a documented couple who shared a Greene Country farm from 1810 to 1825, the relevant research couldn’t very well be meticulous because there’s little else there. Patience is based on the primitivist painter Mary Ann Willson, whose scant surviving work resurfaced in 1943 and who is said to have resettled in Greene County from Connecticut in 1810 with a Miss Brundage, no given name immediately apparent although newer accounts call her Florence. There Willson painted and Brundage farmed until Brundage died of unspecified causes in 1825, whereupon a heartbroken Willson disappeared from view.

Presumably painter Willson came from more wealth than farmer Brundage, but beyond that Miller is obliged to imagine the two Connecticut families who populate half her tale, with the other half devoted not just to the couple’s Greene County resettlement but to the many months Sarah spends fending for herself on the road after the two families try to separate the couple, mostly by helping out a traveling bookseller. This man who thinks she’s a boy that he’s taught to read is dismayed but philosophical when he makes a pass at the fellow and learns she’s not actually a fellow—though he himself, mind, has a wife and family in Manhattan, where later he’ll welcome Sarah and Patience on their way upstate together. As a lesbian couple in a frontier America with little or no conception of such a thing, the two women never come out except eventually to their families. But the uncommon kindness they encounter makes it seem that Isabel Miller was set on creating an idyll that did poetic justice to a gay rights movement just coming into flower as she conceived her tale.

Her mother a nurse, her father a police officer, Miller was born Alma Routsong in Traverse City, Michigan in 1924. At 22 she married a man with whom she bore four daughters while also publishing two novels devoid of lesbian content. But Patience and Sarah, written under a pseudonym that combined an anagram for “Lesbia” with her mother’s maiden name, was stonewalled by the industry, so she put it out herself with her longtime lover, economist Elisabeth Deran. Who knows to what extent if any that relationship inflected the Patience-and-Sarah relationship she invents. Her heroines are much younger and less worldly, but the intensity with which they crave and enjoy each other’s company—and also, as that becomes more of a given, the nervous, alienated moments that undermine or compromise that intensity—certainly evoke ups and downs I’ve experienced. As a monogamous romantic I found myself both touched and mildly aroused by how much they like to kiss each other, which Miller conveys as much with pace and tone as with concrete detail. Before long it becomes clear that breasts are also involved, and eventually you learn that they even have a way to say “orgasm,” a term then decades in the future—“my melt,” they call it, which I say is about perfect. Clearly one reason readers love this book is that it's sexy without being pornographic.

Patience and Sarah is narrated by its protagonists, who trade off over six sections. Having only learned to read after she met Patience, Sarah’s style is somewhat plainer than Patience’s, but since the entire tale is retrospective Miller doesn’t overdo the distinction—the two voices share an unpretentious, unliterary concreteness that pervades a novel with its own nice approach to realism. Sarah-disguised-as-a-boy imagining stealing kisses from girls she might meet: “A kiss that you feel deep tears you deep later when it’s lost. But a laughy kiss hurries you on your way and makes the miles fly.” Patience as the two women get settled on a steamer to New York: “The captain is chanting again, recovered from the flurry of our arrival. The crewmen with many curses are loading horses. I do see we mustn’t go outside while men are cursing.” Together the two voices fuse into one almost unnoticed style that delights as it informs. Village Voice reviewer Bell Gale Chevigny may be overdoing it: “The writing has the directness and whimsicality of primitive paintings—it is like spiked gingerbread or surprising samplers. The tone is sweetly bold. And the tale evokes many kinds of frontier at once.” But how evocatively the story describes and how easily it moves is proof of Miller's writerly subtlety and has to be another reason her novel is beloved.

History tells us that death stole one lover and devastated her survivor. But we leave their fictional counterparts as they’re struggling alongside their just-built bedstead—“a shaggy rectangular frame on shaggy cornerposts”—to fashion a mattress worthy of “the bridal sheets of fine linen” from Patience’s hope chest. They’d looked forward to a “feast,” “wild and careless and noisy and free.” Instead, the mattress is a mess and all they get is one very soft, very long kiss plus Sarah's resigned observation that “You can’t tell a gift how to come.” Which for that night, at least, is enough. After all, they still share a future that they and the reader can believe will be happy if hardly trouble-free. And I believe this is one more reason Miller’s novel is beloved—probably the most compelling reason of all.