Just Enough Monkey Business

"Our Great National Parks," Sophie Todd (series producer), Barack Obama (executive producer, narrator)

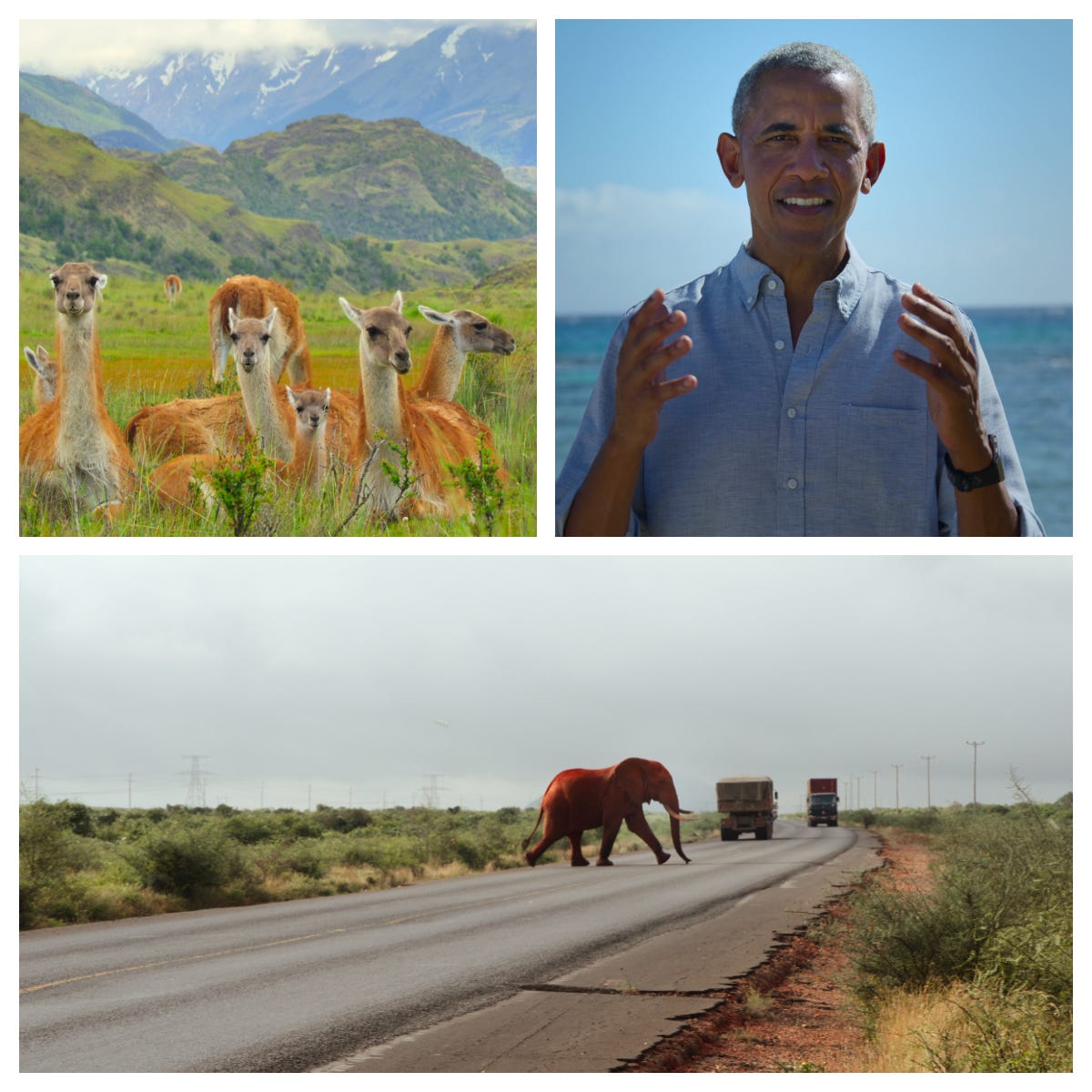

Let me mention Yellowstone up top to honor not Kevin Costner, whose TV series of that name I’ve never laid eyes on, but Ulysses S. Grant, who as a better president than you think chartered Yellowstone as the world’s first national park just 150 years ago. Good idea, savior of our so-called union, because there are now four thousand such parks, sanctuaries, and refuges worldwide. And although one of the five episodes of Netflix’s glorious Barack Obama-narrated Our Great National Parks, four of them directed by women, homes in on the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, which after decades of DC back-and-forth finally got the official green light in 1992, the series barely brushes by other U.S. projects. Instead it takes viewers on hour-long trips to Patagonia, Kenya, and Indonesia—the last two of which, as it happens, have a claim on narrator Obama, Kenya as his father’s birthplace and Indonesia as one of his boyhood homes.

Obama’s narration in this series has inspired comparisons to nature-doc champ David Attenborough and been nominated for an Emmy, and though it’s my guess that he farmed the script out, I also assume he had plenty of input—the man’s always been a writer. On an up-and-coming orangutan known as Rakus: “His name, given to him by resident scientists, means ‘greedy,’ because he likes to eat pretty much everything. Leaves, bark, fruit, termites—it’s all on the menu.” That “all on the menu” is Obama’s kind of colloquial touch. So of course the series’s climactic finish bears his casually moralistic stamp: “National parks are one of our greatest achievements. Over time, we’ve created nearly a quarter of a million protected spaces in nearly every country on earth. But in this world that’s getting warmer and more crowded, we have to do more.”

For sure few culture consumers will take in these five one-hour films just to hear a world-class orator strut his stuff. On an enormously ambitious project that has to be seen to be believed or even comprehended, Obama is a cross between a promotional booster shot and the icing on the cake. It’s the images themselves that will rock your world. Surfing hippopotamuses? This does actually happen, and yes, it does truly look like these pachyderms are having what can only be called fun catching waves. Famously solitary pumas in chilly Chilean Patagonia make nice not just to other pumas but to humans. Shy sloths host as yet unexcavated microcosms of potentially medicinal bacteria in their long coats. And that’s just a few subtleties in a series that tracks plenty of bigger game. Hippos don’t just surf, they rule sizable wading pools with asperity as lesser creatures feed on their shit and clean their nutrient-loaded toenails. Elephants cross truck routes and are followed to subterranean water sources by smaller creatures who suck up the leavings their stomping has unearthed. Even thirstier male sand grouse—whose avian order isn’t famous for its flying prowess—are airborne every day for many hours during the long dry season till they reach moister climes as much as 20 miles away, where they not only tank up themselves but store several tablespoons of water in their breast feathers so the chirpy-chirpy-cheep-cheeps they fly back home to won’t die of thirst.

The best way to watch the five episodes is consecutively, though admittedly the first, which affords Obama the chance to hold forth from the Hawaiian seacoast of his youth before a hither-and-yon world tour that includes Japan and the Great Barrier Reef, is the least jaw-dropping, and note that as welcome as the penguins of Patagonia always are, their struggle for survival is far from cute. But astonishments aplenty await. Footage of the little-seen Sumatran tiger from automated remote cameras. One of many breeds of the Asian slow loris, the only venomous primate on the planet, who can literally rot your flesh if you rub them the wrong way.

And multiple species of what I’ll crudely designate monkeys, most spectacularly Madagascan lemurs, make impossible leaps from tree to tree, plummeting earthward before they grab a lower branch next door and start mapping their next move. Most memorable was a smallish Sumatran species whose young cling to their mothers until they’re adjudged ready to take a flier. I swear I could see the anxiety on one youngster’s face until he or she accepted that Mom wasn’t coming back, and the determination as I held my breath until the next tree was grabbed, which I wasn’t so sure it would be. Yet in a way the biggest prize of all was just about the smallest: a still unnamed hammerhead worm the length of a fingernail poisoning and consuming a juicy slug.

Magnified as it was on film, this was quite a feat—almost surreal in its way. But surreal it isn’t. It’s one of the uncountable ramifications of our physical world, of a biosphere that’s both miraculous and in peril. Like the ex-president we miss so much says: “In this world that’s getting warmer and more crowded, we have to do more.”

A lot more.