It took over a year for Jeff Sharlet’s 2008 The Family—an exhaustively researched report on the below-the-radar cabal of rightist Christian influentials that refers to itself by that vague, anodyne, all-inclusive name—to gain the critical status it deserved. It was a decade more before the book turned into a Netflix five-parter centered on the “nondenominational” National Prayer Breakfast, the subtlest and most effective of the Family’s many plots against America. As it happens, I gave The Family its first rave in late 2008 on the leftwing news site Truthdig, where secular humanists took me to task for suggesting that some Christians were nice enough guys and gals even so, a heresy to which both Sharlet’s book and my own experience as an ex-Christian atheist attest. The Family’s political purpose was dissected and fleshed out in its Netflix version, where the book’s sympathetic portrait of many individual Christians failed to make the cut. But I loved Sharlet’s deeply felt, formally audacious final section, which sketched a sizable scattering of born-again Christians—men and women whose ideologies, psychologies, and access to power varied widely and whose connection to “the Family” was tenuous if that. Sharlet’s This Brilliant Darkness: A Book of Strangers stretches and showcases this aspect of his spirit and formidable talent.

This Brilliant Darkness is anchored to dozens upon dozens of evocative photographs by Instagram amateur Sharlet, some color and some black-and-white. Eighty pages in I thought the entire text was going to comprise one-page essays/captions for these photos, each profiling a citizen Sharlet met while battling insomnia or driving the mountains between Vermont and his father’s house in Schenectady. How he’d maintain narrative momentum I had no idea until I found out he wouldn’t. Instead he devotes 200 pages to three illustrated profiles unattributed to any periodical, though the first two had rather different lives in GQ, where one won a National Magazine Award, and the third was in the online Longreads: Cameroonian immigrant murdered by cop on L.A.’s Skid Row; Russian gays in perpetual fear for their lives; starving, motel-dwelling 61-year-old SSI recipient and her pet plant. After that more briefs provide closure, only instead of working-class strugglers these are mostly druggies or close to it, tough losers rather than as-yet-undefeateds. The beginning and end are constructed around Sharlet meditations on suffering and death, which he’s earned as a man who started writing this book around when his 79-year-old father survived a sextuple bypass only eventually he didn’t—and also a man who while writing this book almost died of a heart attack himself at 44.

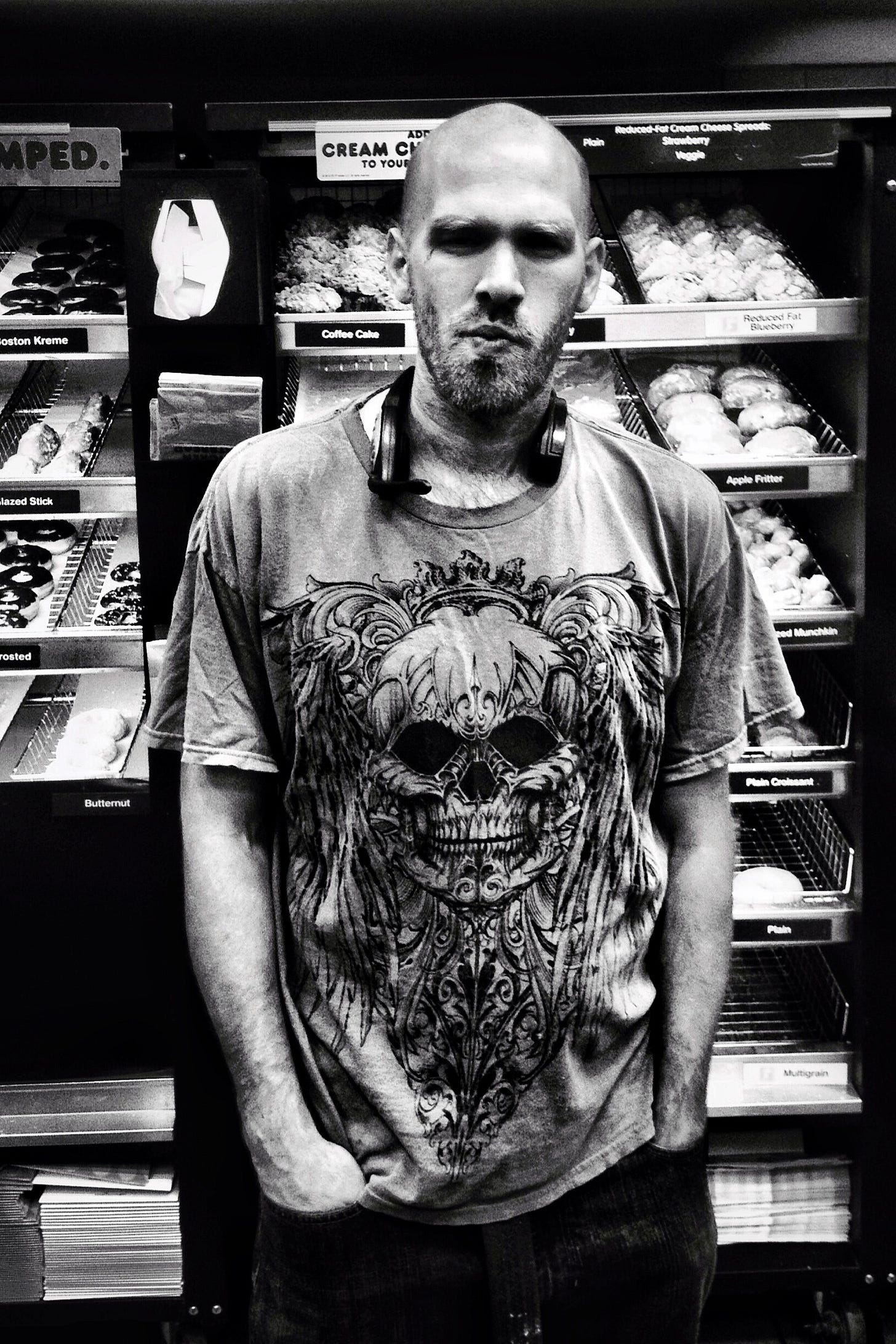

Above: Dunkin’ Donuts night baker Mike

I emphasize these matters of shape and decorum because, while I believe fervently in reading books for information and/or narrative pull plus linguistic pleasure, I’m aesthete enough to feel better when I finish one that having provided these amenities snaps or folds shut into a whole that feels surprisingly right. What clinches Elmore Leonard’s Maximum Bob is the judge’s foolish wife returning to save the day; Marshall Berman’s All That Is Solid Melts Into Air wouldn’t be nearly as satisfying if it didn’t offend capitalist straights by culminating Marxist meditations on Goethe and Baudelaire with an always outrageous, sometimes silly, reliably idea-packed fantasy about the Cross-Bronx Expressway. Similarly, the journalism both thumbnail and longread here never insults the reportorial verities even if Sharlet felt the need to rewrite most of it. But I’m doubly impressed by the way he simultaneously slows and speeds the pace as the book approaches the finish line, setting up and indeed justifying an almost metaphysical two-page close that ends: “This moment. The color. The yellow slash of the headlights across the snow. The red in my veins. The blue sky, same as the snow-covered land. This brilliant darkness, with which I am coming to terms.”

Begin This Brilliant Darkness by meeting a male Dunkin’ Donuts night baker about to switch to house painter, a female Dunkin’ Donuts night baker about to switch to security guard, a Taco Bell night manager trading quesadillas for coffee, an SSI dad pining for his young daughter, a temp night road worker with dreams of Alaska, a Ugandan “bishop,” and more. Then turn a full page that says just “Be Here Soon” to immerse confusedly in the geography and sociology of Skid Row. As is true of all three of the extended pieces but most complex and striking with this one, a verbal-snapshot-by-verbal-snapshot portrait of Charly Keunang and his Skid Row neighbors—all full-fledged human beings with histories and values whatever the desperate details—that keeps building into something larger. Somehow Sharlet manages to view body-cam footage that proves Charly was murdered by a police officer even though the perp will never do time for it, to locate Charly’s sister in Massachusetts, to stay in touch until an unnamed party comes up with the considerable cash it takes to bury Charly back in Africa.

Above: Mary Mazur and her pet plant

The other two longreads are almost as deep. There are moments when you fear not just for the very different Russian gays he meets—including a cooperative-with-children headed by two gay and lesbian couples legally married across gender lines—but for the reporter himself. The tribulations of Mary Mazur, who has funds to buy frozen meals but no way to heat them up, are less perilous. But as with its two predecessors as well as the loosely linked short takes from Sharlet’s Vermont-Schenectady run that bring the book back down to size, all these stories leave the reader painfully conscious of how fragile what we think of as a decent normal life can be. Even in this garishly wealthy nation, not just happiness but dignity and stability often require good luck. The main purpose of This Brilliant Darkness is to impart a tiny portion of permanence to the honor and ambition that Sharlet wants us to know infuse unlikely people in unlikely places. Dark but also brilliant, it will stick with you.