Grim, Funny Memories of a Vanished Manhattan

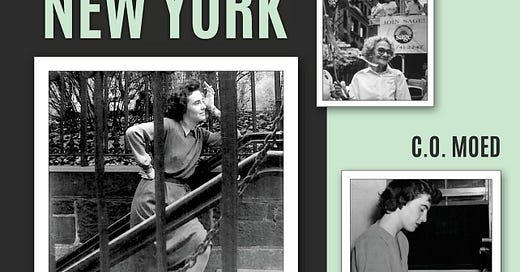

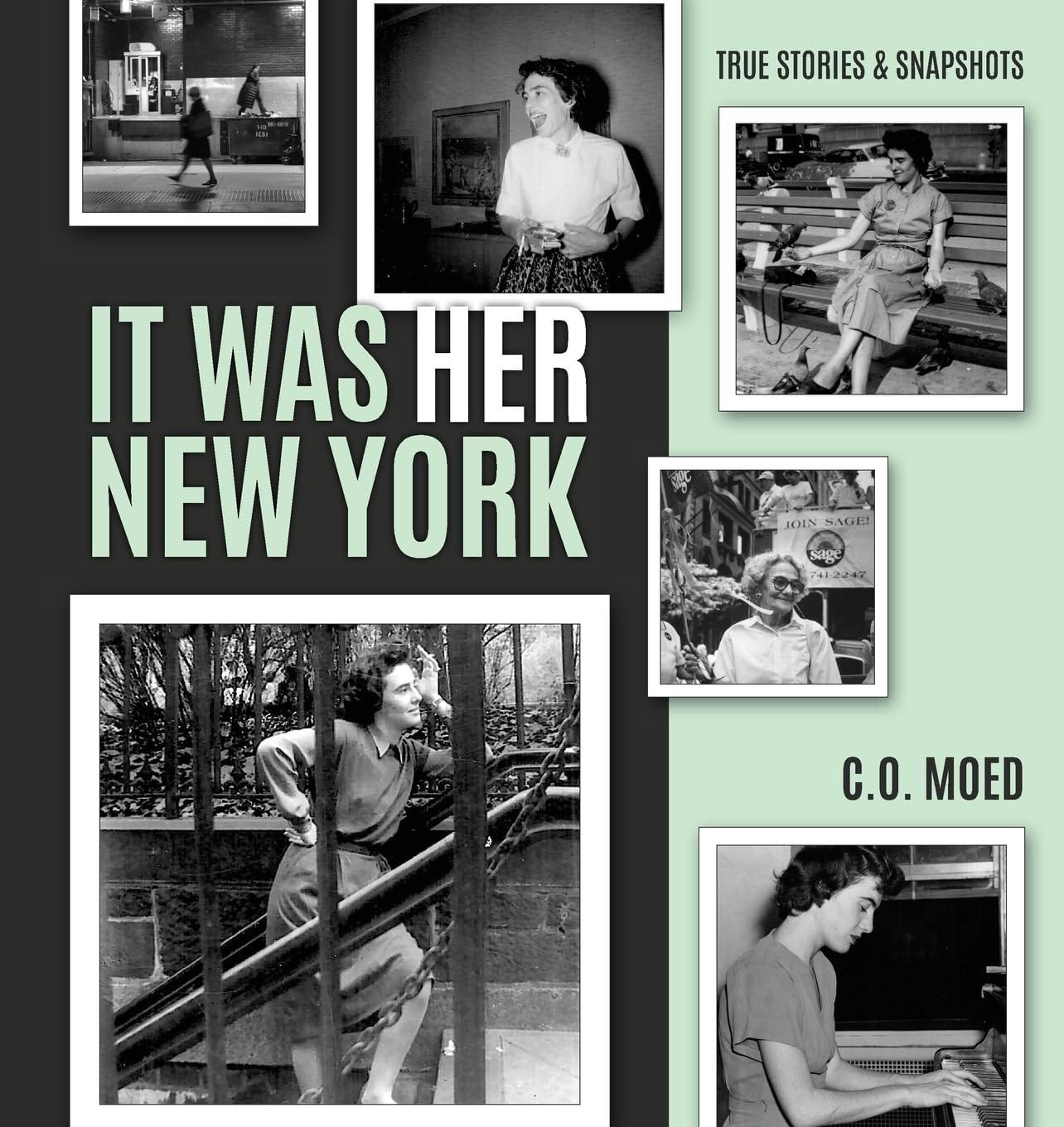

C.O. Moed, "It Was Her New York: True Stories & Snapshots" (2024, 184 pp.)

In 1975, a year after Carola and I got married, we relocated from Avenue B to the not quite spacious seven-room Second Avenue apartment we're still fortunate enough to make our home. The six-story building was such a find that soon we’d tipped several friends to vacancies—old Village Voice hands Vince Aletti and Tom Smucker both still reside upstairs from us. But Claire Moed became our neighbor even sooner than that, when she and a roommate moved in directly upstairs from us during our first few months. We soon learned that she was only 17, which impressed us—in an East Village not yet a boom town, finding such a place was a coup that took some doing. Before too long her lover Joni Wong became a fixture who lasted years, and although she long ago moved to Oakland she often comes back to visit as additional roommates female and occasionally male came and went. One of the males broke Claire’s heart. Another married her.

Over the years high school grad Claire worked her way through Hunter with some support from her divorced mother, a Juilliard-trained classical pianist who earned her living giving lessons. Claire and Carola became friendly, and eventually Carola worked out a rental deal that freed her to work far from my music in Claire’s place during the day; eventually a lot of The Only Ones was written up there. But Claire too was a writer when she could squeeze in the hours—“You have to train for that,” her mother had warned her—and for reasons not merely neighborly we attended a few of her readings. These were painless but not in my recollection compelling. So when I learned she had published a book, I was more impressed than enticed—until it transpired that Carola had bought me my own copy and thought I should read it because she’d liked it so much. Soon I wolfed it down, because so did I. Several pals I urged to buy one also became fans.

So our friend upstairs has now gone public under the moniker C.O. Moed, author and photographer of the nine-inches-square, plentifully illustrated, 184-page It Was Her New York: True Stories & Snapshots, with her mother Florence the unnamed female of the title. Most of it takes place in the now nearly vanished Jewish Lower East Side, a neighborhood centered well south of Houston that stretched west of First Avenue only when necessary, where Florence spent her entire adult life not counting a few brief but by her standards lucrative waitressing forays into the Catskills. As Carola once put it to me, it’s fundamentally a credible story about ordinary people being kind to each other—most of the time, anyhow. But even more it’s a loving, comic, exasperated, episodic portrait of Claire’s opinionated, obsessively frugal mother, who by denying herself and her two daughters such amenities as a decent cup of coffee, an extra blouse, or sometimes even—after all, she rode a bicycle into her sixties and thought a sweater sufficient protection from the winter cold—a medium-length bus ride, manages to keep all of them alive in a small sixth-floor apartment most readily reached via a very small elevator.

As Moed is set on making clear, It Was Her New York is very much rooted in a departed neighborhood. It’s very much a memoir as well as a social history and a character study, with chapters that include many of the finest and funniest recounting Claire’s own growing up, which of course was deeply inflected by her parent not parents—while still alive her absent father is a distant figure, and as we learn the great love of Florence’s life was a woman she didn’t see for decades after the relationship ended. Claire convinces Florence to buy her a bikini and the top falls off when she jumps into the pool. Her friend Sheynah introduces a gaggle of girls to a library book called How Babies Are Made, where they learn “that not only did our fathers have one of those but that they did that with our mothers,” leaving them “numb and shocked”—“until we discovered dirty jokes.” She figures out how to avoid socializing during lunch period at the snooty High School of Performing Arts. Yes Florence loves Frank Sinatra as well as Debussy and has pretty much memorized Singin’ in the Rain, which she compels Claire to watch with her many times. Yes she makes sure that Claire pronounces Loew’s “Low-eeez” not “Low-ssss.” Yes as someone who laboriously nurtured her own technique on the Steinway Claire does’t understand how she could ever afford, she’s a tyrant when it comes to her faithful daughter’s violin practice. But the meat of the book describes her slow, painful, complicated decline and death as Claire, her more distant sister Louise, and a shifting cast of aides, nurses, physicians, drivers for hire, and good Samaritans do what they can to make this willful woman’s last few years on earth something like bearable.

Although as indicated it’s plenty funny, a book that asks “How many times have you seen your mother’s vagina and urethra and asshole?” isn’t there just for the jokes. But it’s never anything like gruesome. As an aide named LaTanya observes, “Nobody wants to clean someone’s behind. The work is boring, you don’t use your skills, and you’re indoors. But you help people from their perspective.” This has been Claire’s way while perhaps slightly expanding what that perspective entails. She and her mom march together in the gay pride parade and Claire takes her to a dyke bar for her 60th birthday. Even after Florence turns 60 they bicycle together sometimes, and once they ride the Staten Island ferry together just so they can get off and run to the next one back to Manhattan. As Florence’s health deteriorates these respites pretty much disappear. But the humor does not, though it definitely diminishes. Sure it’s funny when Florence complains that Claire’s rendition of “Singin’ in the Rain” is out of tune, but not that funny. Claire only learns how much she loves the meatball sandwiches at Rosy’s because friends give her bites—Florence sticks strictly to bologna she buys herself. Yet her loyalty and her love endure until Florence dies. And before that inevitable denouement Florence says “I love you” and Claire responds in kind. “I never said that to anybody,” Florence goes on. Claire: “I know.” Florence: “How do you know?” Claire: “I know you.” On the first day of Rosh Hashanah, Florence dies with Astaire, Fitzgerald, and Sinatra in her ear courtesy of her doctor’s new iPhone. She dies in the hospital holding Claire’s hand, because Claire lied with knowledge aforethought when she promised to take her mother home. “Afterward, I stepped into the morning air with knowledge that only comes from absolute endings. I was no longer the child who had failed her, but a woman who survived a decision.”

The book isn’t over with the death, though. The scene where three men wrestle the Steinway that won’t fit into that tiny elevator down six flights of stairs on the crucial first step of its journey to a Bensonhurst community center epitomizes ordinary people being kind to each other as all three of them are pushed to their physical limits. But her conversation with cab driver Mr. A from Togo, who hasn’t managed to get home for five years, is almost as wrenching in its own way, as is Claire’s failed struggle to retrieve her mother’s letters to the only woman she ever truly loved from a family set on concealing all evidence that the relationship ever happened. So this book will have to do. And it does.