Fixing A Hole (Or Wikipedia)

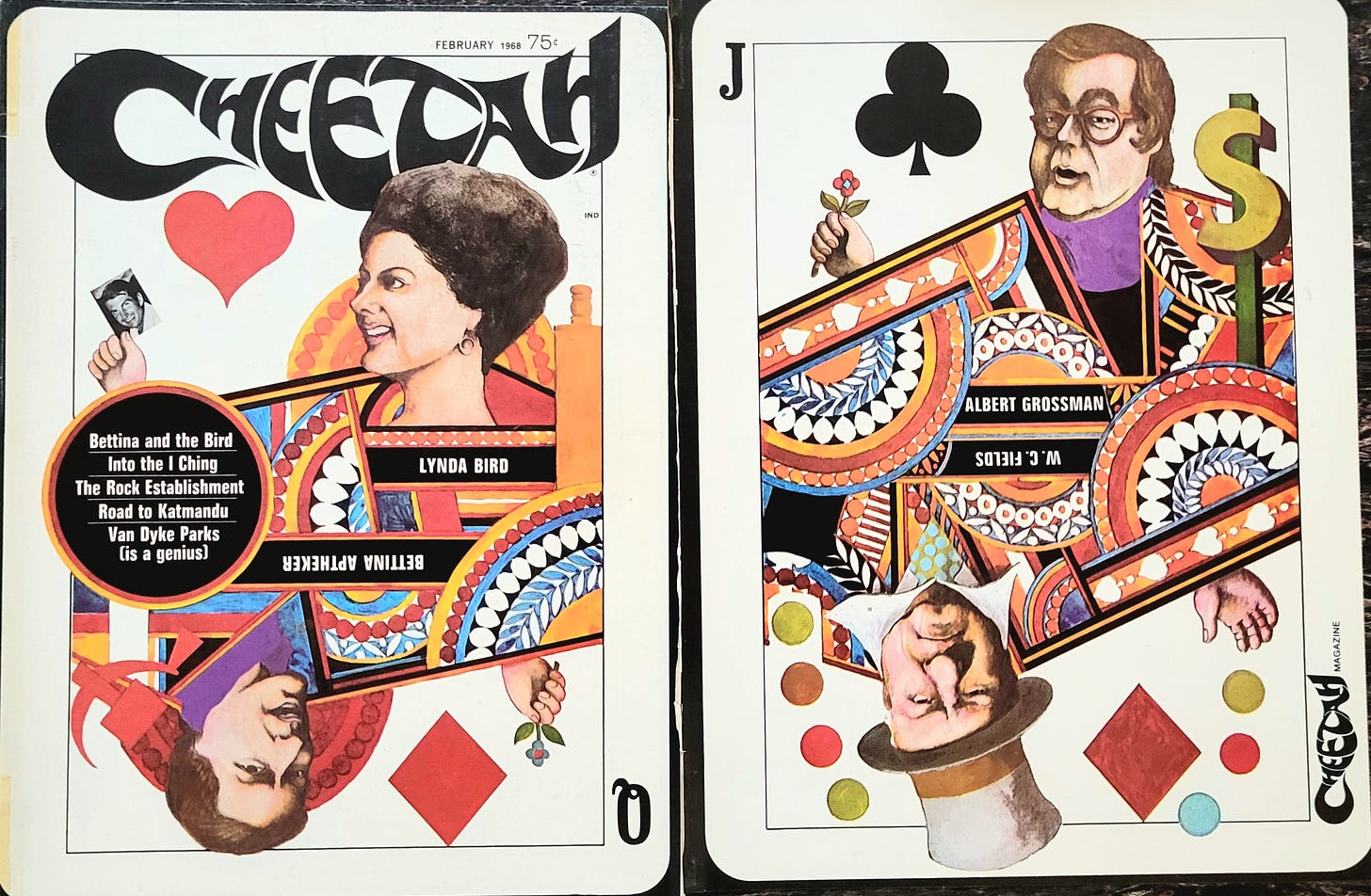

On the vagaries of the Wikipedia entry for "Cheetah" magazine, and an excerpt of a piece from the February, 1968 issue.

Like you I bet, and if not why not, I occasionally avoid actual work by looking up this or that object of momentary curiosity in Wikipedia—an enormously negotiable if not absolutely reliable source of basic facts about moderately prominent friends and acquaintances as well as historical incidents and cultural oddments of every description. (Donate—I do.) Thus it came to be that one day early this year I searched Wikipedia for the short-lived weekend-hippie slick magazine Cheetah, where I published features for most of its nine-month life and also served as a volunteer editor starting say August-September 1967, all of which I sum up on pages 184 through 188 of Going Into the City. What came up is reproduced to begin this post. It is so wrong factually I did what I could to alert Wikipedia, but found the process an impossible tangle. Here’s hoping someone else picks up the slack.

As Wikipedia indicates, this article is only a “stub,” which means it needs shoring up both lengthwise and sourcewise. In the four or five months since I made my discovery no one has bothered. So I fiddled around myself a little and before too long found a one-pager from Time magazine that ran in December 1967. Easier to find than Going Into the City and also more authoritative, it backs up most of what I’ll outline below.

Cheetah was the name of at least two rock-era discos, which arose briefly in the early hippie era in Los Angeles’s Venice Beach and at Broadway and 52nd in Manhattan, a few blocks north of Cheetah magazine’s offices. Matty Simmons, eventually the prosperous proprietor of the National Lampoon and Animal House franchises, started Cheetah magazine having already had success with Weight Watchers magazine–reasoning, apparently, that because Cheetah was a club like Weight Watchers was a club its members would scarf up one magazine the way they had the other even without new recipes to lure readers in or for that matter a mailing list worthy of the name. Its first editor was Jules Siegel, a rising 30-something journalist who was on the music beat early and is now remembered mostly for his adoration of Brian Wilson, with whom he conducted stoned interviews that became all but canonical among Beach Boys devotees. He also signed off on my first major piece of rock criticism, “Rock Lyrics Are Poetry (Maybe).” A serious stoner even for 1967, Siegel was soon replaced by second-in-command Larry Dietz, who I knew through the New York Magazine cabal and had assigned the Rock Lyrics piece. Dietz in turn hired as his assistant editor Ellen Willis, who’d been my girlfriend for a year-and-a-half by then, during which time she labored through a seminal Dylan essay for the not yet quite neocon Commentary–a piece of work so mindbogglingly new and right in its insistence that what was most original about Dylan wasn’t how he generated verbal imagery but how he disported media celebrity that it became an instant classic and soon sparked her emergence as The New Yorker’s first rock critic. The version that The New Yorker picked up on wasn’t the Commentary one, however. It was the expanded rewrite Dietz had asked her to work up for Cheetah, which is now the official version of that seminal piece of rock criticism, as it should be.

Ellen Willis was something else, absolutely. As brilliant a person as I’ve ever met. Worked hard at Cheetah until Simmons’s partner Len Mogel figured out that she was a Red and offed her. Did not, however, invent the magazine, which was not, moreover, a “rock” magazine no matter what the two hard-working but not therefore fully informed Scandinavian academics who authored Rock Criticism From the Beginning, which is cited in that unfortunate Wikipedia Cheetah stub, have to say about it. So somebody vastly improve that article please. Willis’s own Wikipedia entry could be fuller, too, actually.

Below, meanwhile, find the first part of my Cheetah hitchhiking piece “A Hungry Thumb to Western Nebraska,” which ends well before I drive a car that picked me up off the highway into a ditch, where once the car was right side up again and the police had ascertained that the cut on my head was superficial I learned that the car’s just-out-of-med-school owner had left his registration home, which was in Mississippi. So until the documentation arrived in the mail, the owner and I spent two days in jail in Sidney, Nebraska. When I was released I proceeded to the Greyhound stop and took the bus the rest of the way to California.

A HUNGRY THUMB TO WESTERN NEBRASKA

On Thursday, Woj and I had driven to Sheboygan in Woj’s old Cadillac convertible to see Basil get married. We spent four hours there and then raced back to Chicago, Woj chugging on a bottle of champagne as he made for South 55th Street. I had thought I might strike west from Sheboygan, so my pack was in Woj’s trunk; I put it on my back when Peter took me home on his motorcycle. The pack weighed 40 pounds with the new sleeping bag on top, and I was a little worried about balance as we sped down Lake Shore Drive. But there was no trouble.

My own car, a 57 Chevy, was home in New York. I loved it too much to kill it on a long trip. Since my schedule was looseI could have obtained a California car from a drive-away agency, and I had enough money to take the bus. Instead, I decided to hitchhike.

I was 24 and had logged only 500 of my 35,000 hitchhiking miles in the previous two years. But I guarded fond memories of cross-country journeys in 1963 and 1964, the first a leisurely two-week camping trip, the second a three-and-a-half day dash across Routes 30 and 40. I had to try it again even though I knew the way had changed. Interstate 80 was now complete along most of my route.

Interstate 80 is a wide-shouldered, skid-resistant, four-lane divided highway that bypasses everything; it runs parallel to 30 most of the way to Ogallala, Nebraska, confluent with 30 through much of Wyoming, and confluent with 40 west of Salt Lake City. Roads like 80 lace the country and they are not pleasant for hitchhikers. Hitchhiking is prohibited on the interstates, and while in open country there is little chance of arrest or even banishment, the possibility is always unsettling. Furthermore, Interstate is depressing, not to drive or ride, as the face-of-America people insist, but to hitchhike. The anonymous cars that zoom by at 75 offer no solace to the lorn wanderer, nor are there Coke machines to lend him comfort. But those Americans who are driven by whim, duty, or disaster to cover long distances in short time, and who prefer no means of travel to their own automobiles, go Interstate, and the hitchhiker has to follow them. So I was taking 80 west.

Friday morning I wrote my girl and told her I’d be there Tuesday; in truth, I hoped to outrace my own letter. Woj picked me up at Peter’s at 10:30 in the company Chevy and headed for the Southwest Expressway. It is almost impossible to hitch out of Chicago without a lift to the outskirts. The city is hatched and girdled with superhighways, and catching a ride on one of them is both risky—because of police—and frustrating—95 per cent of that careering traffic is local and just gets in the way. The plan was for Woj to locate me at the junction of 30 and 66, some miles east of the beginning of 80, but I didn’t like the look of it on the map. Route 30 was really the Tri-State Expressway, Interstate 294; the interchange was certain to be heavily policed. Just east, in Countryside, there appeared to be a promising spot on 66, and when we got there my instinct was corroborated by a stop signal, flowing traffic, and a place to stand, But as we brunched at a Hi-Boy—double hamburgers, malteds, pie, my treat —I thought again. Wasn’t 66 a local road to Joliet? Woj shrugged and agreed to take me farther along the Southwest. Maybe there’d be a good place. But there wasn’t, and he had to get back to work.

As Woj brought the Chevy to a stop at the bottom of the off-ramp, I spotted a new-looking pickup signaling for the westbound on-ramp across the road. Grabbing my notebook, my FRISCO sign and my sports jacket and hoisting the pack on one shoulder as I thanked Woj, I jumped and ran. The pickup slowed for the turn. I waved my sign. The pickup stopped. Woj honked and drove off.

I was told to throw my pack in the back of the truck with an orange machine that looked to me like a giant Erector toy. I wondered what my driver had to do with the machine. Only farmers drive pickups, and this guy looked like one, broad and ruddy, but he wore dress slacks and a short-sleeved white shirt; a jacket that matched the slacks and a clip-on tie with Windsor knot lay with some papers beside him. He had the kind of smooth, genial face that can conceal anything. A salesman?

As long as we were moving I didn’t really care, and thus I neglected my basic duty. Hitchhiking is a tacit exchange between ride and rider-miles for diversion — and I usually feel obliged to start conversation. But in a truck all obligations are obscured by the noise of the engine; pickups are nowhere near as bad as semis, but they are bad enough. I offered a few particulars to the farmer-salesman, then shut up, glad he evinced courtesy rather than interest. Once in a while he’d ask a question, then withdraw again. I began to drowse as we consumed an unobstructed mile of brown farmland every minute.

But soon his interjections came more insistently. He interrogated me until seemed to have exhausted my material, then began to reveal himself. He was a farmer near Decatur. He liked rural life. He was fairly successful. The machine in back was used to spread artificial fertilizer. He wondered what a city boy like me knew about artificial fertilizers. Did I know scientists believed artificial fertilizers caused mental retardation? Did I know the expense of natural fertilizers? Did I know how every farmer had to endanger those he loved most? His own daughter, why, his own little daughter had been born the victim of mental retardation. How he had brooded through the long winter nights, wondering why it should happen to him. How he had worked at his desk all winter and designed a distributor to allocate the proper amount of fertilizer to each plant, so the excess could not poison the unborn loved ones of helpless farmers. He had built working models in his barn and farmers bought them until he could no longer satisfy the demand. Just now he was returning from International Harvester. He had sold them his invention for several hundred thousand dollars. His daughter would attend the most advanced schools. He did not believe she would get better.

The farmer was flushed, his white eyebrows clenched above his bland blue eyes. It was impossible to interrupt. The accent was hick, the phasing awkward, the ideas primitive, but I had to listen. He had hardly begun. He moved from the ambit of his own pain out to the pain of men everywhere. His fervor was evangelical. Confidently, I waited for the pitch.

“I do not know you, I do not know your likes and dislikes, but I do know this—there is a hunger abroad in this land, and people everywhere are desperate to satisfy that hunger. I went to St. Louis this spring and I saw thousands of cars all moving towards the Mississippi, and I stopped at a filling station and asked the attendant where all of these cars were going. And the attendant told me they were going to the new baseball park.

“Fifty thousand people” — and his voice began to thunder—”fifty thousand people spending Sunday afternoon watching a man hit at a ball with a stick” — I started to protest, but he rolled on — “fifty thousand people who didn’t know what else to do with their lives. And I said to myself, ‘What a waste of human personality that fifty thousand people should spend a beautiful afternoon in a baseball park, lining the pockets of a brewer of beer! What a waste of human personality! And what hunger there must be inside of them” — the pitch was coming— “a hunger they cannot satisfy.

“Last night in Chicago I took a walk after dinner and found myself on South State Street. Do you know the neighborhood?” The question was rhetorical. “And I saw a sign that said: ‘Burlesque Tonight.’” A sign on the road said “Bloomington 70”; I began to calculate as I listened. “I had never been to a burlesque show so I decided to see for myself. I went inside and asked the price and the man said, ‘Three dollars for a bottle of beer.’ I told him I don’t drink beer, how much would it be for a Coke, and he said, ‘Three dollars.’ ‘Three dollars!' I said. I can’t pay that, I’m a Republican, but I’ll tell you what I will do. I’ll give you 25 cents to stand and look for a while.’”

“I think I missed my turnoff,” I said.

“How do I know whether you missed your turnoff? Don’t you know where you’re going? And the man said, ‘Well, if you're gonna stand, stand in the back near the door, and don’t stand long.’ So I stood and watched the faces of these men who drank three-dollar beer as if it was water while a half-naked girl danced in their faces. And I thought what a hunger there must be inside them that they would degrade themselves on beer that cost three dollars a bottle while a young girl danced in their faces. Oh, no—I didn’t stand too long. After a few minutes I went back to my hotel.”

His voice rose toward the end, and then there seemed to be a pause. So I interrupted again and asked to be left in Dwight, where I could head north to 80 on 47. The farmer tried to convince me to accompany him to Bloomington, two more hours out of my way, and it was only when he had run out of spurious arguments that he returned to his previous theme. He told the story of a young hitchhiker he had once encountered in Iowa, how he had put him up for the night at a hotel, and how the boy, out of lust or gratitude, had offered to make love to him. How he had politely refused. And what a hunger there was there. Then we reached Dwight.