Deconstructing Reconstruction

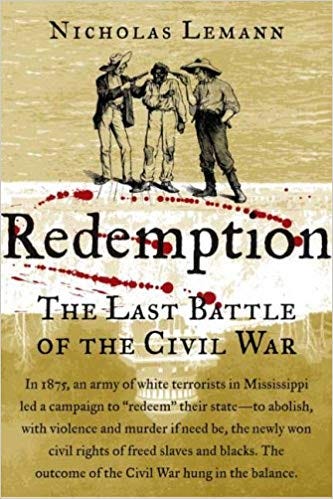

Nicholas Lemann: "Redemption: The Last Battle of the Civil War" (257 pp., 2006)

I only read Nicholas Lemann’s 2006 Redemption: The Last Battle of the Civil War after I was asked to review his new Transaction Man, and thus I caught up just in time. That’s because, as Louisiana-born New Yorker stalwart Lemann may have feared or even foreseen all those years ago, it could have been designed to address the frightening historical juncture that is 2019. Centered on Reconstruction-era Mississippi governor Adelbert Ames, a young Union general whose father-in-law was Radical Republican kingmaker Benjamin Butler, its deepest purpose is to document the racist violence that demolished Reconstruction in Mississippi and Louisiana in the early 1870s. In a sickening succession of riots, murders, and massacres, Confederate veterans demolish black freedmen’s voting rights and uppity educational pretensions in unrelenting acts of armed terrorism, some of which leave trails of dead while others simply send ex-slaves fleeing or convince them to settle for a penury not much better than bondage. The crucial actor here isn’t Ames, however admirable his physical courage and fruitless efforts to convince Washington pols to back up their supposed principles with troops. It’s all the lying, arrogant, brutal white supremacists who succeed in proving Reconstruction an unworkable fantasy.

An auxiliary satisfaction of Redemption is a reminder of the epistolatory eloquence to which so many educated 19th-century Americans aspired, the many long quotes from the correspondence and journals of Adelbert and his gifted wife Blanche, who in 1870 wrote: “What is there that human mind is not capable of fashioning? Ere long the Heavens may be used as the common highway and Jove’s own thunderbolts—no longer simply for destruction—may be utilized for benefit of mankind, in the form of light and heat.” But even more impressive is the less elegant but deeper prose of the freedom-fighting black resistance. Soon-deposed black sheriff John Milton Brown: “On the way, they met up with a preacher, an old colored man named Nelson Bright, and they shot him. He was hunting his mules and had no gun with him at the time. They went farther and killed another colored man, as I understand.” A hurried missive to President Grant from the valiant E.C. Walker: “Pres. I have write the Hon. Governor Two (2) Letters and Pres. I know you Have it in your Powder To Stop White People from Killing Black People . . . now Pres. I will ask your Hon. Doant the 13 & 14 & 15 Demendments Gives the (Col'd) Peopels the Same Rights and the voice to the Balord Box as it Do the Whites.”

Practically speaking, the answer was of course no, which as today’s voter suppressors dig in for the long haul it often still is. Glumly, Redemption draws to a close by recalling Columbia University’s John W. Burgess, “arguably the founder of the discipline of political science in the United States,” whose 1902 Reconstruction and the Constitution established as a truism that Reconstruction’s program of Negro enfranchisement failed to recognize the “vast differences in political capacity between the races.” Lemann follows this calumny to Woodrow Wilson’s five-volume History of the American People, which ended with an even more racist account of Reconstruction, and while such arrant prejudice did gradually fade into the background of Reconstruction’s historical profile, I can attest that the inevitability of its failure was still taken for granted when I attended high school in the mid-’50s. Lemann ends Redemption by noting that this truism was built into John F. Kennedy’s 1955 Profiles in Courage, which disparages Adelbert Ames and lionizes Mississippi senator Lucius Lamar, a key dismantler of the Reconstuction JFK called “a black nightmare the South could never forget.” Kennedy’s racial politics evolved before he died—unlike Grant, he sent federal troops to the South to enforce African-Americans’ civil rights. But despite repeated protests by Ames’s heirs, the text of Profiles in Courage remains untouched.