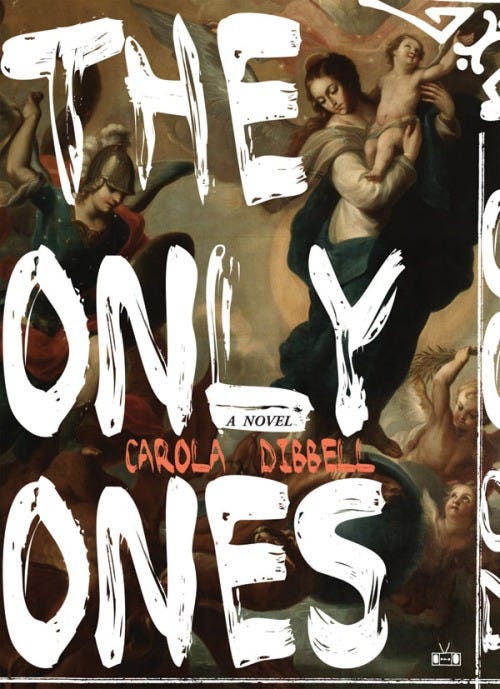

Of course I’m not “objective” about this all too timely 2015 novel. Not only did my wife write it, I helped, from conceptual speculation and plot strategems to line editing and proofreading. Yet oddly, I never downed it cover to cover—the two times I read the whole thing consecutively, in 2009 and 2010, it was still in manuscript, tweaked and improved the second time by her agent but not yet speeded up by her editor at Two Dollar Radio, who only surfaced in late 2013. When it was finally published in March 2015, naturally I opened it up to see how the changes looked and reread my favorite parts for the dozenth time. But only this month did I have the pleasure of racing through the bound The Only Ones beginning to end, chortling often at the beginning and weeping for several minutes toward the end.

By coincidence, The Only Ones came out just a month after my memoir, Going Into the City, and though Carola wasn’t as widely or prominently reviewed, her notices averaged more enthusiastic than mine. That Christmas, in a brazen meet-cute move, both books made the 2015 top 10 of Oprah Winfrey’s O magazine, Carola’s fourth and mine eighth. We did a few readings together, but in New York and elsewhere—Oregon, Iowa, Rochester where she won a Writers & Books Debut Novel award, Paris and Biarritz en français after she was “traduit de l'americain”—she scored more of her own.

In 25 words or less, The Only Ones is the story of a brutally poor, inexplicably immune young woman who brings up her own clone in a pandemic-ridden near future. That slotted it “dystopian,” a critical buzzword handy for taking the onus of crass “science fiction” off the literary likes of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale and Cormac McCarthy’s The Road. But there are many fictional dystopias—Atwood’s totalitarian patriarchy is far from McCarthy’s postnuclear wasteland is far from the flooded yet functioning cli-fi Terra of prolific science-fiction polymath Kim Stanley Robinson. The Only Ones’s dystopia was a world radically depopulated by contagion, a premise it had in common with two other novels whose authors Carola shared podiums with in 2015: Emily St. John Mandel’s renowned Station Eleven, which I heartily disliked, and Sandra Newman’s underappreciated The Country of Ice Cream Star, which I admired so much I wrote up her entire oeuvre for Barnes & Noble Review.

These days, unsurprisingly, the New York Times is one of many publications to run surveys of pandemic fiction; I’ve ordered Ling Ma’s Severance from the Strand and look forward to The End of October by Lawrence Wright, who has told Publisher’s Weekly that he hopes our new disease “turns out better in real life than it did in my novel.” I take it Wright’s approach is to recount a pandemic the way Albert Camus’s The Plague and Daniel Defoe’s Journal of the Plague Year did epidemics, although Defoe, whose just-the-facts naturalism Carola admires in her warm and waggish way, does nail international travel as a vector of infection by tracing the disease he chronicles back to Amsterdam. In Mandel and Newman, on the other hand, contagion is basically a plot device, deployed to clear room for new worlds their authors want to imagine. Mandel’s plague kills almost everybody almost instantly, leaving her free to home in on a traveling Shakespeare troupe of survivors, whereas Newman’s “posies”—Kaposi sarcoma, right?—proves an impossibly ruthless killer in a Nighted States whose white population was long ago wiped out by something called WAKS. This frees her to spend the first third of her 580-page tale in the barely populated “Massa woods” near Lowell, where four tiny tribes of historically Senegalese youngsters try to survive past 20 and a genius named Ice Cream Star gets to lead her people’s exodus in a poetic prose of Newman’s own devising.

Pandemics are a plot device in The Only Ones too, but there’s more science in it. Artistically, Carola’s goal was what she described as “a novel about bringing up a child, told as science fiction”—a novel inspired by but not based on her experience raising the two-week-old girl we adopted after a decade of infertility treatments. Her brainstorm was to turn adoption on its head by having the mother raise her own clone, with the pandemic twist in there to render cloning a plausible goal in a microbe-beset world where bringing a child to term is very nearly a miracle. Having spent years learning more than she wanted to know about the biology of conception, she researched cloning too, and the molecular-biology machinations she details for some 30 pages, while not strictly speaking realistic—no one has yet cloned a human being—turn informed scientific speculation into a suspense story. Much the same is true of how pandemics work in a novel that goes on for two decades. Far from a spawning ground of new beginnings, this is a radically diminished world where lives are organized around surviving what comes next and making do with what’s left in a world where empty streets can suddenly teem with masked crowds caught up in an “exodus” from the latest hit—Mumbai, for instance, which surfaces early in the novel and spreads so unstoppably that some classify it as a “slatewiper” like 2040’s Big One.

Well-rendered as these details are, however, they remain means to an end in a book Carola stuck with most of all because she owed it to her narrator: Inez Kissena Fardo, a 19-year-old from epicentric Queens who at just a few days old lost her biological mother and at 10 lost the stepmother who had plucked her from a Kissena Boulevard bus with its driver dead at the wheel. Then come years pimped by two pairs of brothers, all four of whom die none too soon, and freelancing at Powell’s Cove in College Point, where the working girls are presumed disease-resistant “hardies” suitable for sexual congress and other monetizations of their bodies, like selling their teeth—or the courier gig that takes Inez to rogue veterinarian Rauden Sachs in the lower Catskills. Rauden is a hard-drinking genius who clones Inez after determining that she’s what his mentor Dewey Sylvain had always argued was possible—a “Sylvain hardy” immune to every disease period. After the bereaved mother who’d financed the eight-month procedure backs out, Inez, who’s barely glimpsed a baby before, is sent off to raise the clone, whose name is Ani. For the next 250 pages, she describes how that worked out—not to some imagined “reader,” but to other clones of hers she’s learned are just a Web-traversing DNA swipe away.

What propels The Only Ones is Inez’s voice, which Carola lucked into a full decade before the book came to market: the observant, skeptical, sarcastic, stealth-intellegent demotic of someone who always wants to find out what happens next. It gains detail and vocabulary as Inez integrates the jargon of Rauden’s somewhat safer and much more knowledgeable world into a manner of speaking that still puts survival first. Its spirit owes both the basic-English simplicity of rock and roll and the tuff-guy irony of punk. But it’s Inez’s own, and it makes the book move. Some lay readers were offended—“kind of like being on the 7 and listening to someone annoying talk through an interesting story on their cell,” huffed one Queens-based Amazon commenter ripe for Emily St. John Mandel—but others couldn’t get enough, and most reviewers were dazzled. The vitality and sheer spunk of this voice serve to counteract the bleakness of the world The Only Ones inhabits. Even right at the beginning, when you're chortling at how easily Inez one-ups Rauden as she parries his invasive interrogatories, you sense that this young human has resources she’s never had call to tap into. And those resources keep her daughter alive.

If Inez is tough, that’s because for her it’s always been be tough or die—she takes risks with her body not just because she believes she won’t “get anything,” as she likes to put it, but because disease or no disease she’ll die if she doesn’t. Plus she’s been a victim of abuse, once a child prostitute. Hence she’s afflicted with what in Ani’s school years Inez learns to call “the low self-esteem.” Dispatched back to Queens when Ani is barely a week old, she feels impelled to do more than survive just to be the right kind of mother. But she’s not ready for what happens when Ani is “one month, two weeks, four days old”: having finally let Inez sleep through the night, the infant celebrates the next morning by making a popping noise and then winking—and then immediately repeating these tricks, in order. Recalls Inez: “It was very cute.” And that’s when our narrator gets a feeling even better for the soul than self-esteem. We recognize it even if she doesn’t yet, exactly. It’s love.

This isn’t the first time, fortunately—Inez loved Cissy Fardo, who died not in an epi but a fire 10 years after rescuing Ani’s infant self from that bus. When Ani turns 10, Inez suddenly becomes phobically grouchy about flames of any sort. But by then, motherly love has become more complicated, as it always does. Early on Inez obsesses about the who’s-who identity puzzles that cloning brings to the surface (in a nice touch, Rauden’s resident computer whiz is his wheelchair-bound identical twin), and when Ani is five a Board of Ed risen from the dead carrier-pigeons Inez to tell her she’s obliged to send her daughter to one of the schools it’s finally carved out of its ruined red-brick empire. Aware that education is how regular folks achieve “the better life,” Inez wants Ani to attend school, but is soon compelled to outsmart an opaque bureaucracy, and not just because free education costs money—for transportation, clothing, the right backpack. She finds work cleaning the protective domes that sprout across the permeable city line in Nassau County. She sells ova and soma to Rauden, then experiences the exhilaration of agency by taking over the delicate manual work of somatic cell nuclear transplant because Rauden’s gotten too shaky. All good except for one thing—Ani hates school.

This business and more are rendered in some detail, and embedded in that detail are the specifics of an imagined but not altogether implausible dystopia—one much worse than our worst imaginings at this eerily apposite juncture, but not altogether unlike our moment as regards class, more subtly race, public ignorance, government ineptitude, and the even worse world it might portend. Yet what made me cry toward the end was something less grand: a showdown between Inez and adolescent Ani that, while far too plot-specific to pertain to our atypical family, bore an emotional weight that evoked not just Carola’s and my parental travails but, upon reflection, the tsouris each of us leveled on our very different parents in our own unique ways.

So The Only Ones actually is a novel about bringing up a child, told as science fiction. But that’s not all. The ending, which didn’t make me cry because I was ready for it, is, well, sad. But it isn’t really the ending. The ending is about wanting to find out what happens next. Which at this eerily apposite juncture I hope is a lesson, not to mention a possibility, for all of us.