As I expect many do as they hit their eighties, I occasionally Google people from my past: lapsed rock critics, old pals gone thataway, sexual partners from half a century ago, fellow grade skippers at Junior High School 16, and so forth. So it came to pass that one day this fall I was musing about Flushing High School, where I edited the literary magazine and was the youngest graduate in the class of ‘58 at barely 16. Of course I attended our 50th out in Queens in 2008, where I danced less ineptly half a century later and left my best tie on the back of a chair. It was interesting to connect with ghosts from my teens, although I was still in contact with a couple of them. But when I look back I’m struck by how young I was then, and how theoretical my attraction to the female classmates I ranked down to ten, not one of whom I even imagined dating until my senior year.

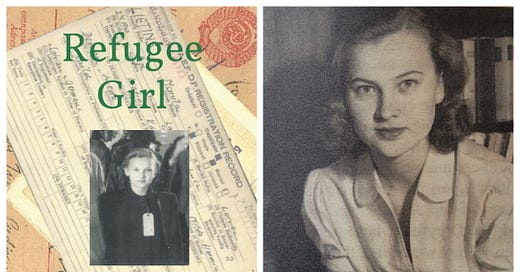

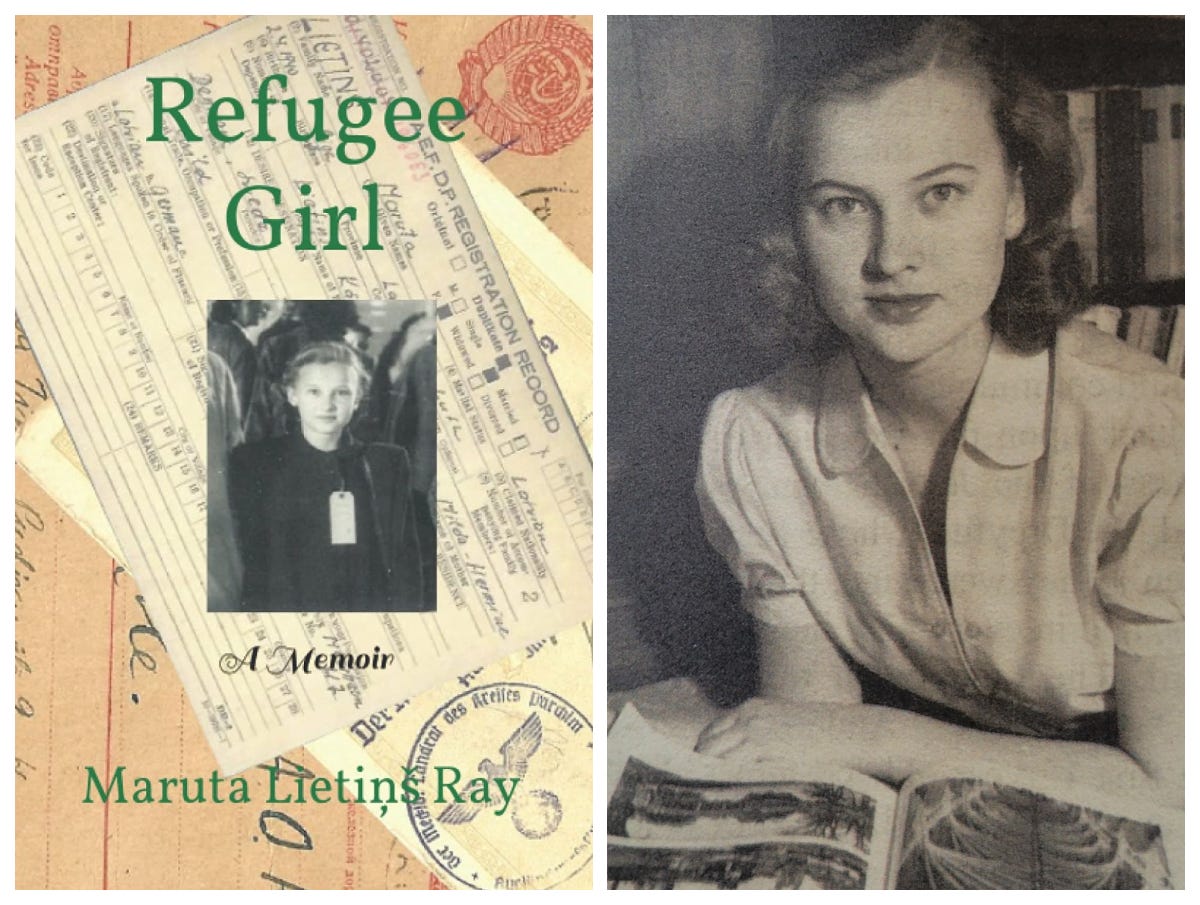

This brings me to Maruta Lietiņš, a manifestly self-possessed, intelligent, and beautiful blonde two years my senior who was so out of my league I doubt I even had the stones to put her on one of my lists. Unusual her Latvian name self-evidently is, however, so a month ago I Googled her and discovered that Maruta Lietiņš Ray had published a book in 2021. I bought it forthwith. But pungent Flushing High reminiscences did not materialize in Refugee Girl: A Memoir. Maruta, if you’ll pardon the first name I resort to because neither Lietiņš nor Ray feels comfortable, has weightier stories to tell, and she makes the most of them. Thoroughly researched and at times amazing, heart-wrenching, or both, this is a unique and compelling piece of writing.

South of Estonia and north of Lithuania, Latvia, current population 1.9 million, is one of the three Baltic states, all of which became members of NATO after slipping from Soviet control in 1991. During World War II it was buffeted between the communist Russians and fascist Germans, who ruled it from 1941 to 1944, when Russia resumed control. Maruta’s mother, Milda Zilava, put herself through acting school with her earnings as a seamstress and eventually became a Latvian film star so renowned that decades later when Maruta ventured into the Riga City Theater and explained to the director whose daughter she was he dropped to his knees and kissed her hands. Her father, moreover, was the music director of the Latvian national theater. But for Latvians, World War II came with rock-and-a-hard-place dilemmas that Maruta’s birth in 1940 only complicated, especially since the Soviets busily “incarcerated, deported, and killed” Latvian intellectuals as the Nazis took over—her father evaded a Riga roundup by riding trains for the entire night it was underway.

Much of what ensues in Maruta’s account of the European phase of her years as a refugee girl is remarkable for the wealth of resolve, ingenuity, and human kindness it sometimes inspired and sometimes merely occasioned in not just the refugees but the bystanders who for the most part did what they could to help the multitudes caught up in the kind of life crises few of those reading this have ever gotten near. Most impressive in my mind was her endlessly inventive mother, the film star who’d paid her tuition as a seamstress. With all but a single suitcase of her family’s baggage incinerated in a bombing, she enlarged a sweater Maruta had outgrown and crocheted fasteners with no buttons to be had, fashioned “part moccasin, part espadrilles” from a piece of tanned leather, and converted a dress she found in the trash into a bathing suit. Culinarily she fashioned a birthday cake from graham crackers and flavored nettle soup with the water the butcher boiled sausages in. After World War II ended in 1945, when Maruta was between ages five and 10, she and her family lived in displaced persons camps of sparse but gradually improving amenity, and these are also described in candid and occasionally appalling detail. Five years in, on July 12, 1950, with cannilly corner-cutting help from a husband-and-wife team her family knew from the Riga theater world who by various honorable subterfuges also managed to sponsor 30 other Latvians into the U.S., the Lietiņš family got its first look at the Statue of Liberty.

The American chapters of Refugee Girl aren’t as chilling or revelatory as the war-torn European material. But in a moment when immigration is under attack by the nearest thing to a fascist government this nation has ever seen, the details are welcome. True, these were white people, which with said government is all too relevant. But that said it’s worth pointing out that Maruta’s fellow refugees often crowded into housing that would sometimes cram four families into a four-room apartment for a duration whose end date was unknowable. And even when end dates came, the sacrifices the Latvian immigrants made continued—Maruta’s father, a bigshot intellectual back in Riga, had to work jobs in a mattress factory or house-painting so far out on Long Island that he spent six hours a day walking to and from the Long Island Expressway to accommodate the van that took him to work. Nor did onetime honor student Maruta always fit right in as she adjusted to her new circumstances. As the youngest kid in my high school class, I was always impressed by her bearing, beauty, and intelligence. But to her these positives weren’t always so manifest—she wasn’t as smart or successful in school as she thought she should be. She had recently been, after all, a 10-year-old who was stricken with pity for a sailor who caught an orange with a hideously deformed left hand only to learn that he was wearing something she knew naught of—a baseball mitt. But note that what she felt was compassion, not fear or disgust. That’s how she was brought up.

Like many of my fellow ‘58s, Maruta might well have attended Queens College, a jewel of the CUNY system that turned out many distinguished graduates. But instead she won a scholarhip to Barnard, which she commuted to for some two hours a day because her family couldn’t afford the housing—and then did graduate work in German literature at the University of Chicago, won a Fulbright to Germany, and returned to Chicago, where she met the man she’d marry, Benjamin Ray—as she puts it, “a descendant of those very early ‘refugees’ who arrived on these shores in 1620 on the good ship Mayflower.” The only serious boyfriend of her life, Ray—who like Maruta went on to teach at the University of Virginia—has now been her husband for 58 years, with three children and what looks in the family photo like five grandchildren to show for it. Not every refugee gets to have a happy ending. But it sure seems as if Maruta did. And among other things, her memoir will convince you that she earned it.

I am always enriched by what you choose to cover, and by your singular writing on topics musical and beyond. Thank you!

Yeah, because the child of Latvian intellectuals as a refugee is exactly the same as infinity Somalians and 80 IQ Squatemalans. This, my friends, THIS is the mind of the modern Progressive for whom all humans are fungible widgets.

"But in a moment when immigration is under attack by the nearest thing to a fascist government this nation has ever seen"

Lol!! Good old Bob, never, ever does he fail to land on the most hysterical, bed-wetting view of politics. It's literal derangement. He's not well in the head and never has been. Oh well.