A Few Words In Praise of Randy Newman

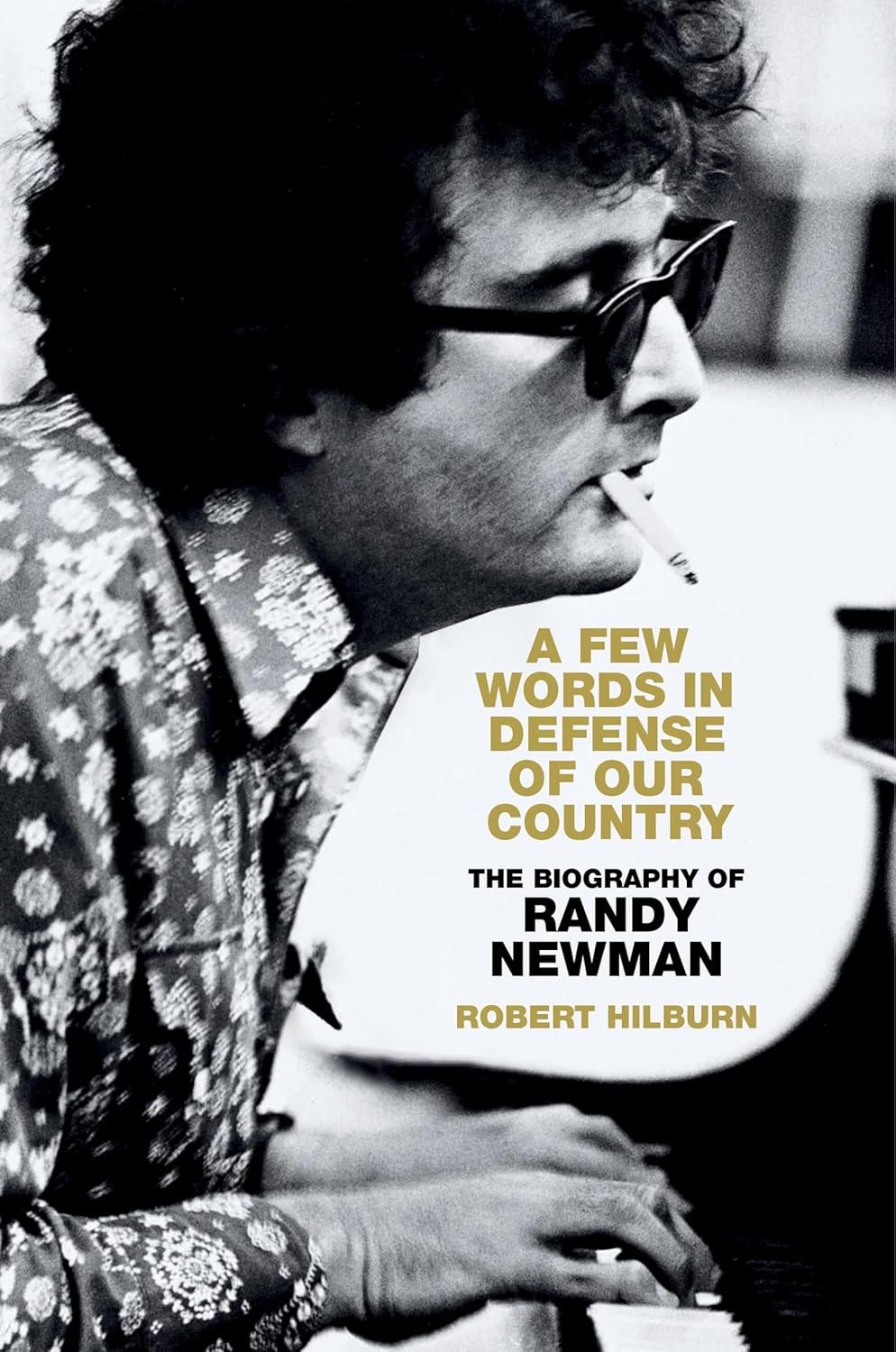

Robert Hilburn, "A Few Words in Defense of Our Country: The Biography of Randy Newman" (2024, 544 pp.)

From his Los Angeles Times stronghold, Robert Hilburn spent 35 years as one of America’s most prominent rock critics, and since his 2005 retirement has kept at it with the first-rate collection Cornflakes With John Lennon and four biographies. Of the first three of these I admired the far-reaching and thorough Johnny Cash while never getting around to the Paul Simon and assuming the Springsteen has been outflanked. But I opened his 455-page A Few Words in Defense of Our Country: The Biography of Randy Newman as soon as it arrived in the mail, and not just to see how well the graf Hilburn asked me to chip in came out. I craved the facts and insights I hoped and believed Hilburn would provide, and I wasn’t disappointed.

Unlike Cash, Simon, and Springsteen, Newman is an Angeleno, long may they survive (his roots are in Pacific Palisades itself). And crucially, he’s also the scion of what in L.A. terms is a matchless musical family—three of his uncles were major soundtrack composers, with Alfred Newman winning nine Oscars and nominated for, wow, 45. Hilburn quickly establishes not just how deep the roots of this family tree are, but how sturdily they underpin his social and business connections, even tracking a friendship going back to first grade with biz kid Lenny Waronker, who ended up running Warner Records as well as producing or co-producing all but three of Newman’s 12 studio albums. As boys the two were even deeper into baseball than music, which as Hilburn makes clear typifies how Newman’s mind works. Sure music is deeply ingrained and always there. But immersed in it though he is, he’s also a cultural sponge, a voracious reader and television addict as well as a sports fan. Thus he’s always been among other things his own species of protest singer, far broader both musically and intellectually than the leftwing guitar strummers who pioneered that term but much more ironic, unafraid to risk what is crudely called political incorrectness. Thus the title Hilburn arrived at for his biography, lifted from a track on Newman’s 2008 Harps and Angels, one of just two 21st-century albums-as-albums (as opposed to 2016’s odds-and-ends/greatest moments comp The Randy Newman Songbook Vol. 3), the other being 2017’s foolishly underrated or just ignored Dark Matter, top 10 for me that year and 13th in Rolling Stone but not even top 50 at Pitchfork or NPR.

I cite these slights because like Hilburn I have no doubt that Newman has proven himself at least as major an artist as self-evident titans Cash, Springsteen, and Simon. Who cares except maybe him that his record sales will never come close to matching theirs—he’s too brainy and also too funny, hence not earnest enough to muster their sales numbers as the radical, racially aware, small-D democrat his fans treasure. Artists along those lines are supposed to be earnest, not sarcastic. And that’s not to mention the cerebral valence of his musicality, which combines his august family traditions with the raw and often Southern-tinged rock and roll of his youth and does something that verges on impolite with the combination. From my vantage that’s at least as hard as winning a soundtrack Oscar, although maybe not nine of them, which as it happens is exactly how many Randy has been nominated for without going home with a statuette, although he has garnered two of the things for Best Original Song—2001’s “If I Didn’t Have You” from Monsters Inc. and 2010’s “We Belong Together” from Toy Story 3.

Hilburn understands all this. The text leaves little doubt that it’s what inspired him to buckle down to a 500-page biography even more socially conscious than the Cash, which is plenty political but in a much different way—Cash came from poverty, while Newman didn’t and is more a full-fledged intellectual as a result. Yet at the same time he remains very much a product of his artistic heritage—those nine soundtrack Oscars he didn’t win didn’t fail to materialize out of thin air, because in the end he seems to have found songwriting so arduous that he pursued the family business just to return to the Hollywood verities and give himself a break. Hilburn never suggests that he found that easy either. But it’s striking nonetheless that where as a songwriter he has no peer much less true rival—nobody I can bring to mind does anything more than vaguely similar—the more technical process of scoring a movie is a resort he can count on. And being the thorough biographer he is, Hilburn devotes a lot of the book to that aspect of his lifework—accurately and thoroughly I assume, but not terribly enlightening to a guy like me who’s adored Newman’s songwriting since 1970, when he gave 12 Songs an A plus up with Layla, Moondance, and After the Gold Rush. Soundtracks: auxiliary. A plus albums: gold.

Like me, Newman is now past 80, and whether he’ll ever release another album of songs, A plus or not, is a miracle waiting to happen that remains to be seen—and even more so, heard. But just in case he does, I thought I would share with you the three grafs I contributed to Hilburn’s bio:

Reluctant though I am to name names, I gotta, so 10 seemed like a nice round number. Forgive me, and forgive me as well for camouflaging more marginal judgments in alphabetical order. Ahem: Bob Dylan, Eminem, Aretha Franklin, Jay-Z, Joni Mitchell, Van Morrison, the Rolling Stones, Paul Simon, Kanye West, Stevie Wonder. All of these are acknowledged popular music titans who achieved preeminence by releasing long series of excellent albums, generally half a dozen or more, and over several decades to boot—which series were eventually interrupted by inferior albums. (To be clear, I don’t believe the Beatles ever made a bad album. Their solo members, however, definitely did. Also, I agree that Eminem is a close call, and hereby postpone all arguments in re the Taylor Swift Exception until 2026, when she’s put in her full two decades.)

Why am I inserting this parlor game into a Randy Newman biography? you ask. Simple. Randy Newman has never made even a mediocre album. NEVER! He certainly had bad days because everybody does, and he probably had bad patches because that happens too. But he never truly faltered—sooner or later the new ideas always came. So listening back with tremendous pleasure to Little Criminals (1977), Born Again (1979), and Land of Dreams (1988), the only Newman albums I've graded a mere B plus, a benchmark almost all of my 10 titans have slipped beneath, I concluded that most would probably now be A’s in any case, as would 1968’s never-rated eponymous debut, which I gave a qualified rave back then while noting nervously that his singing voice, which sounds almost boyish in retrospect, combined a “grumpy mumble” with a “deliberate drawl.” Equally important is that I’m a big admirer of 1995’s unnecessarily controversial Faust as well as Newman’s only solo albums of this millennium: 2008’s Harps and Angels, where “A Few Words in Defense of Our Country” vies with James McMurtry’s “We Can’t Make It Here” as the greatest protest song of this dire century, and 2017’s eccentric, playlet-loaded, surface-mean, stealth-compassionate Dark Matter, which with rockcrit demographics trending ever younger made few top 10s or indeed 40s when it was released but stands as my number one album of Trumpdom’s inaugural year. Five more years have passed as I write. I’d love for Randy Newman to release another album, hopefully featuring his tribute to his very own “Venus in sweatpants,” “Stay Away.” And as his contemporary I believe he’s got that album in him. But I know damn well he’s not going to let us hear it until he’s convinced he’s got it exactly right.

One of my favorite concerts was an outdoor summer performance by Newman at a local zoo 20-plus years ago. My wife and I attended and noticed there were quite a few families with kids - presumably to hear his Pixar songs. Newman played to that crowd, but also to us middle-aged misanthropes. So we heard "You Got a Friend in Me" and "In Germany Before the War" in close proximity. He was in great form, even if he seemed a little inebriated and didn't shy away from profanity during his between-song banter. Of course, he didn't play "Old Man" but did gripe about a recent argument he had with his dad.

Still think Good Old Boys is a titanic achievement that took colossal guts to put out. And the only singer/songwriter in his league aesthetically and thematically is, to my ears and brain, Nellie McKay.