A Compelling Document of Sheer Goodness

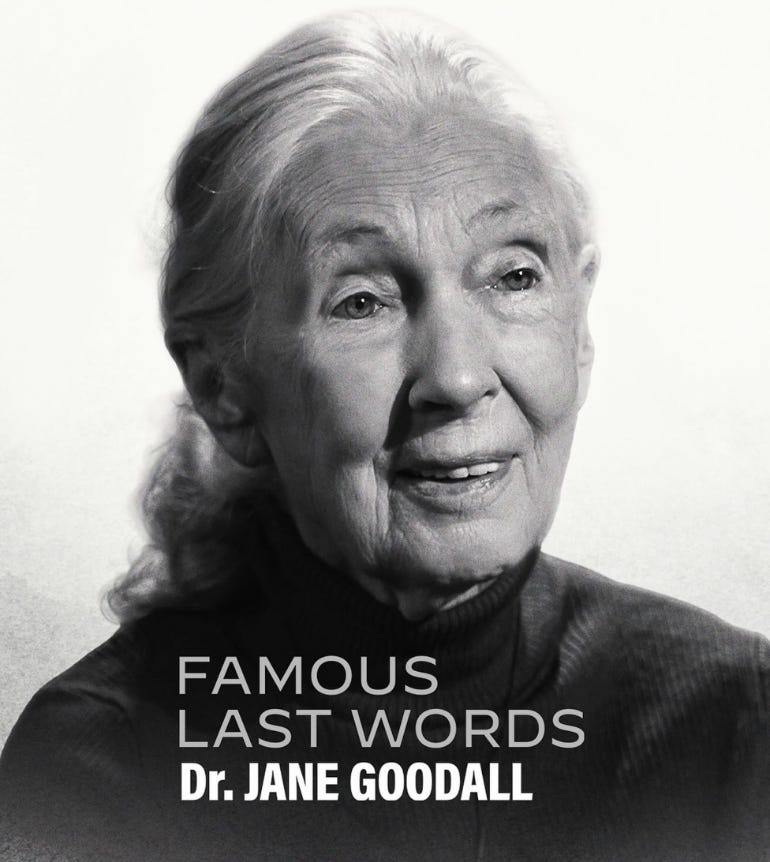

'Famous Last Words: Dr.Jane Goodall' (2025)

A few weeks ago, punching our remote with an eye to remaining conscious until our bedtime, Carola and I came upon a documentary about the renowned albeit oddly Nobel-less anthropologist Jane Goodall, best known for her lifetime of work with the chimpanzees she came to know so intimately. She had just died at 91 in Tanzania, where the London-born UN Messenger of Peace had long made her home. Seemed interesting, so we gave it a shot, and spent the next hour sitting on the couch with our mouths open.

The model was a show devised in Denmark, where its title translates as The Last Word. Here it’s called something catchier, reprising and making something more literal and specific of a witty old cliche: Famous Last Words. The idea is to interrogate—politely, one would assume, since there’d be nothing to stop the interviewee from going mum or walking off the set—a public figure so advanced in years that he or she seems likely to be gone from this planet all too soon. As the subject converses in the absence of anyone but the interlocutor, there’s a built-in promise that what she or he says won’t be made public until the interviewee dies, thus freeing the subject to be totally candid, unobliged to bat down objections or explain, qualify, or elaborate ideas, observations, or generalizations that might have unanticipated holes in them. You needn’t be cautious. You don’t have to watch your back. You can let it all hang out.

As Carola and I sat back to watch and hear producer Brad Falchuk—whose previous credits include Glee, Scream Queens, and American Horror Story, whatever they are, but whose questions are pertinent and uninvasive—get the show rolling, we were struck immediately by Goodall’s affect. Before our eyes sat somebody’s slender, genteel, calm, unmistakably intelligent grandma not holding forth so much as simply chatting with us about things that matter to her as she takes a very occasional sip of whiskey. Without being in the least forceful much less polemical about it, for instance, Goodall assumes that we all share political ground—our dismay with Trump is taken for granted, and although she muses briefly about checking out the universe from one of Elon Musk’s spaceships, she doesn’t seem to like him much either. Not that she emerges as any sort of solitary much less eccentric much less misanthrope. Quite the opposite. Her two marriages and a love affair she’s decided it would be evasive to omit are discussed briefly but candidly. She has much less desire to revisit these two ex-husbands in the afterlife than two chimps she was very fond of. But she also feels, persuasively, that she was put on earth to befriend and understand all the chimpanzees she not just admires but loves, and here if possible to both recognize a divinity she believes is out there and convince the world to outgrow the scourge of plastic bags. Without anything resembling vanity she’s matter-of-fact about being recognized at airports by strangers, some of whom ask if they can touch her. She was born with a purpose it is her duty, her fate, and her abiding pleasure and privilege to do all she can to make the most of. And the reason Carola and I watched mostly in silence with our mouthes open was that we found ourselves something like awestruck at this compelling document of the kind of sheer goodness few of us ever get to so much as glimpse.

Good flick.